The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

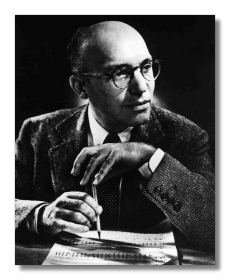

Kurt Weill

(1900 - 1950)

The son of a Dessau cantor who also composed Jewish liturgical music, Kurt Weill (March 2, 1900 - April 3, 1950) became, with Benjamin Britten and Alban Berg, one of the three most influential opera composers of the Twentieth Century. In many ways, he was far more formally innovative and versatile than either. Almost every one of his stage works approaches the problem of musical drama in a different manner.

Weill, who would have studied with Arnold Schoenberg had the money been available, instead became part of Ferruccio Busoni's master class. However, he had written with astonishing assurance in his late teens, even before he had met Busoni, and many of his masterpieces had appeared before he reached the age of thirty. Weill died relatively young, a smidgeon over fifty, so in a sense all of his works are early. Remarkably, almost every one of them displays strong, readily-identifiable individuality and maturity of thought and craft.

Weill's early music shows the influence of Max Reger, Gustav Mahler (which he never entirely escaped), Schoenberg, and (no big surprise) Busoni, particularly the Busoni of Turandot and Arlecchino. Highlights of this period include Symphony No. 1 (1921), the ballet Zaubernacht (1922; staged in New York, incidentally), the chamber song cycle Frauentanz (1923), Recordare (1923; an extended choral masterpiece), the Violin Concerto (1924), and the one-act opera Der Protagonist (1926). In all these works we find a strikingly distinctive voice, but still not in the idiom we associate with Weill. The "free tonality" of Schoenberg is still apparent, as is a Mahler-like propensity for grotesque and haunted landscapes. Weill once remarked that no one could hope to understand his concerto if they didn't know Schoenberg. It's an exaggeration, of course, but with a kernel of truth.

Weill's first stylistic breakthrough comes with the appropriately-named cantata Der neue Orpheus (1925), where he discovers how to use the sounds of cabaret music in a classical context. This belongs to the European discovery of jazz in the Twenties, along with Milhaud, Stravinsky, Poulenc, Honegger, Satie, Hindemith, and Schulhoff. But Weill creates something all his, a music in turn simple and slightly sour. Thus begins the mature "European Weill," from about 1927-1933: Mahagonny Songspiel (1927), Die Dreigroschenoper (1928), Happy End, Der Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (1927-29), Der Lindberghflug (1929), Der Jasager (1930), Die Bürgschaft (1931), Der Silbersee (1933), Die sieben Todsünden (1933), and Symphony No. 2 (1934).

With royalties from Dreigroschenoper and from several fugitive Schläger, Weill became free to work on whatever he wished. He also drew the envy of Schoenberg and his mouthpiece Adorno, who advanced the proposition that any music so popular couldn't be any good. Serious art that engaged the times was by its nature misunderstood by all except the most high-minded souls. It was bull and it was petty. Weill, however, refused to descend into the pit and continued to praise Schoenberg, although he didn't follow the older man into serialism. Indeed, Weill's aesthetic, exemplified by his work, pleads for stylistic pluralism: one can make good music more than one way. Added to this, dangerous political currents began to bubble up. Weill had flourished in the years of the Weimar Republic. By 1932, the Nazis, although not yet in power, still exercised an unwholesome influence on the arts. As a Jew, a Modernist, a political left-winger, and the most successful German theater composer of his day aside from Richard Strauss, Weill became a large target. Theaters that had clamored for Weill's work no longer asked him. Current productions were removed from the boards. His chief publisher had begun to withhold royalties and to reject new scores. In 1933, when the Nazis imposed draconian censorship laws after the Reichstag fire, Weill fled to Paris but found the city uncongenial to his work. He next tried London, with even less success. So in 1935, he sailed for New York for a production of his super-pageant Der Weg der Verheissung, now slightly rewritten and renamed The Eternal Road. When the production ended, he chose to remain in the United States, and thus began to create the "American Weill." He began writing much as he had for Europe and gained critical, though not popular, success with The Eternal Road and Johnny Johnson (1936). Weill had to learn how to write "American" pop. He never did quite get the hang of it. He never turned into Harold Arlen, Hoagy Carmichael, Richard Rodgers, or even Vernon Duke (another emigré), but he finally found success with the Broadway show Knickerbocker Holiday (1936), which yielded perhaps his most enduring hit, "September Song." Incidentally, "September Song" was a rewrite of a number for a flop show written in Europe. He followed this up with Lady in the Dark (1940), One Touch of Venus) (1943), and after the War, Street Scene (1946). From these shows came "My Ship," "The Saga of Jenny," "Tchaikovsky," "One Life to Live," and "Speak Low." All of these shows revolutionized Broadway musical theater, and none of them resemble one another. Their influence was felt in the "art musical" movement, which included such composers as Rodgers, Moross, and – most spectacularly – Bernstein, and Sondheim. I doubt you would have had Pacific Overtures without the stylizations of Lady in the Dark or the musical-as-verismo West Side Story without the example of Street Scene. His final years produced the "college opera" Down in the Valley (1948), claimed by some as his most-performed American work, and Lost in the Stars. He was working on a musical of Huckleberry Finn when he died of heart disease.

By 1950, however, the Young Turks (some of whom were a bit long in the tooth by then) had proclaimed Weill's music obsolete and that he had prostituted his art in America. Again, most of these criticisms stem from Adorno. However, the off-Broadway revival of Die Dreigroschenoper as Marc Blitzstein's Threepenny Opera ran for years and years and got many people to take a look again at Weill's complete work. Weill studies began in earnest around this time, although it took at least twenty years for critical consensus to begin to go Weill's way. Even so, it at first sharply divided between pro-Europe and pro-American champions. However, by the late Seventies scholars and critics like David Drew had shaped a more integrated view. We now see Weill as the most protean dramatic composer of his time and a composer of very wide influence – from Copland, Britten, Henze, Ligeti, and Adams to Bernstein and Sondheim. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Three Penny Opera

- Three Penny Opera (1928)/CBS MK42637

-

Lotte Lenya (voice), Wolfgang Neuss (voice), Willi Trenk-Trebitsch (voice), Trude Hesterburg (voice), Erich Schellow (voice), Johanna von Kóczián (voice), Wolfgang Grunert (voice), Inge Wolffberg (voice), Kurt Hellwig (voice), Paul-Otto Kuster (Tenor), Josef Hausmann (voice), Martin Hoepper (voice), Wilhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg/Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra & Günther Arndt Choir

- Three Penny Opera (1928)/RCA Victor Red Seal 166133

-

Heinz Karl "Nali" Gruber (baritone), Nina Hagen (voice), Max Raabe (voice), Sona Macdonale (voice), Hannes Hellmann (voice), Winnie Böwe (voice), Timna Brauer (voice), Jürgen Holtz (spoken vocals), Heinz Karl "Nali" Gruber/Ensemble Modern

- Three Penny Opera (1928)/Sony 51520

-

Glenn Kezer (voice), Ellen Greene (voice), Raul Julia (voice), Elizabeth Wilson (voice), Robert Schlee (voice), Roy Brocksmith (voice), Tony Azito (voice), Jack Eric Williams (voice), C. K. Alexander (voice), Caroline Kava (voice), David Sabin (voice), Blair Brown (voice), Joseph Papp/New York Shakespeare Festival 1976