The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- C.P.E. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

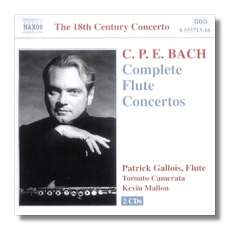

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

Complete Flute Concertos

- Flute Concerto Wq. 22

- Flute Concerto Wq. 166

- Flute Concerto Wq. 167

- Flute Concerto Wq. 168

- Flute Concerto Wq. 169

- Sonata in A minor for solo flute, Wq. 132

Patrick Gallois, flute

Toronto Camerata/Kevin Mallon

Naxos 8.555715-16 DDD 2CDs: 57:09, 68:45

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the second son of Johann Sebastian Bach and godson of Telemann, straddled the Baroque and Classical periods. When he was born in 1714, his father and Handel were at the peak of their powers. At his death in 1788, Mozart was at the peak of his. It is not surprising, then, that C. P. E. Bach's music embodies characteristics of both late Baroque and early Classical composition.

One characteristic typical of the Baroque period is musical recycling. It was not unusual for a Baroque composer - such as his father - to adapt a sinfonia from a cantata into a concerto movement, or to take a secular aria and insert it, with a new text, into a sacred work. This wasn't laziness, just pragmatism. Most of the flute concertos offered here started out as harpsichord or organ concertos; only Wq. 167, the Flute Concerto in B flat, appears originally to have been written for that instrument. (The Flute Sonata is an original work too.) Why the flute? Starting in 1738, Bach was in the service of Frederick the Great, an accomplished flutist, and was required to keep the King supplied with repertoire, as well as to accompany him on the harpsichord. No doubt his duties made it necessary for him to cut corners where he could, although it is unlikely that his contemporaries would have found anything reprehensible about such a practice.

The music is delightful, more reminiscent of Haydn than of Johann Sebastian Bach. While it is conservative, it isn't merely predictable; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was a creative composer, and each work is not only ear-pleasing but distinctive. For example, in the A-minor concerto (Wq. 166), the contrasting use of pizzicato versus arco with the same thematic material is a happy surprise, guaranteed to raise a smile. Here's a composer who both understood and accepted his role in society; a master, if not an innovator, he wrote "leisure music" par excellence.

Patrick Gallois is a major talent with an already impressive career of orchestral and solo work, and recordings, and Naxos is lucky to have secured him for these discs. Here, he plays a flute made from both African Blackwood and sterling silver. Its tone-holes are square – not the usual round-hole design. These innovations supposedly aid in articulation and tonal power. Gallois lacks in neither of these areas, and his gracious playing certainly evokes the court of King Frederick the Great. One characteristic that some might find distracting is Gallois's evident fondness for bending the pitch on long-held notes. I assume he does this for expressive purposes. Only time will tell if I become tired of this device. The Toronto Camerata plays cleanly, and in period style (but on modern instruments, I assume), and they do so with plenty of spirit. The engineering is top of the line.

Copyright © 2003, Raymond Tuttle