The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rosner Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

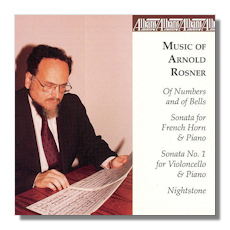

Arnold Rosner

Chamber Works

- Of Numbers and of Bells, Op. 79

- Sonata for French horn and piano, Op. 71

- Sonata #1 for Violoncello and piano, Op. 41

- Nightstone, Three Settings from The Song of Songs, Op. 73

Timothy Hester & Nancy Weems, pianos

Heidi Garson, horn; Yolanda Liepa, piano

Maxine Neuman, cello; Joan Stein, piano

Randolph Lacy, tenor

Albany Records TROY163

I first came across Arnold Rosner's music by accident. I had bought a CD in Harmonia Mundi's "Modern Masters" series (HMU 906012) for something by another composer and, like Saul on the Damascus got struck with the force of revelation by Rosner's Responses, Hosanna, and Fugue for strings. This was mostly everything I ever wanted music to do. Unfortunately, Rosner got there ahead of me.

This disc confirms and extends my first impression – four very handsome, noble works. The notes by producer John Proffitt provide a fine introduction to the music. In fact, they steal a lot of my thunder. Nevertheless, I'll give my impressions of the music anyway, on the chance that this may persuade you to seek out the CD and more.

Rosner's characteristic mode is "epic," and thus he shares characteristics with Hindemith, Bloch, Vaughan Williams, a bit of Bernstein (particularly the symphonist), and even Hovhaness. In fact, his music moves in a more classically modernist than post-modernist way, with a large regular rhythmic tactus, tonal counterpoint, and Romantic symphonic phrasing, as opposed to fluid, free rhythm, planes of sound, and isolated gestures. Furthermore, he has fashioned a personal, instantly-recognizable idiom – another link to the classic Modernists. Individuality may not be everything, but it's not nothing, either. If you want Rosner's music, you really have to go to Rosner.

Talking about Rosner's technique – and he does know his compositional onions – seems really beside the point. The considerable technique doesn't serve its own ends, but big, expressive ones. The pieces have a healthy ambition to them. They deal in big "ideas." They take long breaths and giant strides, rhetorically speaking. If you know the Bloch Avodath Hakodesh, you have some idea of the scale on which Rosner works. This musician wants to exalt the listener. That is, in fact, the glory and the limitation of the pieces recorded here. I sure hope Rosner writes to satisfy trivialities as well. We don't live on an exalted plane all the time, and, furthermore, most of us don't want to. A really great artist (if I didn't think Rosner capable of that, I wouldn't mention it) speaks to our lives as a whole. After all, even Bartók wrote a Divertimento.

Of Bells and of Numbers forsakes the usual 2-piano strategies of stereo and of the orchestra-in-little. In its place, Rosner constructs competing rhythms over a ground idea (unconventionally in the highest part, rather than the lowest) of rapid tintinnabulation (the "bells" part of the title). As Rosner points out:

"To codify just one example: at 5:40 into track 1 of this recording, the first piano right hand plays a line in flute range in straight 4/4 meter consisting of mixed 8th and 16th notes. The left hand is in baritone range in unvarying 8th notes, but the melodic and accent pattern amount to 11/8. The second piano uses both hands to play a modal chorale in mid-range in notes precisely 5/16 long."

Despite the complication (and, to give Rosner credit, it sounds more powerful than complicated), we find the piece's emotional point in the chorale – a swirl of activity, from which rises a hymn of great beauty. Of Bells and of Numbers rarely, if at all, modulates (depends on what you count) over its fifteen minutes and the bell idea sounds fairly constantly throughout. The work may consequently remind some of minimalism, but the score's ethos could hardly stand further away. Rosner considers dramatic conflict a musical virtue. It's not just "process" eventually working itself out, but real drama unfolding. Hester and Weems triumph over the rhythmic complications to give a stunning, committed performance.

The two sonatas share many structural similarities: declamatory, prophetic first movement, scherzo second, and meditational finale. Rosner himself points out the range similarities of the two instruments perhaps influencing the music written for both, and Rosner's harmonic idiom, based largely on fourths and fifths and on key-center changes thirds apart, also imparts to the music a family look. Still, each sonata tries to work with its respective instrument's "soul." In a better world, both would be standard repertoire.

The French horn sonata starts out with a passacaglia (usually, melodic variations over a ground bass). It certainly feels like a passacaglia, but I have trouble grasping the entire theme. It really doesn't matter, because again Rosner plays a much harder game than merely filling a form: he battles for a listener's soul. The fourths and fifths in Rosner's language become solemn fanfares in the horn. It conjures up in my mind the ram's horn blown from high ramparts over the desert. The second movement is heady high spirits, with double- and triple-tonguing from the horn player and a nobly singing trio. In the slow finale, the horn sings soaring and beautiful thoughts. It's the kind of piece that's probably beyond another composer's envy. One doesn't say, Damn, I wish I'd written this, but I couldn't have written this, because I couldn't have thought of it. It's not a matter of acquiring the right technique, but of changing the person you are. Heidi Garson has mastered the difficulties of her part, but the pianist, Yolanda Liepa, overshadows her with some ravishing playing.

The cello sonata's first movement broods, with some near-eastern melismata for relief. The second movement consists of a remarkable and rugged fugal scherzo which explodes and stamps off angrily at the end. The finale begins with a theme reminiscent of Gregorian chant and flowers into 7/8 hymns. The performers do well enough to give you a decent idea of the sonata's stature, but otherwise provide little excitement of their own. They come off best in the scherzo but give little shape to the substantial slow movements.

If we divide composers into singers and dancers, Rosner definitely is a singer, despite his rhythmic interests. Nightstone just about raptured me out. Unfortunately, Randolph Lacy, the tenor, fails these songs on several grounds. His intonation is shakey, for one, with a tendency to sink flat. Also, for some reason, his tone occasionally sounds "dead" – his vibrato quits altogether – usually at the beginning of a phrase's plateau. It's an unpleasant habit, and turns his tone into a "bleat." Finally, he seems uneasy with the work's normative 5/8 meter, as if it catches him off-guard – lack of practice? Direction and color in the performance comes almost entirely from the pianist, Timothy Hester. I would have loved to have heard a younger Ian Partridge tackle these.

Once again, thanks to producer John Proffitt and Albany Recordings for a superior effort. Their love for their catalogue is obvious.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz