The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Liszt Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Franz Liszt

Complete Symphonic Poems

Volume 1

- Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne, S. 95

- Tasso: Lamento e Trionfo, S. 96

- Les Preludes, S. 97

- Orpheus, S. 98

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10341

Volume 2

- Eine Fast-Symphonie in drei Charakterbildern (nach Goethe), S. 108

- Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe, S. 107

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10375

Volume 3

- Mazeppa, S. 100

- Héroïde funèbre, S. 102

- Prometheus, S. 99

- Ferstklänge, S. 101

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10417

Volume 4

- Hungaria, S. 103

- Hamlet, S. 104

- Hunnenschlacht, S. 105

- Die Ideale, S. 106

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10490

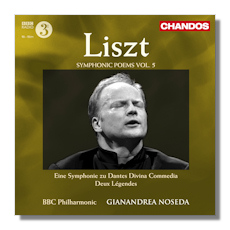

Volume 5

- Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia, S. 109*

- Deux Legendes, S. 354

* Gillian Keith, soprano

* Ladies Voices of the City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10524

In the early 1850s (probably in 1853), when Liszt was living in Weimar, he invented the term (and, indeed, the genre) Symphonische Dichtung for compositions (of his) which had inspirations from outside music… the worlds of poetry and other literature, painting, legend and characters from history. Between 1848 and 1858 Liszt wrote a dozen such "symphonic poems". The first six were published in 1856; the rest between 1857 and 1861.

Composers had used extra-musical themes, events and personages as inspiration, of course before this. Indeed, many of Liszt's earlier piano works from the 1830s were inspired by writing, by places, by atmospheres even. But in the "symphonic poem" Liszt "designed" and developed such extended, thematically – and instrumentally – unified works – always for orchestra – into a specific, strong and identifiable genre. This freed the orchestra from more restricted circumstances in which it could play. It could now work outside the (four movement) symphony, concerto or operatic repertoire. The Symphonic Poem can be seen as paving the way for greater fluidity of broader musical development in the century that followed.

Gianandrea Noseda is the effervescent outgoing conductor of the BBC Philharmonic (leader Yuri Torchinsky). Born in Milan in 1964, Noseda was the first foreign Principal Guest Conductor at the Mariinsky Theatre (St. Petersburg) in 1997; there he also set up "Mariinsky Young Philharmonic Orchestra" with Valery Gergiev and served as its Principal Conductor. Other high profile posts have included Principal Guest Conductor of the Rotterdam Philharmonic (1999-2003) and of the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI (2003-2006). Now recording exclusively for Chandos, Noseda and the BBC Philharmonic have made a splash in several areas – including the current superb cycle of Liszt Symphonic Poems on five CDs. This cycle has the additional merits of including both some of the lesser-heard pieces, like Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne, S. 95, Héroïde funèbre, S. 102 and Die Ideale, S. 106 and the other major orchestral works, the Dante and Faust symphonies, for instance.

It used to be thought that, because these were – amazingly – among the first orchestral works that Liszt wrote, the composer's assistants were employed to complete sketches. This is almost certainly not the case: Liszt's skills extended to much more than merely adequate orchestration on top of forging a new musical genre. It must be said at the outset that Noseda and the BBC Philharmonic take the music at face value, make no allowances, and play it all as music, not as a series of a dozen or so historical curiosities. On balance, the advantages of a single conductor with a single orchestra with all the consistencies and deepening insight (the works appear on these five CDs very roughly, though not exactly, in the order in which they were written) are many. Had Chandos chosen multiple personnel for this series, this sense of acceptance might not have been so strong, for example. Not for nothing can the BBC Philharmonic (formerly the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra) now be regarded as a leading world orchestra with very solid repertoire and many accolades for the breadth and depth of its interpretations.

