The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

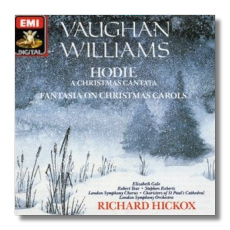

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Christmas Music

- Fantasia on Christmas Carols

- Cantata "Hodie"

Elizabeth Gale, mezzo-soprano

Robert Tear, tenor

Stephen Roberts, baritone

London Symphony Chorus

Choristers of St. Paul's Cathedral

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

EMI 54128

Summary for the Busy Executive: Two favorite pieces, lovingly performed.

In the 1950s, British critics began to divide British music into two opposite camps: Vaughan Williams and Britten. Some of the oppositions set up include "parochial" vs. "international," "pastoral" or "idyllic" vs. "psychological," "amateur" vs. "professional," all to Vaughan Williams' detriment. To be a card-carrying member of either camp, you had to foresake the other – a religious sectarianism. Between the publication of Michael Kennedy's The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (1964) and Alain Frogley's Vaughan Williams Studies (1996), not one major critical study appeared, and I suspect not very many doctoral dissertations took up his music. No one seems to love Vaughan Williams but people. Until very recently, he has remained irrelevant or, worse, the Symbol of Everything Wrong in critical discussions of British music. I don't pretend to know the ins and outs of what was going on, but it probably wasn't pure aesthetics. The characterizations are too polemical and, like most polemics, nowhere close to a just assessment or even to superficial facts. Britten, unquestionably a great composer, was elevated to Greatest English Composer since Purcell (a phrase written more than once), writers conveniently forgetting not only Vaughan Williams but Elgar, Walton, and Tippett. As late as 1994 (and really echoing sentiments written 20 years earlier), Ned Rorem makes this and several similar claims for Britten. It is a fact that neither Vaughan Williams nor Britten particularly liked one another's music, although Vaughan Williams recognized immediately the stature of Peter Grimes. Fortunately, their quirks needn't apply to the rest of us. However, the similarities of their music and artistic careers strike me more forcibly than the differences: the emphasis on vocal and choral music, the thorough professionalism, the looking to the Continent (France especially) for hints on how to proceed, the deep spiritual nationalism and inspiration from the British past, particularly through British literature, the fascination with Purcell and the Tudor madrigalists, and the fact that Christmas, close as I write this, inspired some of their best work.

The Fantasia on Christmas Carols comes from 1912, close to the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis and the Five Mystical Songs. Unlike the Tallis Fantasia, it exhibits the structural laxity we expect in fantasias. Vaughan Williams builds the work out of mainly four traditional carols – "The truth sent from above," "Come all you worthy gentlemen," "On Christmas night," and "There is a fountain" – none of them particularly well-known even now, and weaves in the more familiar "The First Nowell," "The Wassail Bough," and "A Virgin Unspotted." The four main carols appear mainly one after the other. Vaughan Williams has written about this kind of piece in his and others' output in the folk-song revival that the composers grew so enthusiastic about the tunes they found that they wanted to give the melodies back to the widest possible audience in close to a "pure" form. Vaughan Williams would produce these kinds of pieces throughout his career. To a great extent, the beauty of the piece depends on the beauties of the chosen tunes, as much as on the craft of the composer. "The truth sent from above," in particular, will haunt you. However, it would be a great mistake to see Vaughan Williams' contributions as just a string of melodies. First, the arrangements themselves contribute to the effect – they set off the tunes as a ring of small diamonds deepens the color of a central sapphire. For example, the piece opens with a gorgeous solo cello meditation on "The truth sent from above," before the baritone solo and, later, the choir join in. The composer also specifies "colors" for the choir: singing the words, singing with closed lips, singing "ah," and singing with half-closed lips on a short "u" (as in "but"), habits of choral thinking he might have picked up from his studies with Ravel. Furthermore, no matter how loose a Vaughan Williams piece might appear to the analyst, this is the work of a considerable symphonist. The Fantasia coheres "psychologically" – slow introduction, allegro somewhat related to the slow part, the allegro's "B" section marked by a change to triple time, and a slow coda based on the allegro theme. On the page, it's not all so "hard and fast," but it chimes right to the ear, particularly the change to the "B" section. What seems a major mis-step on the page thrills the soul in performance, as if, at night, one suddenly became aware of the brilliance of the stars.

This recording seems to be EMI's replacement of two classic performances: the Fantasia, led by Barry Rose, and Hodie, performed by Janet Baker, Richard Lewis, and John Shirley-Quirk (all in their glorious prime) and conducted by David Willcocks. In the Fantasia, baritone soloist Stephen Roberts has a much lighter voice than Rose's soloist, John Barrow – in fact, it sounds light enough for a lyric tenor. I prefer Barrow. However, Hickox has it all over Rose with choral and instrumental clarity, particularly in the strings. I hear subsidiary lines in Hickox I never knew were there, and, since they sing carols other than the ones you hear the words to, it's important to the appreciation of Vaughan Williams' art. Choral diction is superb. You don't need liner notes to understand the words.

According to Michael Kennedy, Hodie, Vaughan Williams' last major choral work, was also the first one in which hostile criticism openly surfaced and the pro-Britten camp marched out into the open. Donald Mitchell wrote, among other things:

… grossly over-praised and grossly under-composed…. If this is the kind of music that rouses cries of exaltation, then our musical culture is in a worse condition than I thought possible. Of course, a good deal of the whooping is positively Pavlovian…. There is a level below which "directness" and "forthrightness" of utterance – qualities for which Vaughan Williams is praised – deteriorate into a downright unacceptable and damaging primitivity…. It is double damaging when his contemporaries are so blind (or deaf, perhaps) that they mistake patent coarseness as evidence of exuberant genius….

Unsatisfied with that and determined to put Vaughan Williams' critical rep in a coffin and drive in the nails, Mitchell followed up with an attack on Vaughan Williams' recent collection of essays. Fastening on to the composer's half-joking references to his "amateurish technique," Mitchell wrote:

It has to be admitted that this self-criticism has more than a grain of uncomfortable truth to it. When listening to a work of the character of Hodie, where, I suspect, Vaughan Williams' compositional conscience was at a low ebb, it suddenly becomes very noticeable how clumsy his technique can be, and how much he relies on his inimitable idiosyncrasies to pull him through. At the same time, one is reminded, rather disturbingly, of many a more masterful composition of his where his technique has not seemed fully adequate to his needs.

What is suspect about Mitchell's criticism is how unspecific it is. What is not said is, "All cultivated musicians know what these deficiencies are. It is better to pass over them in silence." Yet that is precisely what a critic can't do. Since it is neither right nor wrong, a judgement – or, less exaltedly, an opinion – is only as good as its support. Mitchell supplies none. Even more disturbing, nobody seems to have called him on it. Hodie, according to Mitchell, is "grossly under-composed." Which parts? How can a piece be undercomposed? Give an example of "clumsy technique." What are the "inimitable idiosyncrasies" that pull VW through? If they pull him through, does this means that the piece succeeds? If not, why not? In what "greater" composition has his technique not met his needs? What are the needs of that composition? How hasn't he met them? And so on. One cannot really answer these charges, since Mitchell has provided nothing substantive to hold them up.

On the other hand, one can supply many examples of brilliance and inspiration at high heat from Hodie, not the least of which is the syncopation of the opening, as the chorus jubilates to "Nowell! Nowell! Hodie Christus natus est." The composer joked that if he had known he was going to conduct it, he would have made the rhythms easier. "Bright portals of the sky" shows us the stars, planets, and galactic fires scintillating like jewels, in orchestration both brilliant and belonging only to the composer. "The March of the Three Kings" pits chorus and orchestra in what amounts to two different meters, with an ostinato-like bass setting off different rhythmic facets of the main tune. It's also a lesson in how to handle large forces – symphony orchestra, chorus, and soloists – with stunning clarity. That alone to me refutes the charge of "no craft." But, wait! There's more! Vaughan Williams sets Hardy's "The Oxen" and Milton's "Hymn on the Morning of Christ's Nativity" simply better than anyone else. The "Hymn" in particular would give most composers fits, due to its irregular meter. Surprisingly, Vaughan Williams doesn't regularize the meter, but emphasizes its quirks – in its first appearance for solo mezzo, ravishing and rapturous; in its second for full forces, with great energy. There's also a quasi-recitative for boys choir, which at first seems to haul out yet again Vaughan Williams' pentatonic manner (think of the black keys of the piano), but which transforms into a modally-inflected chromaticism, with hints of the octotonic scale (formed by alternating whole and half-steps, or half- and whole steps). I have no idea what Mitchell means.

Again, Hickox's chorus and orchestra surpass those led by Willcocks. Rhythms are sharp and textures much clearer. The long crescendo and build-up in "The March of the Three Kings" comes off more purposefully in the Hickox, who builds a beautiful arch to the climax. I'd even rate the male soloists as better singers than Willcocks's stars, although Lewis has a larger voice than Tear and Shirley-Quirk has more weight in his tone than Roberts. Phrasing and diction – the mark of a singer who knows his business – are much better in the younger men, particularly Roberts, who comes across as unaffectedly as a great pop singer. However, Willcocks has Janet Baker – the great British singer after Ferrier. Elizabeth Gale is very fine indeed, but she competes with a legend. The Willcocks – if you can find it (EMI CDM769872-2) – is worth getting for Baker alone. The voice, clear as silver, radiant as Spring, melts the stoniest heart. It lets you feel the ecstasy of mysticism. I would go with her "into the gloom, hoping it might be so." It does no harm to have both performances.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz