The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

- Charles Ives Society

- The Influence of George Ives on His Son Charles

by J. Ryan Garber

Recommended Links

Site News

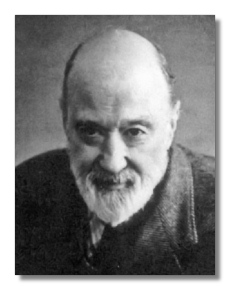

Charles Ives

(1874 - 1954)

Most writers consider Charles Edward Ives (October 20, 1874 - May 19, 1954) the first composer to work in an idiom distinct from that of Europe and to genuinely express an American ethos. Leonard Bernstein called him "our Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson of music." Earlier composers – like William Billings on the one hand and Edward MacDowell on the other – had tried to express the United States in music, but their efforts were either too tied to smaller, vernacular forms or had owed too much in idiom and structural approach to contemporary European models. It's hard to tell MacDowell from Schumann, for example, unless you talk about quality. Ives was the first American who didn't sound like anybody in Europe – not Brahms, not Wagner, not Debussy.

Ives tried to express the entire spirit of the country, from its high ideals to its middle-brow sentimentality to its low-life, ragtime energy. Beethoven, the rebel, rose as an ideal before him. In many ways, Ives represents the last of the Nineteenth-Century New England Transcendentalists, as his Essays Before a Sonata makes clear. If some composers' music sings and others' dances, Ives' talks – philosophy carried out by other means.

Throughout his composing life (which ended in 1927), he was known only to a few specialists and had little immediate influence. In the 1930s and 1940s, his music began to gain wider exposure. Indeed, his Third Symphony (1911) received the 1947 Pulitzer. However, the Sixties saw a breakthrough to a wider audience, and writers in general began to regard his music as iconic.

Several myths have grown up around Ives. Contrary to the picture of him as a sort of Yankee hick puttering around in his shed, he received a thoroughly professional training at Yale from the American Wagnerian Horatio Parker. Indeed, he worked as a professional musician (church organist) for fourteen years. Because the music startles so, many have concentrated on his technical innovations – quartal harmonies, polytonality, polyrhythms and polymetrics, expanded harmonies and dissonances, atonality, and so on – and marveled that he came up with them years before such figures as Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Bartók. Ives himself contributed to his own legend by changing dates on his manuscripts years after the fact. Indeed, scholars have had to come up with ways of assigning dates to his work other than by accepting what he claimed on his manuscripts. Ives and his supporters missed the point. It doesn't matter who gets there first, but who does it well.

During his lifetime, Ives made his public career in insurance. Through a combination of innovative sales techniques and his invention of "scientific" estate planning, he built the largest insturance firm in America, Ives and Myrick. His business innovations are still used. He composed mainly at night and on weekends, and his business success allowed him to hire professional musicians to play through his scores, not always successfully. Although a wealthy man, he and his wife, Harmony (great name for a composer's spouse!), maintained a "proper" facade but lived frugally, a bit like New England farmers in the midst of Gotham. According to several sources, they didn't keep their New York mansion very well heated.

Ives' output divides into three main phases. Despite early experiments carried on with his father, George, he first begins writing according to Germanic models. The Variations on "America" for organ (1892; rev. 1910 & 1949) look to the American Dudley Buck, but show a more rambunctious sense of humor. At Yale, he studies with Parker. Parker rejects the experimentalism, and Ives, a bit ungratefully and to the end of his days, snipes at Parker as a genteel fogey. His graduation exercise with Parker is his Symphony #1 (1898; rev. 1908), a fairly advanced work, although here and there awkwardly carried out. Ives modeled it on Dvořák's "New World" Symphony (1893) but can't resist his satisfying his own intellectual restlessness, as in the first movement, where he seems determined to modulate through all the keys. His big work after Yale, the oratorio The Celestial Country (1902; rev. 1913), looks back to Parker's Hora novissima. Ives wrote it with the idea of scoring a huge success, but it received only lukewarm reviews. However, Ives also indulged his experimental side, as shown by his polytonal 3 Harvest Home Chorales, from the same period. Nevertheless, Ives' main thrust is a new kind of Americana, as in his String Quartet #1 "From the Salvation Army" (1900; rev. 1909) and his Symphony #2 (1902; rev. 1909). Quotation is the main device. In the case of the quartet, movements are based on well-known Protestant hymns. Ives goes further than this in the symphony, practically dispensing with the idea of symphonic themes for a collage of ideas, ranging from Brahms to hymns, college songs, ballads, spirituals, and patriotic anthems. This phase reaches its height in the Third Symphony.

