The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

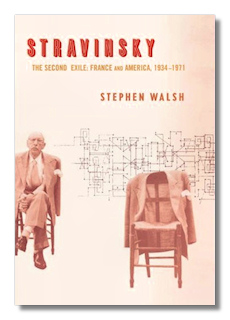

Stravinsky: The Second Exile

France and America, 1934-1971

Stephen Walsh

Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2006.

ISBN-10: 0520256158

ISBN-13: 9780520256156

Summary for the Busy Executive: Leaving home.

The second volume of a two-volume biography, Stravinsky – The Second Exile: France and America documents the composer's life and career from shortly before the move to the United States to his death in New York. When you think of it, Walsh's two volumes documents the two major changes in Stravinsky's artistic development: the first volume, from the Russian "barbarism" of Firebird, Pétrouchka, and The Rite of Spring to the neoclassicism of Pulcinella and Oedipus Rex; in the second, from the neoclassicism of the Concerto for two solo pianos to the serialism of Threni.Walsh concentrates on life and career. I normally hate this type of bio of an artist. Most composers lead pretty dull lives. If you were to make a truthful movie of one, you'd have long stretches of Our Hero scratching on a piece of paper or staring off into space or checking the want ads for temp jobs. In other words, it's not the life itself that's interesting, but the work that life produced. Of course Stravinsky's life lacks the excitement of Rite of Spring or Oedipus Rex or Agon. I can't think of any life that measures up. Ultimately, one's interest in most composers biographies depends largely on the interest in the music. But Stravinsky was a more interesting personality than most, especially in light of the music he produced and the contradictory things he said about it. Without quite uncovering the mystery of genius, Walsh nevertheless manages to keep our attention and build suspense, mostly through offering shrewd guesses into the composer's character and how that affected the course of his life. I happen to love almost everything Stravinsky wrote, so naturally I'm interested in the man. However, Stravinsky's family and personal relations are so tangled that I'm confident this book would appeal to those who can leave the work alone. Even with his biographical emphasis, however, Walsh provides valuable "bird's-eye" insights into several major scores – lagniappe, as it were.

Early on, Stravinsky was shrewd enough to realize that he could not reasonably expect to make a living through composition alone – even scores universally recognized as groundbreaking – especially considering the glacial pace at which he wrote. He more than once wished aloud that he could write interesting music at Mozart's speed. He also developed a taste for high living. Conducting and performing provided most of his income for many years. He was also one of the first twentieth-century artists to realize that his celebrity also had cash value, and he assiduously applied himself to cultivating his image as Artistic Leader and Philosopher. The image stood at some odds with the composer himself. Far from the intellectual "composing automaton," he depended far more on instinct, experience, and inspiration than he cared to admit. Every one of his major aesthetic statements was written by someone else – sometimes with at least some participation on his part, sometimes not. He disliked analyzing scores, beyond what his incredible ear could pick out on the fly. However, the demands of celebrity increased his skills of self-promotion and enhanced the value of his name and his brand. His celebrity saved him at least twice.

Stravinsky subjected himself to punishing tours, even in old age, partly for the money and partly because he enjoyed traveling and especially sightseeing. More than any other quality, his rootlessness comes through. The most important word in Walsh's title is undoubtedly "exile," and of course the family was forced to flee twice, once from Russia, once from France. The second time, Stravinsky had to rebuild his career in the United States, whose language he didn't know (to the end of his days, he spoke a very idiosyncratic English) and whose interest in his music was slight. For years, Stravinsky had to scramble for commissions – usually for lighter work – and conducting gigs. His celebrity kept him afloat. Royalties were held back not only because of the war, but because his three most popular scores were under Russian copyright, which had no force in the West. He appeared in a magazine ad for a record player. Disney used a drastic rewrite of The Rite of Spring for his visionary Fantasia and paid Stravinsky for the privilege, although he wasn't legally bound to do so. Stravinsky lived in Los Angeles, but no movie studio ever commissioned an original score, although producers were happy to drop the rumor that he was being "considered" for this or that film. To be fair, when one considers the film sketches that found their way into other pieces (music for The Song of Bernadette turned up in the second movement of the Symphony in Three Movements), Stravinsky's music would have fit in badly with the Romantic style of Hollywood filmmaking. Woody Herman commissioned the Ebony Concerto; Billy Rose, the Circus Polka. Both show wit and verve, but compared to even the recent Symphony in C, completed in Europe, hardly taxed the composer's powers.

The Stravinskys never felt at home anywhere outside Russia – not in Switzerland, not in France, not in Los Angeles, not in New York. Yet Russia was impossible. Vera, the composer's second wife, would have loved to have lived in Paris, but that city was not hospitable to Stravinsky's music, especially after World War II. Furthermore, as his infirmities increased, he needed a first-class medical city like New York, where they finally settled. Wherever they lived, they kept their Russian friends-in-exile close, maintaining a bit of Russia around them. Stravinsky's funeral poignantly underscored his exile. He was buried, not in Paris, Los Angeles, or New York, but in Venice, a city he never lived in but which had seen the premieres of five major works.

