The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

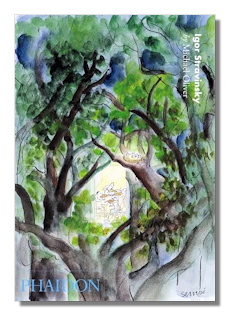

First published in 1995, this title is part of Phaidon's 20th Century Composers series. According to publisher, the series "presents authoritative and engaging biographies of the great creative musicians of our time, augmented by striking visual material and essential reference information." Igor Stravinsky generally fits that description.

Michael Oliver (1937-2002) worked on documentaries and magazine programs about music for BBC Radio 3 and reviewed for Gramophone. His prose is clear and often elegant in a way that reminds me a little of the music from Stravinsky's neoclassical period. I mean that as a compliment, though his habit of running several clauses together will have you rereading a sentence here and there. Given the obvious limits on length, he concentrates more on Stravinsky's music than on his daily life. You won't learn of Ravel's visits to Stravinsky's apartment in Clarens, Switzerland when Stravinsky was writing Rite of Spring, his fallout with Ernest Ansermet, or much about his efforts to recoup profits from early works by revising decades later, etc. You will get a fine, straightforward account of the composer's life and a perceptive look into his music.

Oliver does point out some key and perhaps unfamiliar aspects of his subject's life. Stravinsky's devotion to St. Petersburg until the end of his life might surprise people who thought the composer and long put Russia into his past. The account of Stravinsky's childhood turns up the charming tale of the young boy who tries to imitate tunes on the piano, mistakenly inserts some wrong notes, and claims it "already made me a composer." Among the few bits of gossip that do come through are Stravinsky's two marriages, the first to Catherine who was ill for many years before his death and then to dancer Vera Sudeikina, with whom he had an affair while Catherine was alive. Oliver makes no judgment, but he does point out the resulting ill feelings with his mother and children, the latter causing some serious problems after his death.

It was interesting to learn that Stravinsky's long – and necessarily profitable – conducting career began as the result of a failed Serge Koussevitzky-led performance of Symphonies for Wind Instruments. Determined to avoid a recurrence, he conducted his Octet on the huge stage of the Paris opera. I have always like his clever harmonization of 'The Star Spangled Banner', but I had no idea he hoped it would become the standard version of the American national anthem. Nor was I aware that Circus Polka was written for a parade of elephants a the Barnum and Bailey Circus. Stravinsky was never known as a film composer, though the Symphony in Three movements famously contains remnants of an attempt to score The Song of Bernadette (a project that went to Alfred Newman). I had no idea that he was considered for the score of Jane Eyre that eventually went to Bernard Herrmann.

It is interesting to note some of Stravinsky's work that Oliver finds especially important. He finds Oedipus Rex symbolic of his renewed religious faith and the high point of his "white drama" style that included Apollo and Orpheus. He considers Agon, a work many find difficult, to be his exuberant breakthrough into the new world of serialism. Oddly, he barely mentions the Violin Concerto and a number of other works, I expected to read about. We learn of his disdain for Berlioz, his difficulties with Benjamin Britten, and his near reverence for Anton Webern.

Oliver does a good job of describing Stravinsky's life in Los Angeles – better than his treatment of the composer's life in Europe. His brief account will interest devotees of the other exiles living there at the time – Schoenberg, Klemperer, Artur Rubenstein, and many members of Hollywood's elite.

The book is exceptionally good with Stravinsky's later works. Some may find this to be at the expense of the more famous early ballets, but that very fame clearly gave Oliver license to spend more time with lesser known pieces. Many critics dismiss Stravinsky's serial pieces, but Oliver clearly appreciates them and he does a fine job of describing them. In fact, this is as good an introduction to serial music in general for the layman that I've seen.

Igor Stravinsky is a short book that necessarily skims on many details (but brings out a host of others). It is a snapshot, but a clear one that leaves me feeling I had lived with the composer for a brief while. Stravinsky comes of as a man secure with his music, but always just a bit anxious out of his native Russia. He spoke French well, but the English he needed in America was more difficult. Stravinsky's relationship with Robert Craft is probably accurately portrayed as like father and son: I find it interesting that a composer of Stravinsky's reputation so easily accepted guidance and help from a musician so much younger. Stravinsky's reputation as pecunious is well earned, but Oliver makes it almost appealing when he associates with the composer's early travails and the fact that Stravinsky was never an extremely wealthy man – one reason he was conducting almost to the end of his life and past when he quit composing.

The many illustrations are well chosen and placed in a way that often illustrates something or someone the text is discussing. Some are quite compelling: Stravinsky with a young Ravel, with his mother, several with Jean Cocteau, etc. There is even one of Sunset Boulevard, near where the composer lived at the time. Also included are several sketches used to create ballet costumes, and a number of scenes from productions. All are in black and white. For many, color would be beautiful, but add color, and the book no longer costs $15.

Appendices include useful list of works and a good annotated bibliography. The list of recommended recordings includes only one performance per piece. That's far too limited for a composer like Stravinsky.

Copyright © 2008 by Roger Hecht.