The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

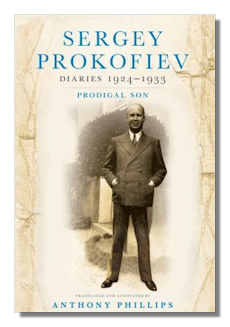

Sergey Prokofiev

Diaries 1924-1933

Prodigal Son

Translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips

London: Faber and Faber, 2012. 1125 pages

Index, illustrations

ISBN-10: 0801452104

ISBN-13: 978-0801452109

This volume completes the publication in English of all the surviving diaries which the composer Prokofiev began at age sixteen and continued through nearly all of his self-imposed exile in the West – mostly in Paris – before he decided to return to his native Russia with his wife and two sons. The total number of pages in the three volumes, including indexes and notes by the translator/annotator (often forward-looking and which cumulatively would fill a volume of hundreds of pages by themselves) come to 2735, about twice the length of War and Peace.

Prokofiev's lengthy accounts of girlfriends and lovers are a thing of the past now. At the outset here he is about to marry Lina Codina, pregnant with his first son, whom he calls Ptashka throughout this diary. The worst of his financial difficulties are past also. By the end of the volume he has completed all five of his piano concertos, his first four symphonies, and all of the ballets he wrote for Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes. He is still having difficulty getting his operas produced and his works printed well in a timely manner. but his concerts generally end in ovations. He is very busy with commissions, and negotiates some at very favorable terms.

He is prosperous enough to purchase two cars, but not enough to buy a house or apartment. He moves constantly, always looking for a summer home with a garden and preferably near the sea. He sees a great deal of Stravinsky, his rival with whom he is generally on good terms. He travels to America. After an enormous reluctance, owing to his concern that he be guaranteed the right to depart freely – which for now he receives – he returns to the Soviet Union several times, When in Russia he travels back and forth between Moscow and Leningrad, as St. Petersburg was called under the Soviets. He maintains contacts with friends and relatives in Russia, particularly the composer Nikolai Myaskowski, his friend since his youth.

Prokofiev has social and business relations with many other individuals, who are almost all identified by the extensive and enormously learned annotations of his English translator and commentator – not his editor – Anthony Phillips. The index to this and the other volumes helps one keep track of these names, and the notes sometimes refer back to previous volumes in which they first appear. Interestingly, by the 1930s Prokofiev finds himself reading his diaries from previous decades to revisit the person he was then. He notes that he is much changed.

What is not available in these diaries, especially this installment, is enough description by Prokofiev of some of these individuals to make them come fully alive to the reader. These are diaries, not fiction or even memoirs, after all. He knows who these people are. He does make the characters of many of them very real, however, particularly Boris Bashkirov who after being rather an impressive person in the first volume has by the middle of this one become rather a disaster, in debt and a mooch.

Prokofiev is still interested in chess – though not as much – and bridge, less of an interest. His new interest is Christian Science, to which he becomes committed to the extent of having his son inoculated against chicken pox only because otherwise the child will not be permitted to begin school in Paris. He claims that meditations based on Christian Science help end his headaches, which he suffers from distressingly often. This also helps him let go of anger directed at people.

Besides anger, a negative characteristic of this composer, in my view is his tendency to despise the work of a remarkable number of composers whom I for one like and admire, whose names I shall refrain from mentioning. But again, he is writing for himself.

It has taken me a long time to read these thousands of pages, which I have done evenings after writing my own pages, but the experience has given me sufficient pleasure to anticipate re-reading them in the future, an activity I have done with very few books in my lifetime. Even though not everything about Prokofiev is admirable, he produced some of the greatest music of the last century – and some remarkable diaries.

Copyright © 2013, R. James Tobin