The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bartók Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

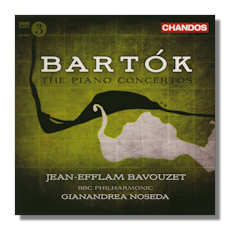

Béla Bartók

Piano Concertos

- Piano Concerto #1

- Piano Concerto #2

- Piano Concerto #3

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, piano

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/Gianandrea Noseda

Chandos CHAN10610

These are sparkling, measured, accurate, characterful, precise and energetic accounts of the three Bartók piano concerti by French pianist, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet. Hats off to Chandos, the BBC Philharmonic and its irrepressible conductor, Gianandrea Noseda, for a release whose freshness, presence and faithfulness to the composer's scores makes it a strong contender for preferred recording of this repertoire.

It's a crowded field… there are between two and three dozen recordings of each concerto in the current catalog, the third being the most often recorded. From the late 1950s Géza Anda and Ferenc Fricsay on DG Classics (now available on Audite 23410) stands out. So does Boulez's more recent performances on DG (4775330) with three different soloists (Zimerman, Andsnes and Grimaud) and orchestras (Chicago Symphony, Berlin Philharmonic and the LSO).

A defining quality of the playing of Bavouzet is not that he is "relaxed", nor quite "carefree". Yet "loose" in the best sense of the word; spontaneous, generous in phrasing, rhythmically and expressively uncluttered. He (and the BBC Philharmonic, by whom the pianist is extremely well supported) is obviously enjoying every minute. There is almost an abandon in the faster movements, an excitement – in the Second Concerto's allegro molto [tr.6], for example – that points up the momentum with which Bartók infused almost all of his symphonic music. (Half of the composer's orchestral music is in concerto form, of course.)

Not that it's an unholy rush: as the tempo changes – subtly, a minute and a half, then two and a half minutes into, then again during the middle bars of, the movement – both soloist and orchestra draw the greatest tension from these contrasts by strictly observing the time signatures, the cross rhythms; and then the beauty of the staged rallentando in the last minute. Almost a little symphonic study in itself as opposed to a spuriously fiery show of bombast or bluster.

Similarly, the slow movements, Bartók's celebrated night musics and the andante passages (of which only the second movements of concerti 1 and 3 are examples: number 2 has a middle presto section) are treated with reflection in such a way that you realize how considered and measured, for all their excitement, the faster movements were. On the other hand, these musicians are not engaged in a superficial exercise of exposing contrasts for contrasts' sake. They get to the essence of the music. And they do so with great sensitivity… again, the perspicacity with which they negotiate the opening allegretto of the third concerto [tr.7], for instance, is more akin to reading a letter from Bartók to sympathetic listeners out loud, than parsing a press release by him.

Just as Bartók (1881-1945), we know, was conscious of the works in concerto form by Beethoven and Stravinsky, so, it's tempting to think that the highly enthusiastic phlegmatic (Mercurial, at times) Jean-Efflam Bavouzet gave a passing thought to emulating Bartók's own style of piano playing here – after all, the concerti were written for the composer himself to play. If that's the case, then the jollity, the regardful sense of fun (but never jocularity) in, say, the final allegro vivace of number 3 [tr.9] take on a new light. Perhaps Bavouzet is translating that letter. You certainly feel it was written to him personally.

The balance between piano and orchestra, and the placing of the percussion and timps (directly behind the piano itself in the first concerto), for example, are usually issues to be addressed with this repertoire. The piano should neither be a "showcase" instrument, as with Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff or Grieg, say; nor a "collaborator" as with Stravinsky or Shostakovich. Ultimately, for Bartók, it was a question of exploring textures, an opportunity to experiment with variety and variation. In that sense one plus one makes three. And that's exactly how Bavouzet, Noseda and the BBC Philharmonic approach these works… indeed, they seem concerned to suggest variety without implying that Bartók was ever anything other than focused and appropriately driven to a unified, though far from unique, vision. And just as concerned that such focus generates energy in the most appropriate ways.

The acoustic is up to Chandos' usual high standards, recorded at 24-bit/96kHz in studio at New Broadcasting House, Manchester, UK, on three days – presumably one for each concerto. It's supported by a clean and informative booklet. If you don't already have recordings of these key twentieth-century concerti, or want idiomatic, transparent and expressive ones, consider this set next.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.