The first CD (CHAN10341) starts with actually the first Symphonic Poem, and the longest if you exclude Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe, S. 107, which was composed at the end of Liszt's life, Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne, S. 95. Inspired by a poem of Victor Hugo counterposing nature and humanity, it's actually in five animated movements. Perhaps not the most inspiring or arresting way to begin the series, the playing is nevertheless solid and secure. Tasso, of course was written for the play by Goethe, performed in recognition of the centenary (in 1849) of author's birth. But Liszt felt the need also to include references to Byron's poem, "The Lament of Tasso" – hence the full title. This, too, receives a spirited and perceptive interpretation and shows the fire blended with empathy for his subjects of which Liszt was capable. In places, it may be considered just a little too "brassy", but not brash. Les Preludes, S. 97 is probably Liszt's most popular and best-known work in the genre. Here, Noseda definitely elicits greater sensitivity and delicacy from the BBC Philharmonic. A somewhat monolithic theme which appears in variation runs a number of risks. A good, forward recording in the responsive acoustic of Studio 7 of New Broadcasting House in Manchester, together with imaginative tempi do ensure that the true import of the piece (that life itself is a series of preludes to death) is not lost. The musicians have a firm grasp of structure… nothing wanders. Orpheus, S. 98 is often one of the most highly thought-of of the Symphonic Poems. Also using the characteristic ABA format (but in a single, longer, movement) it alludes to (rather than portrays) Orpheus, originator of song. This means lyrical and flexible scoring, which is ably pulled out by Noseda. The playing is sweet, tender almost, certainly very sensitive – especially on the part of the strings, towards the middle of the piece, for example. But never overdone, or sickly. Certainly the most persuasive and beautiful performance on the first CD.

CHAN10375 contains the Faust Symphony and From the Cradle to the Grave. One of Liszt's most evocative works, with much in it that's at the very center, too, of many of Liszt's major concerns as a musician and as a human being. Excitement tempered with finer feelings; variety; an at times almost raw (that is, no matter how gentle or fierce, never contrived) energy; great skill and originality in scoring. And of course wonderful melodies. These are all characteristics of this exemplary performance by Noseda and the BBC Philharmonic. The Faust Symphony is another example of the ways in which Noseda treats the music as illustrative of an eternal theme, rather than a curio or derivative adjunct to Goethe's work, or to Liszt's own solo piano œvre. Every bar of the three parts (in ten, three and four movements) is both valid music in its own right and sensibly serves the wider purpose of the work as a whole – for all its relevance to the Faust legend as created by a near contemporary of Liszt's. The much shorter Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe, S. 107 ("From the Cradle to the Grave") is played with every bit as much sensitivity and great attention to dynamics. This is truly a work that describes life. Program music in the sense which later in the century became much more common. It was composed much later, of course: between 1881 and 1882, towards the end of Liszt's life. Inspired by a picture sent to the composer by Mihály Zichy suggesting the passage through life. Again in three sections, each clearly depicting the corresponding stage in life, Noseda very successfully and convincingly directs the passage from quietude and peace through struggle to a kind of resignation using expert control and guidance of tempi and dynamics in particular. Nor is he afraid to let silence speak – as it often does so eloquently – two minutes or so before the end, for example. Another truly lovely performance.

The third CD in the series (CHAN10417) includes Mazeppa, S. 100, Héroïde funèbre, S. 102, Prometheus, S. 99 and Ferstklänge, S. 101. The opening of Mazeppa is typical of the snappy, deft and flexible yet fully thought-through approach of Noseda. Mazeppa is another one of Liszt's tone poems with a large simple central theme and supporting… cymbals. Yet conductor and orchestra concentrate instead on the excitement, the instrumentation and the clarity of multiple staccato string chords and punchy brass support. And on the contrasts to that opening idea which successive variations present. You can hardly take a breath from start to finish. At times Mazeppa sounds like an opera overture. In other words, Noseda gets the very best and most from the piece: his account here is sheer excitement and enjoyment without brashness – a mixture of holding back and sensitivity to orchestral sounds with all the thrill of the page, Mazeppa's ride… fitting as much to the Polish hero's real exploits as to Liszt's skills. Probably just what the composer would have endorsed. The Héroïde funèbre, S. 102 can be ponderous and heavy. Instead, the BBC Philharmonic takes a light and engaged approach; each twist in the melody is fresh; each alternation of instrumental color is interesting. It's actually the reworked (in 1849/1850) first movement of a "Revolutionary Symphony" from 1830. Noseda's tempi and dynamics confer a gravity on the work that make us wish that Liszt had extended it further. The debt to Berlioz is not overplayed. The somberness is taken completely as Liszt must have intended (there's as much funereal as heroic in these impressive 22 minutes, the longest work on the CD): a tribute to those who struggled for a better world; and lost everything. Prometheus lies at the very heart of the concept of the symphonic poem by its use (especially in the opening) of harmony, rhythm and fugue to suggest the struggle of the Prometheus in stealing fire from the gods. Again, Noseda achieves a pleasing balance between the dramatic and the purely musical. Never histrionic; yet full of power. And an interpretation that not only never lingers; but also works nicely exploiting the tensions and releases of Prometheus' precisely conceived five-movement structure. Ferstklänge has a strange history – almost as twisted as Liszt's and Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein's marriage. It probably does celebrate at least the spirit behind that frustrated event. Noseda, yet again, brings out the poignancy of a celebration which is less than perfect. He also accords just more than a touch of joyousness – especially in the opening allegro mosso con brio. While this is not one of Liszt's most successful works, it has its moments; above all its honesty and transparency, to which these musicians respond especially well.

