The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

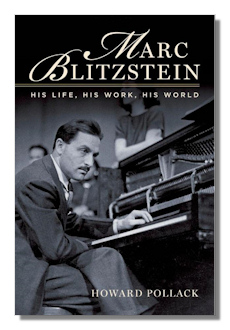

Marc Blitzstein

His Life, His Work, His World

Howard Pollack

Oxford University Press, 2012. 618 pages

Illustrations, extensive notes and index

ISBN-10: 0199791597

ISBN-13: 978-0199791590 (alkaline paper)

Summary for the Busy Executive: It's about time.

Howard Pollack has gotten into the groove of writing standard studies of American composers with wonderful books on John Alden Carpenter, Walter Piston and the Harvard composers, Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, and now Marc Blitzstein. Blitzstein's formerly bright star has faded almost to black. He lives primarily as by far the best translator of Weill and Brecht's Dreigroschenoper (Threepenny Opera), but hardly anyone plays his music. Major works go either unrecorded or recorded in mutilated form.

A staunch left-wing composer during the Thirties and Forties, Blitzstein dedicated his art to social change, with an acute awareness of American class frictions and racism. As a mature composer, he composed almost exclusively dramatic music – for plays, radio drama, films, and theater. Most of them have texts, the majority written by Blitzstein himself. Some argue that this has made his scores too specific to the times they depict, as in the exhortation in the "Airborne" Symphony, written during (and slightly after) World War II, to "open up that Second Front." I would counter that Blitzstein was less a political composer than a moral prophet like Jeremiah. What he writes still has relevance because things like greed and war, as well as loyalty, sympathy, and heroism haven't left us. The Cradle Will Rock may on the surface concern workers trying to organize a union in a town dominated by a greedy capitalist not above resorting to bribery, intimidation, and murder. After aLL, such conditions still exist, but even if they didn't, the resistance of the weak against corrupt authority, I'm afraid, will always be with us, although its specific guise may change. Objecting to Blitzstein on such grounds is like dismissing Turandot because the Chinese imperial dynasty's no longer around.

I would also contend that in addition to its aesthetic importance, Blitzstein's music represents an important link in the development of an American style based on strong vernacular elements. Ned Rorem, for example, claims that Bernstein's idiom owes much to Blitzstein. Frank Loesser, composer of Guys and Dolls and Most Happy Fella used to attend Blitzstein's shows several times, saying he was "going to school." While Blitzstein may not have directly influenced Stephen Sondheim, he, Kurt Weill, and, later, Leonard Bernstein provided strong models of highly-trained composers turning out Broadway works of great musical sophistication.

The details of Blitzstein's life, unlike those of many composers, attract interest all by themselves. For more, I recommend you read Jim Tobin's review. Pollack makes use of previous sources and interviews with those in Blitzstein's circle (close friends and colleagues Mordecai and Irma Bauman, for example). Some of this was 11th-hour rescue work, since most of the interviewees are well past their threescore year and ten. Pollack has also relied upon Eric A. Gordon's Blitzstein biography Mark the Music, and Gordon also generously shared his research. Gordon, however, is an historian, not a musician. His excellent depiction of the New York left-wing musical scene from the Thirties through the Fifties was also a pioneering effort. However, he admitted that he didn't feel up to the task of focusing on Blitzstein's music. No such problems with Pollack. Gordon also presented a picture of Blitzstein as a composer blocked by Blitzstein the librettist, who refused to collaborate with others. Pollack corrects this notion to some extent, by pointing out Blitzstein's collaborations. Blitzstein, however, often took a long time to finish things due to snarls in his libretti. The "Airborne" Symphony, for example, begun during World War II, finally appeared in 1946. However, it wasn't as if Blitzstein ran dry. He finished other works in the meantime. In fact, the size of Blitzstein's catalogue surprised me, given the impression left by Gordon's account.

Pollack writes readable, accessible prose. There's no musical type to contend with, and he still manages to say valuable things about the music. His study also seeks to champion Blitzstein's work, to afford it its due place in American music, and to this end, he dissects and rebuts the adverse criticism. As for me, I'm on Blitzstein's side. I believe him a composer caught in old-fashioned, even quaint attitudes from the critics, so I cheered Pollack on.

As I read, I came across a passage on the "Airborne" which gobsmacked me. Pollack used a small quote from my review of the Bernstein stereo recording (Sony 61849). I immediately went to the index and, sure enough, I found my name. So you can now say you know me. Lucky you.

Copyright © 2013 by Steve Schwartz.