Ives' final phase is his longest. One may characterize it as radically experimental. It includes The Unanswered Question (1908; rev. 1935), Central Park in the Dark (1909; rev. 1936), Study #9 "The Anti-Abolitionist Riots" (1913), General William Booth Enters into Heaven (1914; rev. 1933), String Quartet #2 (1915), the Orchestral Set #1 "3 Places in New England" (1917; rev. 1921), the Symphony #4 (1918; rev. 1925), the Piano Sonata #2 "Concord" (1919; rev. 1920s-40s), 114 Songs (coll. 1922; the only work Ives published himself), Psalm 90 (1924), and the Universe Symphony (1915-28; incomplete).

In 1918, Ives suffered a heart attack, which led to his retirement from Ives & Myrick. He now had time to compose. In 1927, however, he gave up new composition. "Nothing sounds right to me any more," he said. Nevertheless, he continued to revise earlier work or to make new arrangements, often spurred by the rare upcoming performance. Ives however resisted calling any of his compositions finished. He often had second and third thoughts, playing various versions of passages to performers and telling them to choose what they preferred. This has led to massive editing and re-editing efforts on the part of scholars and composers trying to establish a "true text." This effort continues, more than fifty years after the composer's death.

The Twenties saw the beginnings of his influence on younger, radical composers – Henry Cowell, Ruth Crawford Seegar, and Carl Ruggles among them. In the Forties, this spread to composers like Elliott Carter, William Schuman, and Morton Gould. The Thirties brought performances by Slonimsky, Kirkpatrick, and Bauman, and publications by various new-music presses. Bernstein made a landmark recording of the Second Symphony in the Fifties (a performance which Ives heard at his Connecticut farm over the radio). However, the Sixties saw a real boom in Ives' stock with a flood of recordings and performances. Peter Schickele's P.D.Q. Bach to some extent parodied not Ives himself, but some of Ives' more foolish idolators.

Ives is known mainly for his orchestral scores, but his vocal contributions stand out as well. He is one of the great choral composers, and his songs populate a wide area of means and expression, from German-style Lieder, cowboy songs, and campaign songs to highly experimental pieces. Even his experiments depict a huge range of experience – from Transcendentalist nature poetry to parlor ballads and Victorian hymns.

In his determination to take in and express the entire American experience, he became our musical equivalent to Walt Whitman. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Piano Sonata #2 "Concord"

- Piano Sonata #2 "Concord, Mass., 1840-1860"/Nonesuch 971337-2

-

Gilbert Kalish (piano)

- Piano Sonata #2 "Concord, Mass., 1840-1860", Op. 26 with Barber/Hyperion CDA67469

-

Marc-André Hamelin (piano)

- Piano Sonata #2 "Concord, Mass., 1840-1860" with Piano Music/Vox Music Group CDX5089

-

Nina Deutsch (piano)

Three Places In New England

Three Places In New England

- First Orchestral Set "Three Places in New England" with Mennin & Schuman/Mercury 432755-2

-

Howard Hanson/Eastman-Rochester Orchestra

- First Orchestral Set "Three Places in New England", Orchestral Sets #2 & 3/Naxos 8.559353

-

James Sinclair/Malmö Symphony Orchestra & Chamber Chorus

- First Orchestral Set "Three Places in New England", Symphony #4, Central Park in the Dark /Deutsche Grammophon 423243-2

-

Michael Tilson Thomas/Boston Symphony Orchestra

Symphonies (#2)

- Symphonies #1 & 4 in D minor/Sony SK44939

-

Michael Tilson Thomas/Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #1 & 2/Chandos CHAN10031

-

Neeme Järvi/Detroit Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #2 & 3 "The Camp Meeting"/Sony SK46440

-

Michael Tilson Thomas/Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam

- Symphony #2, Central Park in the Dark, The Unanswered Question, etc./Deutsche Grammophon 420229-2

-

Leonard Bernstein/New York Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #3 "The Camp Meeting"/Mercury 432755-2

-

Howard Hanson/Eastman-Rochester Orchestra