The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

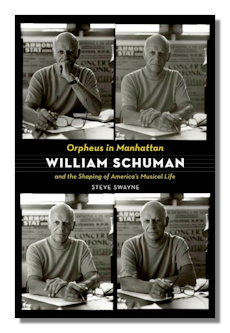

Orpheus in Manhattan

William Schuman and the Shaping of America's Musical Life

Steve Swayne

Oxford University Press, 2011. xv, 692 pages

ISBN-10: 0195388526

ISBN-13: 978-0195388527

William Schuman, one of the most accomplished and prolific American composers of the last century, enjoyed birthday celebrations. He surely would have loved the way the hundredth anniversary of his birth has been celebrated, with the publication of no fewer than three books about his music and his very public career. Last year I wrote about the substantial biography by Joseph Polisi, the President of Juilliard, where Schuman had served as a notably innovative President: American Muse, The Life and Times of William Schuman, and Walter Simmons has just published The Music of William Schuman, Vincent Persichetti, and Peter Mennin: Voices of Stone and Steel as the second in a series of books celebrating the music of underappreciated American composers. As of this writing I have yet to see Simmons' new book but Steve Swayne, toward the end of a staggeringly long list of acknowledgements at the beginning of Orpheus in Manhattan, gives special thanks to "Walter Simmons for making [him] hear and see music in new ways."

Swayne's book focuses primarily on Schuman's music. Schuman wanted to be known and remembered primarily as a composer though he never wanted to be a full-time composer. He needed other activities and he engaged in plenty of those throughout his life. More on that below. As a composer, he calculated to the hour how much time in a year he needed for this creative work (600-1000 hours), and he recorded how much time various works took him to complete. He did his best to preserve that time even during his years as an administrator. When at Juilliard he was more successful at that than when he was President of Lincoln Center.

In the course of a lengthy life Schuman managed to write a great deal of music and I think it is likely that no one knows this music better than Steve Swayne. In the course of his chronological account of Schuman's life, Swayne gives a blow by blow account, without musical examples or obscure terminology, of the origins, composition, musical characteristics, and both critical and listener reaction to seemingly everything Schuman wrote following his Tin Pan Alley years, and even some of the songs he composed then. I mean, even one-minute fanfares. Swayne shows how Schuman reused parts of works, and even whole movements, for newer works; in some cases he withdrew the earlier compositions without attempting to publish them. Schuman, especially in his later years, received far more offers of commissions than he was able to accept. Some of the ones he did accept were completed quickly but others were delivered long after the desired date. Sometimes he went many months without putting pen to the very fine manuscript sheets he was in the habit of using. When done, he wrote the dates of completion rather than using any opus numbers. A few works went through a number of permutations, notably the three versions of his Violin Concerto; New England Triptych, which began as a Chester Overture; and Amaryllis which became, among other things, the Concerto on Old English Rounds for Viola, Women's Chorus and Orchestra.

Schuman particularly liked writing for Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra but his commissions came from many quarters and he generally did not accept a commission without a substantial payment – which he occasionally returned if he felt he could not fulfill the commission to his own satisfaction. He had particular difficulty in finding suitable texts for vocal or choral works. He liked Whitman and he was particularly happy with the poem that Richard Wilbur wrote for On Freedom's Ground.

Schuman mastered counterpoint at a young age – producing vast numbers of exercises for his teacher – and employed it a great deal. He liked long lines. Sometimes he used Baroque forms, such as the fugue, passacaglia and toccata movements in his Third Symphony. Late in his career he used some serial techniques – sparingly – but was never sympathetic to the avant-garde. In his substantial efforts on behalf of other composers, such as Carter, however, he accepted the way they wrote. Composers he particularly liked included Copland, Barber and Bernstein.

Two of the five parts of his book are headed "The Juilliard Years" and "The Lincoln Center Years" but, for Schuman's administrative accomplishments and struggles there and at Schirmer, Polisi's account is more full and more dramatic, if sometimes so detailed as to seem repetitious, notably Schuman's reiterations of his vision for Lincoln Center in contrast to the fiscal primacy of its Board of Directors. Swayne writes smoothly and well, but I found that Polisi's biography also gave a fuller account of Schuman's life with his wife and children than Swayne gives. (For instance, if I may be permitted a personal note, I learned from Polisi that Schuman brought his children to the same park on Sundays where my own father brought me and my siblings.) Both books touch on Schuman's political inclinations at different times, with different emphases. Schuman comes alive as a person, for me, more in Polisi's account than in Swayne's. For instance, Polisi shows what an accomplished and persuasive speaker and writer Schuman was; this was a key to his career success. Swayne, for his part, relates how powerfully persuasive Martha Graham could be – with her eyes – so he might well have done something like this for Schuman. It seems, though, that Swayne may have made a choice not to go over ground well covered by Polisi; he explicitly refers to Polisi's account of Schuman's final days and death as providing the particulars.

A biographical matter that Swayne has turned up for the first time, I believe, was that the well-known story of Schuman suddenly discovering classical music at a Carnegie Hall concert and then immediately withdrawing from college and enrolling in a music program is quite a lot foreshortened from the actual course of events which was rather longer drawn out. We learn also that, subsequent to that first Carnegie Hall experience, Schuman practically haunted the place, attending several concerts a week.

A biographical matter that Swayne spends a disappointingly little space on is Schuman's studies with Roy Harris. Disappointing, because it is commonly said of Schuman that his style grew out of Harris's. There is a hint of rivalry or jealousy, when Schuman became successful but nothing like the very full account that Swayne provides about so much of Schuman's career. Swayne does not seem to think highly of Harris or his music, it would seem. Polisi does not say much about Harris in his book, either; in fact Polisi's book has no index entry for Harris.

Orpheus in Manhattan has an excellent index, a list of works, nearly a hundred pages of notes, happily with running headers showing the page range for the numbered note; bless Oxford for this. I mentioned above the "staggering" number of acknowledgements; I attempted to count them but lost track after about four hundred. Swayne's work was assisted in part by very many librarians and archivists, as well as well known musicologists and others, identified by institution. Some of them he labels "saints." This author clearly likes people and clearly he has charmed many into helping make this hugely detailed book a brilliant success. The whole project represents an immense amount of work. He began it in 2003 and, with the help of an NEH fellowship, he was later able to devote two years full time to it.

Strongly recommended.

Copyright © 2011, R. James Tobin