The main supporting player of Stravinsky's American residence is, of course, Robert Craft. To say the least, an ambiguous figure, Craft has received his share of brickbats. He first turned up in Stravinsky's life as a young conducting student at Juilliard and a fan. With a strong interest in cutting-edge modern music, Craft was an odd duck at the Juilliard of the time, far more conservative than it is now. He arranged a Stravinsky festival in New York, and afterwards the composer asked him (as he had asked friends and acquaintances throughout his career) to smooth his concertizing on the East Coast. Unlike many of Stravinsky's friends, Craft actually showed competence. The composer came to rely on him more and more, to the point where Craft became Stravinsky's musical factotum. He rehearsed orchestras so that the aging composer wouldn't tire. He became a mentor to the composer in English-language culture and the last and most extensively-employed of the composer's "ghosts." Craft also introduced Stravinsky to the music of the Second Viennese School – Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. Critics have accused him of parasitically leeching onto Stravinsky to further his own conducting career and leading him down the treacherous path of dodecaphony. The composer's children saw him as a thief trying to steal their inheritance. One can put down much of this to professional spite, to feelings of partisan betrayal, and to the inevitable splits among family and quasi-family that occur when a wealthy and domineering parent dies. For Stravinsky indeed dominated his children, well into their middle age. A Victorian paterfamilias (and, of course, an adulterer), he kept them dependent on his largesse, demanding their undiminished fealty and upbraiding them as ungrateful whenever they attempted to show some independence. By the end, he had alienated them all, to the point where they had nothing left of him but their inheritance. Nevertheless, he needed family as a stabilizing force and lost for himself what he needed from his children. It should surprise nobody that he became more strongly attached to Craft.

However, the charges against Craft become more believable in the matter of the historical accuracy of his accounts (even those which credit Stravinsky's collaboration) of the composer's opinions, life, and death. Several writers, including Walsh, have picked apart Craft's narrative and found it wanting. One can never be sure whether the opinions Craft "reports" actually came from the composer. But, of course, Craft isn't alone. All of Stravinsky's literary collaborators have made stuff up, and Stravinsky, surprisingly diffident about his philosophical skills, acquiesced and even encouraged them, for the sake of a speaking fee or enhancing his celebrity and prestige among intellectuals and academics.

A fine historian, Walsh scrupulously separates fact from the notoriously wishful thinking of Craft's narratives. Walsh isn't interested in bashing Craft and in several places vigorously defends him against the charges of careerism and Svengali-ism. After all, Craft's identification as Stravinsky's errand-boy did his independent conducting career little good, especially after the composer's death. He was increasingly perceived as a man who couldn't get a gig on his own – a slur against his competence, as many of his recordings attest, manifestly unfair. Furthermore, Craft himself recognized this early on. However, he became attached to Stravinsky and Vera. He knew how much they relied on him, and he couldn't abandon what he considered his duty or betray his genuine love for them. On the other hand, Walsh doesn't overlook Craft's flaws – temperament, imperiousness, snobbery, paranoia (although, as the old joke goes, even paranoids have real enemies), sexual promiscuity, and an emotional over-investment in his role as the composer's advocate. The latter has led him at times to insert himself into events he probably was never at. His claim that the composer died holding his hand, for example, conflicts with contemporary testimony of the secretary and eyewitness, Lillian Libman, who asserts that the composer was already positively dead by the time Craft came into the room. Furthermore, Craft's account doesn't surface until years afterward. Craft seems to have increasingly seen himself as the composer's spiritual son, closer to the composer than Stravinsky's own children and grandchildren. In the last, he may very well have been right.

Beyond question (and for me of the greatest importance), Craft guided Stravinsky to a creative renaissance, the dodecaphonic serialism of his final period. Craft's detractors have always claimed that he led the composer astray. I agree with Craft himself, to the effect that "no one could lead that horse to water, let alone make him drink." The choice was Stravinsky's. It's too early in their relationship to posit a Svengali relationship between a recent conservatory graduate and one of the two greatest living composers. Stravinsky was always interested in "constructivist" techniques. However, his neoclassicism – never particularly popular with either the critics, the public, or the avant-garde – began to seem played-out to Stravinsky himself, although he continued to work largely within the style. However, in the Forties, he began to experiment with tonal "rows" of however many notes he wanted – 11, 13, whatever – in works like the Sonata for Two Pianos and the graveyard scene of The Rake's Progress. Dodecaphony represented a possible way to renew his music. Nevertheless, while he respected Schoenberg, once Craft helped him figure out what was going on, there remained plenty in the music that he disliked or found unsympathetic and alien. Chief was probably the rhythm and phrasing, Schoenberg too close to post-Wagnerian habits, which Stravinsky had never cottoned to. Stravinsky created his own dodecaphonic music, which sounded little like the Second Viennese School and more like what he had recently written. For one thing, it danced. Of the three founders, Stravinsky probably felt closest to Webern, finding similarities in that music to his love of ritual and intense meditation, such as we find in his Mass. We owe Stravinsky's turn to serialism, his creative rejuvenation, to Craft. Thus, we owe the final masterpieces of the Septet, Canticum Sacrum, Agon, Threni, "The dove descending," and the Requiem Canticles in some part to Craft.

Walsh tends to see neither gods nor demons, but people. He also has the gift of tying often-mundane facts into a compelling story and of bright, elegant prose. I can't praise this book (and its predecessor) highly enough.

Copyright © 2009, Steve Schwartz.