The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

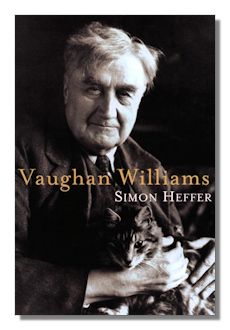

Vaughan Williams

Simon Heffer

Boston: Northeastern University Press. 2000

Hardcover. 167 pages.

ISBN-10: 1555534724

ISBN-13: 978-1555534721

Summary for the Busy Executive: Save me from my friends.

Simon Heffer has written this book for the general reader. A British political journalist, he has either little or no musical training, but he is what we used to call an Intelligent Listener. He knows Ralph Vaughan Williams's music. At 167 pages, this can't provide anything more than a general introduction. Indeed, it reads a little like an expanded encyclopedia article.

The book suffers from Heffer's artistic judgments. Perhaps he has lived too much in the British critical atmosphere to do more than repeat old notions. When I came upon Heffer's description of the American poet Walt Whitman as "ordinary" my mind blurted, "Uh-oh." It's not that Heffer writes to tear the composer down – quite the opposite, in fact. However, he does perpetuate the myth of Vaughan Williams's clumsy technique, especially in orchestration. How anyone can listen to the London Symphony, Tallis Fantasia, Concerto Grosso, Concerto Accademico, Romance for Harmonica, or Flos Campi, among many other scores, and find them "clumsy and amateurish" defies my understanding. There are heavily-scored passages in some Vaughan Williams works, but the expression justifies them. Unfortunately, Heffer apparently hasn't the tools to zero in on his dissatisfactions.

Heffer can't get over the fact that Vaughan Williams doesn't sound like his friend, Gustav Holst and emphasizes how much help Holst gave him. He doesn't, however, say much about the help Vaughan Williams gave Holst. In fact, both men exchanged works in progress for criticism and suggestions.

Heffer also comes up with conclusions that sound like repetitions of the first reviews. The comic opera The Poisoned Kiss comes in for its usual lambasting due to its weak libretto. I agree about the libretto, a bad attempt (by a VW relative) to resurrect W. S. Gilbert's "topsy-turvydom." But … but … but … glorious tunes carry the enterprise forward. The same problem to a lesser extent also dogs the Four Songs by Fredegond Shove (more VW kin). Yet, Heffer can't explain why the songs, despite their texts, are among the finest in the repertory. Besides, as Schubert and Brahms proved again and again, a great song needn't have great texts. Heffer gives most of the work of the Fifties short shrift (with the welcome exception of the Ninth Symphony), considering it a rehash of earlier work. The "morality" Pilgrim's Progress comes in for this brickbat. Of course, its long gestation (about forty years) practically guaranteed echoes of earlier scores, especially the Fifth Symphony. But I'd argue that the composer turns his ideas to different expressive purposes and indeed most of those echoes receive their fullest expression in Pilgrim. To me, it's the grand summing up of VW's art, and as the years pass, the echoes of previous work matter less and less, because "previous" itself ceases to matter to most listeners.

All in all, the only thing this book saves you is time. There's almost nothing you won't find in either Michael Kennedy's Life and Works or in Ursula Vaughan Williams's R. V. W., and those books contain way more nourishment.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.