The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

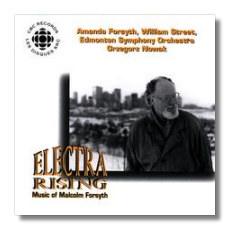

Malcolm Forsyth

Electra Rising

- Cello Concerto "Electra Rising"

- Valley of a Thousand Hills

- Saxophone Concerto "Tre Vie"

Amanda Forsyth, cello

William H. Street, alto sax

Edmonton Symphony Orchestra/Grzegorz Nowak

CBC Records SMCD5180 73:59

Summary for the Busy Executive: Vigorous, handsome music.

Born in South Africa, Forsyth emigrated to Canada, where he has apparently made a living, to judge from his commissions. I first heard his music on a Pro Coro Canada disc (Arktos Recordings 96014CD), and his strong grip on form impressed me greatly. Forsyth not only could handle complication - in this case, the sudden switches of thought in texts by John Donne - but could create something expressive. This CD both reinforces that impression and adds to it.

Unlike, say, Copland, Forsyth hasn't an immediately-recognizable voice, but that doesn't really matter. He has instead an individual personality or attitude toward his materials. The idiom is kind of post-Walton, à la Alwyn. If you can handle either of those composers, Forsyth's music should give you little trouble. The basic impulse of the music is classic Modern, rather than avant-garde contemporary. Forsyth's distinction lies in his approach to form. Almost all the works here are a bit odd and frequently quite daring structurally. Yet, the composer brings them off with such aplomb, a listener could miss the quirks. The music, above all, strikes me as the work of a consummate pro, with a marvelous orchestral and contrapuntal imagination.

The most eloquent work on the program (and, happily, the most recent - 1995) is the cello concerto, "Electra Rising," written for the composer's daughter, Amanda. A mere recital of the movement titles - "Cadenza. With gossamer lightness," "Mayibuye Afrika! Scherzo-like; strictly rhythmic," "Cadenza. Dramatic," and "Paean. Hymn-like; radiant" - reveals Forsyth's idiosyncratic mind. With the first movement in particular, one faces with the composer the challenge of a ten-minute "cadenza" - actually, an accompanied cadenza, much like a similar passage in Elgar's violin concerto - a freely rhythmic song in the solo instrument against mainly a background of chords. This could easily degenerate into aural soup or the equivalent of nattering, but there really is a symphonic argument here which the listener can follow without strain. It's also intensely beautiful. The second movement is polyrhythmic counterpoint in mixed meters. It may also be that individual instruments could be in different meters - for example, 3/4 + 7/8 in one line and 2/4+5/8+2/4 in another simultaneous line. The opening orchestration evokes for me the sound of the African thumb piano, although one of symphonic size. Exuberant, the movement celebrates the end of apartheid in Forsyth's birthplace of South Africa. I catch snatches of African tribal dancing as well.

The second "cadenza" movement somewhat reverses the first. This time the orchestra material mostly takes up the thematic argument, while the cellist explores all the way the instrument can make chords - strumming, plucking, bowing, arpeggiating, and so on. Although half the length of the first movement, this cadenza runs the same artistic risk. Yet it comes across as lyrical, rather than contrived, even though it lacks a "hummable" tune. The finale is essentially another slow movement (the concerto has three altogether), but this time the soloist gets to sing in the way we associate with the instrument. The composer's indication "radiant" hits the mark of the music's character.

The composer's daughter and inspiration takes up the solo part, and, far from being Daddy's Little Indulgence, she's probably one of the most distinguished string players I've heard. A cellist friend of mine once divided cellists into two camps: roughly Casals vs. Feuermann or Rostropovich vs. Starker - a big tone as opposed to a clear one. I tend to favor the Feuermann, Fournier, and Starker camp, and Amanda Forsyth belongs there. A student of, among others, William Pleeth, she has mastered color, dynamics, and phrasing and has a grasp of musical architecture few players achieve in a lifetime. She's still in her thirties. I wish her a great career.

Valley of a Thousand Hills, a three-movement evocation of South African landscape and culture, lightens up emotionally. I've not seen South Africa, so I'm not sure what pictures, if any, the music should bring forth. The most conventionally descriptive movement is the second, "Mkambathini," the Zulu name for Table Mountain. The music puts it off in the distance or surrounded by mist. More than that, however, the three movements are all technically "about" ostinato and orchestration. Despite that description, this isn't minimalist music. It lacks the expanded time-sense of most minimalist work. Development happens within "normal" time frames. Nevertheless, Forsyth risks stasis with his ostinati, although he always knows when to move on. Furthermore, he uses the patterns to create something new and expressive. For example, the striking opening of the first movement, "Horizons," builds the music before your very ears, as the main theme looms out of wispy fragments and becomes a buoyant dance. Forsyth also constructs a nifty transition between the second and third movements, the latter called "Village Dance." Here we get Crestonian cross-rhythms in unusual meters (according to the liner notes, 17/8). Forsyth scores so clearly that we actually hear each contributing strand to the polyrhythm. Nowak and the Edmonton Symphony do a very good job with these.

The saxophone concerto is also a bit of an odd duck. Conceived in three movements, each inspired by one of the Roman highways (Appian, Flaminian, and Salarian), it wound up with four. During its composition, Messiaen died, and Forsyth wrote a second-movement homage. Forsyth's music isn't particularly Messiaenic, but perhaps Forsyth simply wanted to acknowledge the passing of an influential figure, one who touched the musical thinking of so many after the Second World War.

The opening ("Presto, ritmico. Like a meteor") makes use of the by-now familiar ostinati and cross-accents, mainly in five, this time to create something like a Middle Eastern dance. Stravinskian pesante chords make their appearance as well. The liner notes find a link to the "Mediterranean" Walton, which I don't hear myself. At any rate, the bouncy rhythm gives way to an intense singing from the sax, before the bouncy part returns. The scoring is preternaturally transparent. The second-movement "Ommagio à Messiaen (1908-1992)" is essentially an extended cadenza for the instrument. The only musical links I can discover to the French composer are a kind of "suspension of time" and a discreet use of percussion and slightly out-of-the-way string effects. This leads directly to the slow third movement, "Melancolico" (shouldn't that be "malinconico?") - where the sax sounds as if in a slight funk. The finale follows without pause. The spirited rhythm dispels the longeurs of the "Melancolico," but the harmony retains its astringency. It's an energetic, but not particularly happy ending.

William H. Street, a performer new to me, plays with a tone so clean, so free of fuzz, that at times his instrument sounds like a clarinet. It's a good job. The recorded sound is fine.

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz