The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

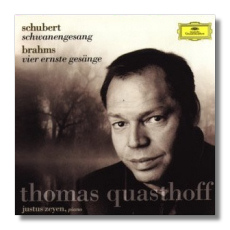

Schubert / Brahms

Lieder Cycles

- Franz Schubert: Schwanengesang

- Johannes Brahms: Vier ernste Gesänge

Thomas Quasthoff, baritone

Justus Zeyen, piano

Deutsche Grammophon 471020-2 65:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: Ne plus ultra.

Schubert wrote the songs of Schwanengesang ("swan-song") in his last year. Most of the poems come from Heine or from Rellstab. Rellstab had created the texts for Beethoven. At Beethoven's death, Schindler passed them on to Schubert. Schubert himself grouped these songs together, although it was the publisher, rather than the composer, who gave them the title and added a poem by the distinctly minor Seidl. The title goes back to the notion, probably as old as Herodotus, that the swan, before it dies, sings the most beautiful song. Whoever came up with this fancy probably never saw a swan up close. At any rate, it now means the final work of an artist.

It turns out that this collection – not really a cycle as Beethoven and Schubert had defined the genre – contains some very beautiful songs indeed, almost all of them breaking expressive new ground. If I recognize Winterreise as Schubert's greatest song-cycle, I nevertheless love the looser Schwanengesang more. It probably comes down to a matter of preferring these tunes and harmonies over the others.

When I read about Schubert's songs, I usually get analyses of poems and, if lucky, how certain emotional points in the poems find interpretive echoes in the music. However, I've found very little on the music itself. As I listened to the CD, the composing details impressed me as they hadn't previously. The accompaniments show a high amount of variety and invention, as well as Schubert's ability to find different emotional contexts for the same device. In "Liebesbotschaft," for example, the arpeggio conveys ardor and a rushing brook. In "Die Stadt," it evokes ill spirits flitting through the air, sort of a soundtrack for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Unlike Die schoene Muellerin, where every song but one is strophic (different stanzas of the poem share the same music), every song here (with maybe two exceptions) is through-composed. Even a song like "Ständchen" ("Leise flehen meine Lieder") gives the final verse a different tag. In this set, Schubert decisively redefines what a song could be. A composer like Zeller, for example, who set many of the same texts as Schubert, never breaks strophic form, because to him a song is indeed strophic. The composer's job becomes, in this case, to find a single musical stanza that suits all the verse stanzas. Schubert habit of through-composing has the obvious ability to follow the poet's turns of thought more closely, but it has a potential disadvantage as well. Since the listener never knows where the line is going, Schubert can lose him. Indeed, early listeners found Schubert's songs difficult for exactly that reason. Now, of course, we delight in the uncertainty. It keeps our interest.

The Rellstab texts are far more conventional than the Heine. The images never stray from their early German Romantic flock. The streams are always "rushing," that old devil "longing" gives the poet fits in his "Herz" or "Brust," and so on. It amazes me that Schubert comes up with such great things for such stale words, but of course they weren't stale when he worked with them. Still, in attitude, the songs don't differ all that much from the songs to the Wilhelm Müller cycles. The Heine, however, signals greater psychological complexity and unease, and unusual words creep into the poetry. Even the relatively conventional love-song "Fischermädchen" (more accurately, a seduction song) eschews easy vocabulary. One looks in vain for "tears," "breast," and so on. We get the almost-technical "Horizonte" (horizon) rather than the conventional "in der Ferne," the Romantic cliché for the same thing. In the Heine settings, Schubert's musical imagery becomes wilder, even less predictable. You won't hear songs so savage, so volatile, and so free in their rhetorical movement until Mussorgsky and Mahler. Given the quality of texts and the dramatic power of the rest of the collection, people have wondered what on earth prompted the publisher to append Seidl's very silly "Taubenpost" ("Pigeon-Post") to the end, particularly since it follows the harrowing "Doppelgänger." I offer one explanation. There are seven Rellstab songs, grouped together, the six songs that comprise the Heine group, and "Die Taubenpost." The Rellstab group ends with "In der Ferne" and "Abschied." In short, a highly dramatic song, followed by something comparatively light. Furthermore, "Abschied" and "Taubenpost" have fundamentally the same rhythm and character. I suspect the publisher included "Taubenpost" for reasons of structural symmetry – to manufacture design where there really wasn't any. The end of the Rellstab songs show that Schubert had no qualms about the conflicting tone, so why not repeat? Also, despite the silliness of the text, "Die Taubenpost" is one great song, and it closes the collection on an upbeat. Ending on "Der Doppelgänger," you might as well take a gun and shoot yourself.

As magnificent as they are, the Brahms songs, written seventy years later to texts from the Bible and the Apocrypha, are fundamentally more conservative. Brahms wrote them close to the end of his life, probably as a memorial to close friends who had recently died or were gravely ill, including Clara Schumann, Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, Hans von Bülow, and Theodor Billroth. Brahms chose powerful texts – all to some extent mediations on death – and set them to powerful music. As far as their construction goes, they show the same habits of large-scale structural thinking as the final orchestral and chamber music. If you think about these "serious songs," they are all fairly sectional, like the Schubert "Der Atlas," but where Schubert makes the musical equivalent of jump cuts, Brahms carefully smoothes things over. For some strange reason, with the exception of this set, I rarely encounter Brahms' songs live, and he wrote a ton of great ones. Surely fewer people know, say, the "Sapphic Ode" than "An die Musik."

Both sets of songs are "bigger" somehow than most Lieder. Schwanengesang in particular takes a great interpreter just to keep up. I heard Hermann Prey do these in recital roughly thirty years ago – a tremendous performance that nevertheless didn't quite reach the mark of the songs. For years, my standard has been Fischer-Dieskau and Moore on stereo EMI, which I don't believe has made it to CD. I would characterize this account as dramatic, wonderfully variegated, and "considered." Quasthoff works at this level. He has the variety of tone-color the songs demand (Prey's major shortcoming), and obviously he's thought about things. Nevertheless, he comes across as spontaneous and yields nothing in drama to his predecessor. The difference between Fischer-Dieskau and Quasthoff is the difference between Olivier and Paul Newman. The fundamental difference gets down to the fundamental character of their voices: Fischer-Dieskau, lighter and brighter, more piercing; Quasthoff, mellower and richer. Fischer-Dieskau's is a somewhat "Expressionist" performance: the grotesque is more grotesque, the stabs of pain sharper, the moments of tenderness filled with tears. Quasthoff, in comparison, comes off as a man with a weight of experience behind him – a little like Wotan in Götterdämmerung. I must also say that the collaboration between Quasthoff and pianist Justus Zeyen surpasses that of Fischer-Dieskau and any of his partners, including Gerald Moore. For one thing, it's a partnership of equals. One never senses that either singer or pianist drives the performance. They seem of one mind. Above all, they appear to make it up on the spot, even though you know that can't be true. They achieve the spontaneity without sacrificing near-microscopic detail.

I studied the Brahms songs in college and found them a bear to sing, particularly the final one, "Wenn ich mit Menschen- und mit Engelszungen redete" ("though I speak with the tongues of men and angels"), with its call for rich, mellow tone at the upper end of the baritone range. So Quasthoff's apparent ease in the most difficult passages impressed me no end, as did, of course, his ability to convey the beauty and power of the texts.

In short, at full price, this CD's a bargain.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz