The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hovhaness Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

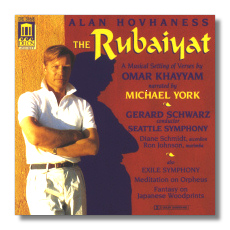

Alan Hovhaness

A Musical Setting of Verses By Omar Khayyam

- The Rubaiyat

- Symphony #1 "Exile Symphony"

- Meditation on Orpheus

- Fantasy on Japanese Woodprints

Michael York, speaker

Diane Schmidt, accordion

Ron Johnson, marimba

Seattle Symphony Orchestra/Gerard Schwarz

Delos DE3168

To paraphrase a favorite author: "Alan Hovhaness is either 80 years old and has written a million symphonies, or is a million years old and has written 80 symphonies." How many hundreds of opus numbers does Hovhaness have? Last time I checked, he had reached 53 symphonies, but it's only Saturday. Hovhaness is an original. You can peg the composer after a couple of bars. He invented an idiom all his own and furthermore continues to expand his technical resources. By all accounts, he composes blazingly fast, the route from brain to pencil point short indeed. A Hovhaness work gives you almost pure inspiration, without the effort or compositional struggle so apparent in the music of Schoenberg, Bartók, and Stravinsky. He makes it look so easy, and I envy him more than is good for me. On the other hand, inspiration really is with him "first thoughts," with disadvantages as well as benefits. At its best, the music is fresh and directly communicative, without the sense of "writing down." At less than that, one feels that Hovhaness has said it before and better.

Hovhaness is nothing if not sincere, sometimes to a fault. The Lady of Light cantata sets an embarrassingly purple text by the composer, often to music of great power. In The Rubaiyat, a melodrama, a speaker intones from the Fitzgerald translation, as the orchestra provides a Tiomkin background of orientalia which enhance the poems not a jot. On the other hand, Hovhaness provides beautiful interludes for orchestra and solo accordion. It's almost as if Hovhaness doesn't understand the poetry he sets. Based on other texts and other works, I fail to see what the composer has in common with the poet's nihilistic hedonism or what in the verses impelled the composer to write the music. Nevertheless, the performance betters André Kostelanetz's première recording all the way around: Schwarz's Seattle troops give the composer some choice moments; Michael York is a finer reader of poetry than Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (who tended to sound like a knock-off Ronald Coleman); Diane Schmidt's accordion soars like Shaham's Strad.

However, the Symphony #1 shows the Rubaiyat for the minor work it really is. Hovhaness wrote it as an artistic response to the 20th-century genocide of the Armenians by the Turks. The events changed Hovhaness the composer from "the American Sibelius" (as newspapers dubbed him for his early works, since withdrawn) to the "sweet singer" of Armenia. Much as Ernest Bloch is linked to 20th-century Judaism, so Hovhaness and Armenia have locked together. Also like Bloch, Hovhaness very rarely uses "authentic" melodies and prefers to invent his own. The Armenian diaspora has produced many composers, but most of these have adopted international or country-of-residence styles. I fail to see anything specifically Armenian in Khachaturian, for example. Hovhaness is one of the very few who tries to express Armenia's heart.

The style is primarily tonal, even modal. Techniques range from rhythmically free heterophony, baroque counterpoint, chorales, chant, and Hovhaness' very own inventions, the "spirit murmur" being the best-known of these. In the late 30s, the symphony must have struck its first hearers as something from Mars, as it bore no relation to any current strain of modernism - no post-Romantic sweeps and swoops, no systematic filling-in of notes à la Schoenberg, no Cubist skew of musical language as in Stravinsky and Copland, no back-to-Bach, no Satie-like adaptations as in Thomson. Bartók's invigorating modernism through folk sources haunted regions other than Armenia. Hovhaness had invented a fresh musical idiom and without a predecessor (or at least anyone I know about). From the opening notes, we enter a strange emotional landscape - deliberately archaic, distant and distancing - as clarinet and flute take up a chant, interrupted violently by the larger orchestra. The music is spare, the textures clear. This movement does not develop, as the Austro-Germanic symphony would. Elements are stated, repeated, and recombined in a readily-comprehensible way, due in no small part to Hovhaness' skill in devising memorable gestures. For me, the chant is a lament, the interruptions rages against violence, but the strangest thing of all is the restraint. Hovhaness doesn't sob or gnash his teeth, and thus imparts an awesome power. The second movement is beautiful and sweet as a really good drink of water. Again, the means are simple, and all depends on the quality of the melodic goods before you. Lou Harrison has called Hovhaness a "melodist that comes along once every 100 years," and I have trouble disagreeing as I listen. However, one says such a thing only under enchantment. It doesn't survive two seconds of thought. The last movement builds on an original chorale, climaxing in a fugue on and grand restatement of the chorale (although the ending is an incredible, poetic surprise). For me, it expresses the endurance of the Armenians.

Meditation on Orpheus has had several recordings, and deservedly so. Hovhaness presents it as an abstract retelling of the Orpheus myth, as opposed to a Strauss-like orchestral incarnation of the drama: the loss and lament for Eurydice, the descent into Hades, the winning and second loss of Eurydice, and the rending of the singer at the hands of the Bacchantes. Again, you won't find Brahmsian development, but the piece hangs together nevertheless. I doubt this is something that you can analyze in the score. On the other hand, many a work that appears bolted and riveted on paper can seem much more capricious to the ear. Hovhaness at his best tunes into the inner tides of his audience unlike few contemporary composers.

I have no idea of Japanese music (other than Takemitsu film scores), but the Fantasy on Japanese Woodprints certainly sounds Japanese to me. As a matter of fact, my wife, on coming into the room, asked me out of the blue if the composer was Japanese. It may be a matter of musical iconography: flutes, drums, and the wooden bars of the marimba. After all, there's a passage of pure baroque sequence in the work, and the melodic ideas seem close to the "Armenian" works as well. The work, among other things, is a study in rhythm, and Schwarz and the Seattle give the piece the clean articulation it needs.

Praise to Gerard Schwarz for yet another disc of interesting, off-beat American repertoire played with serious care and, at times, devotion.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz