The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

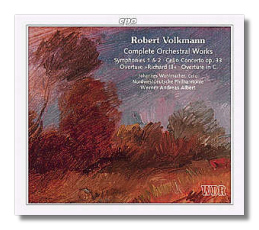

Robert Volkmann

Complete Orchestral Works

- Overture to Shakespeare's Tragedy "Richard II ", Op. 68

- Symphony #1 in D minor, Op. 44

- Symphony #2, Op. 53

- Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 33

- Overture in C Major, Op. posth.

Johannes Wohlmacher, cello

Norddeutsche Philharmonie/Werner Andreas Albert

CPO 999151-2 DDD 2CDs 50:21, 50:19

Robert Volkmann's name has been skulking round the history books for years, but little of his music has made it as far as the recording studio. But in the eyes of his contemporaries he was a figure of some standing, and this double-album of his orchestral music therefore deserves a generous welcome. It is billed as "The Complete Orchestral Music", which is true enough if you exclude the three serenades for strings, and I imagine that much of its its receiving its première recording.

In view of Volkmann's faded fame, I shall allow myself a short biographical outline. Friedrich Robert Volkmann was born in Lommatzsch, near Meissen, in April 1815 (a century and a day before Bille Holiday, as it happens), and studied first with his father and then with Carl Ferdinand Becker in Leipzig, where he made Schumann's acquaintance. After teaching in Prague (1839 - 41), he moved to Budapest where, but for a sojourn in Vienna (1854 - 58), he spent the rest of his days. Brahms and von Bülow were among his supporters (von Bülow and Liszt both performed his Piano Trio, and he was on good enough terms with the prickly Brahms for them to address each other as "Lieber Freund"). He was offered, and turned down, Bach's old job at St. Thomas' in Leipzig. His compositions were performed to acclaim across Europe, and he seemed to be on the way to Great Things - that never seemed to happen. Volkmann was not a very prolific composer in those pre-copyright days when quantity helped: though there are 71 opus numbers, most of his works are on a small scale; from the early 1870s, moreover, his urge to compose began to fall away, and not much more was to appear before his death in 1883.

Volkmann's Overture to Shakespeare's Tragedy 'Richard III ' is, as you might expect, a rather gloomy, forbidding affair, beginning low in the bassoons, bottom strings and trombone and never really brightening thereafter. Volkmann himself seems to have been in two minds about his intentions: Hilde Malcomess' notes quote him as denying that he was attempting "the musical depiction of external events", yet in a private letter he allies very precisely specific actions with musical gestures - an instance: "the […] double fortissimo B of the double-basses is supposed to represent the command to halt which Richard thunders at the pallbearers". Malcomess claims, indeed, that "The musical structure corresponds exactly to the action of the drama", though she doesn't give any musical or dramatic signposts to help the listener assess that statement. But it would help explain the episodic, patchwork nature of Volkmann's construction, even if it doesn't account for the unexpected appearance of the Scottish folktune "The Campbells are Coming" which bursts in towards the end of the piece and nips in and out of the textures on piccolo thereafter.

The opus number (68) of Richard III suggests it is a late work (Malcomess doesn't give a date, and my reference books are no more helpful), so the "Op. posth." designation of the Overture in C Major suggests that it is later still. Not so: it was written in 1863, first performed a year later, and merely published after Volkmann's death. It's less striking than Richard III - more competently made, perhaps, for the seams don't show as they do in the Shakespeare piece, but the music itself is not so striking, the material of a less ear-catching hue.

Volkmann's two symphonies stand in relation to the rest of his output and to each other rather as Brahms' do to his. Volkmann was all of 49 before he produced his First Symphony, composed in 1862 - 63, and Brahms 43 (thirteen years later). With both composers overcoming the psychological barriers to producing a symphony seems to have cleared the way for a second: Volkmann and Brahms both composed their second symphonies within a year of their firsts. And whereas each First Symphony is heavy, portentous, deeply serious in intent, each man's Second is optimistic and cheerful. It is difficult to avoid the old game of influence-spotting with Volkmann, though it sometimes redounds to Volkmann's benefit. The First Symphony opens with a heavy leitmotivic theme reminiscent of one in Borodin's Second Symphony - composed six years afterwards. Volkmann's Second has a theme that comes straight out of Taneyev's string quartets, which had decades to go before it was written. But there are obvious and genuine debts, to Beetboveh, hore end there to Berlioz (there's a recurrent bass figure in Richard III which is very close to one in Les Francs-juges), and pre-eminently to Schumann, whose orchestral style thoroughly informs Volkmann's - you can hear it as clear as you like in the horn-writing in particular. There are passages, too, where Brahms isn't too far away - but that raises the question of who influenced whom. The late English composer and writer Harold Truscott, an authority on Volkmann as on many other composers, maintained that Brahms' mature trio style was acquired from Volkmann, and it may well be true that Brahms learned from Volkmann's orchestral music, too. Ultimately, questions of style don't really matter; what does is how the music stands up among its mighty neighbours. There we see that Volkmann doesn't entirely come up to the same mark. The music doesn't quite sweep you off your feet the way theirs can, the tunes aren't quite as memorable, the working-out of the material that little bit less convincing. That said, he was obviously a man who had mastered his craft: the music is unquestionably well made, and he does some marvellous things with his material. A secondary figure, perhaps, but one whom deserves respect - and performances.

The work that will serve best as Volkmann's calling card is his Cello Concerto, Op. 33. Here again, there are obvious parallels with Schumann's concerto. Both works are in a single movement, both are in A minor, and both date from the early 1850s, Schumann's from 1850 itself and Volkmann's from 1853 to 1855; coincidentally, both composers were 40 when they completed their concertos. Volkmann's is a compact little masterpiece (it lasts a little over a quarter of an hour), perfectly matching material and structure. The tunes come tumbling out, one after the other, constantly engaging the ear. The world is not so stuffed with cello concertos of this calibre that soloists can go on ignoring it. It's been on CD before, on a Koch Schwann disc that repackaged an earlier (1984) LP coupling of the Volkmann and d'Albert cello concertos, but that recording doesn't seem to have made much of an impact. Let's hope this one wakes them up.

I have often found Werner Andreas Albert's conducting rather lacklustre in repertoire that I know, especially so in his woolly complete Korngold orchestral music; to be fair I have to say that in this unfamiliar music the performances struck me as being perfectly adequate. Johannes Wohlmacher puts heart, soul and elbow into the Cello Concerto.

I see that CPO are going back to Volkmann for the chamber music (with some of the string quartets and piano trios next due for release). I'll be going back for more.

Copyright © 1996, Martin Anderson