CHAN10490 also has four works: Hungaria, S. 103, Hamlet, S. 104, Hunnenschlacht, S. 105 and Die Ideale, S. 106. As its title suggests, Hungaria is intensely nationalistic with dotted and martial rhythms, brass, percussion and passages for solo violin. Noseda is aware of the dangers of pastiche and successfully leads his players into taking the work at face value, for Liszt was honored both by the commission and reception of the work. Hamlet is more thoughtful. Not any kind of commentary on the play, rather it successfully depicts its moods, atmospheres and character. With markings such as düster (lugubrious) and ironisch, this is the essence of the symphonic poem. Once again, Noseda makes a fine balance between responding (both) to Shakespeare's drama and to Liszt's – through the latter to the former, almost. The variety, the rhythmic and harmonic subtleties are full of interest. Nothing is overstated; yet nothing is missing: Noseda's sensitivity in the slow passages and control of the faster ones add to the feeling that this work should be played more often than it is. Hunnenschlacht is from a painting (by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874), whom Liszt thought very highly of) depicting the legend that the spirits of those killed in the battle of the Catalaunian Fields in the year 451 rose and continued the fight in the air for three days. The Huns, of course, are led by Attila. Without either maudlin or irony, Noseda's reading celebrates the majestical and the hints at serenity (in the quiet organ passages of the third movement, for instance) which for Liszt represented the spiritual significance of this conflict. The playing, of the BBC Philharmonic's strings for example, is nevertheless tight and disciplined. Die Ideale also exemplifies why Liszt developed the genre of the symphonic poem: to communicate the inner, or spiritual, essence of the subject. In this case the occasion was ostensibly the commemoration of Goethe's patron, Carl August. But with words by Schiller firmly in Liszt's mind, Die Ideale must be as much a celebration of the nature of literary (and musical) inspiration as anything more specific. This, of course, is more abstract and disparate than some of Liszt's other centers of interest. One way in which Liszt nevertheless achieves his goal is by some both harmonic and rhythmical experimentation… the keyless introduction to the work, for example. Noseda refuses to make too much of this and concentrates, rightly, on the same essence as it seems Liszt was concerned with. Pleasingly to the point and successful. In fact, their approach to Die Ideale is typical also in the distinct and yet almost transparent way in which – for all their awareness of and attention to each work's larger structure, its architecture – the color and impact of each individual passage has been carefully conceived and is executed with real attention to details without losing sight of the import of each work as a whole. Symphonic indeed.

The bulk (three quarters) of the final CD (CHAN10524) is taken up with the Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia, S. 109, in which Gillian Keith (soprano) and the Women's Voices of the City of Birmingham Symphony Chorus also perform; it ends with Deux Legendes, S. 354. In that the Dante Symphony remains, for some, a bit of a mixed bag and the Legends have less to recommend them than do most of Liszt's other symphonic music, this fifth CD could be seen as a bit of an anti-climax. In fact, it's not. This exciting, precise and spirited account of the Dante Symphony is actually one of the cycle's high points. From first note to last there's the tension and authority of Dante's epic. Again, just what is needed for a Symphonic Poem… reference to, insight into and understanding of the (in this case) work of literature which inspired it. The playing is tight, exciting and full or forward movement. The two legends, of course, are those of "St. Francis of Assisi: the Sermon to the Birds" and "St. Francis of Paola Walking on the Waves". These have yet another attribute, that of the concerto for orchestra; many of the instruments (particularly those in the upper registers, violins, flutes and other woodwind in the case of the first Legend, for example) receive concentrated attention in Liszt's scoring. These are orchestrations of the piano versions anyway. Just as compelling as the fuller symphonic works, they are no miniatures. Rather, in Noseda's hands brightly colored, crystalline patterns of light seen crisply through a polished magnifying glass. Their clarity and freshness make a fitting end to a delightful cycle.

There are rival recordings of several of the Liszt Symphonic Poems available; but only the series on Decca (4782309) by Bernard Haitink with the London Philharmonic Orchestra has them all. So even were Noseda's recordings not so compelling, original and insightful as they are, this would be an important and altogether desirable collection. As it is, it can safely be recommended as the one to get. The recordings are well up to Chandos' high standards, the accompanying booklets well produced and informative. In this bicentenary year, as Liszt gets more attention than usual, it is also such established recordings as these that are rightly gathering the acclaim. Recommended.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.