The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

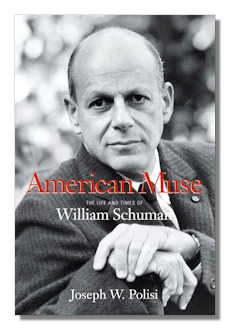

American Muse

The Life and Times of William Schuman

Joseph W. Polisi

New York: Amadeus Press. 2008. 595 pages.

ISBN-10: 1574671731

ISBN-13: 978-1574671731

Summary for the Busy Executive: If only the Muse had visited.

At one time, you could have argued for William Schuman as the most powerful man in American classical music – first, as head of Juilliard and reformer of musicians' training in the U.S.; second, as the first president of Lincoln Center. Indeed, this administrative career overshadowed Schuman's real vocation, composer. After the first generation of Harris, Thomson, Piston, and Copland, he and Samuel Barber probably stood out as the most prominent representatives of the second.

Though shunning dodecaphony, Schuman nevertheless wrote "hard" music. He received criticism from writers who deemed him "deficient in melody," but mainly because they had rather old-fashioned notions of tune. Besides, not everybody can be Vaughan Williams or Gershwin. Schuman grabs a listener through his vital (even sexy) rhythms, his idiosyncratic orchestration, and his sense of inexorable development. However, he has few hits. When the Kennedy Center honored him (along with Claudette Colbert, among others), I kept wondering what in the hell they would play. Indeed, in the book Schuman, well aware of his problems connecting with the kind of people who watch the Kennedy Center Honors, recounts an amusing story about that very thing. They finally decided on the final movement of (predictably) the New England Triptych.

Nevertheless, I can remember a time when I and the other classical-music geeks at my high school had Schuman's Third and Fifth Symphonies on our collective Hit Parade, along with Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, Vaughan Williams's Tallis Fantasia, Ginastera's Estancia, and the Copland and Stravinsky ballets. While our classmates went cruisin' for burgers and girls, we spent our Fridays and Saturdays at one another's houses to listen to the Verdi Requiem or the Barber Piano Concerto – a thoroughly misspent youth, although I managed to catch up on burgers and girls in college. The point is, I guess, we were music-mad and curious about names we had never heard before, always hoping for the same electrifying thrill we got when we first heard The Rite of Spring. Schuman provided his share, thanks to champions like Ormandy, Bernstein, Gregg Smith, and Frederick Fennell. I kept up with Schuman, abetted by raves from my favorite music critic, Andrew Porter in The New Yorker. One could argue for his cycle of eight symphonies ("eccentrically labeled 3 through 10," according to the composer) among the finest of the century. Indeed, the book title, "American Muse," comes from the subtitle of the Tenth. Even pieces I recognize as not among his best, I happen to like. I certainly think his music well-made and full of hard, independent thought and the closely coherent unfolding of ideas. Schuman's music has the advantage of sounding like nobody else's, and his symphonies indeed became something for wannabe composers like me to shoot for, especially the independence part.

So it was a surprise to learn from Polisi of Schuman's music (especially the late music) pooh-poohed in places like the New York Times. Schuman never seemed able to catch a break from any of the music critics in that paper. Indeed, some suggested that the only reason Schuman got played was due to his positions of power in the American musical establishment. However, prestigious organizations continued to commission him, even after he resigned from Lincoln Center, and he made a damn comfortable living from his works alone. Somebody must have liked the music. Apparently, certain people had trouble believing that the brain of an exceptional administrator could cohabit with that of an outstanding artist. Indeed, when Schuman died, a "think" piece by then chief music critic of the Times, Edward Rothstein, included this: "Had he been a greater composer, he might never have been as great an administrator." Somehow, according to Rothstein, if Schuman had been a greater composer, he would have composed more, rather than frittered away his time in non-artistic pursuits. I wonder how Rothstein felt about Charles Ives. Even a cursory look at Schuman's catalog should make one realize the sheer volume of his accomplishment. It dwarfs Copland's and Bernstein's, for example, and much of it is powerful, passionate stuff. For Schuman, composing was a solitary job, while administration expressed his gregarious, social side. He liked writing music and he liked people. He made time for both.

Furthermore, Schuman brought an artist's perspective to the organizations he headed, especially a strong belief in the intellectual mission of art. He kept running up against public-spirited businessmen who not only had opinions about matters they knew little about from the inside, but who also had accustomed themselves to watching the bottom line. They looked askance at Schuman's adage that the job of an arts organization was "to lose money wisely," although that's the only true justification for such an organization, especially in the United States. The dumbing-down of public libraries, symphony programs, theaters, and museums, schools (of course), the neglect of present-day art, are just some of the results. Education itself is rapidly becoming the mere flattering of public prejudices. At any rate, this conflict ultimately resulted in Schuman's resignation from Lincoln Center, seven years before his contract officially ended.

A fellow who writes so passionately deserves that kind of book. Polisi, a President of Juilliard himself, knew Schuman, but you'd never glean that from the prose. Schuman, by Polisi's own account, was an energetic, witty man, but he comes across here as gray. The administrative stuff is especially boring, but Schuman's initiatives and fights were exciting. It just doesn't show up in the book, buried under deadly, dull prose and bad structuring of the stories. Perhaps Ron Chernow should have handled that part of Schuman's achievement. Polisi improves by miles when he starts talking about the music, and the more specific he gets (there are ten really good descriptive analyses in the back matter), the more the interest shoots up. But it's still only half a portrait.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.