The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

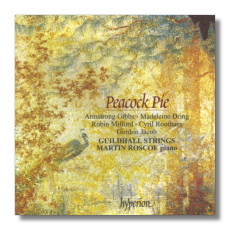

Peacock Pie

- Gordon Jacob (1895-1984): Concertino for Piano & String Orchestra

- Armstrong Gibbs (1889-1960): Concertino for Piano & String Orchestra, Op. 103

- Cyril Rootham (1875-1938): Miniature Suite for String Orchestra & Piano

- Robin Milford (1903-1959): Concertino in E Major for Piano & String Orchestra

- Armstrong Gibbs: Suite "Peacock Pie" for String Orchestra & Piano

- Madeleine Dring (1923-1977): Festival Scherzo for Piano & Strings

Martin Roscoe, piano

Guildhall Strings

Hyperion CDA67316 DDD 60:14

Summary for the Busy Executive: Cary Grant should be this charming.

The English and the French, contrary in so many other ways, both excel in what's called light music, or light symphonic music – more so than Americans, at any rate. I say this after just completing marathon listening sessions of Leroy Anderson and Don Gillis, two American masters of the genre. I suspect that most American energy goes into pop instead. What distinguishes the English and French is that they haven't the attitude of "it's just light music, mere fun." For fun – as a subset of happiness – is actually a big deal, nothing mere about it. It's hard to have genuine fun, and we observe a desperate search among the often-expensive products of a huge industry dedicated to manufacturing a good time. Most of us get way too serious about having fun, like the kid who makes himself sick or upset anticipating some treat. I relate British distinction in light music to an attraction to understatement and to its converse: a disdain for emotional inflation, pomposity, and "side."

Almost all these works – like the Bloch first concerto grosso, incidentally – were aimed at school orchestras, institutions stronger and far more numerous in Britain than in the States, fronted by professional-caliber soloists. Excepting the marching band (spectacle for the all-important high-school football game), the U.S. of A. has largely given up as extravagant frippery music education in public schools. Beyond their pedagogical utility, however, a small string orchestra combines with piano rather attractively. One can see an affinity with the piano quintet, and indeed some of these works exist in smaller versions. Although many of these composers successfully worked in more extended forms, here they become miniaturists. Some people deride the miniaturist as beneath the symphonist, but really the two genres require different skills. The symphonist needs to maintain interest over the long haul. The miniaturist needs to keep interest at all times, and it's the rare composer who can do both. The symphonist deals in greater complexity; the miniaturist in white-hot inspiration. All the composers here came under the orbits of Vaughan Williams and Holst, particularly the folk-music side of things. Jacob, Milford, Gibbs, and Dring all studied with RVW, while Rootham's Miniature Suite shows the obvious influence of Holst's St. Paul's Suite for strings.

Cyril Rootham, born three years after Vaughan Williams, died before the Munich Agreement and the Second World War. The music sounds like early Vaughan Williams "folk," akin to the older composer's In the Fen Country – on the verge of something startlingly original without quite breaking through. For me, the third-movement scherzo holds the most interest. It manages to beat five without calling attention to the fact, a beautiful example of the art that hides art.

Gordon Jacob firmly steps into the modern era. His music speaks in a personal, neoclassically-influenced idiom but of Romantic attitudes, very similar to something like Holst's Fugal Concerto. His superb technique has, for many critics, overshadowed his substance. He seems one of those composers who can do anything he wants, as shown by his Concerto for Piano Duet (3 Hands), written for the team Phyllis Sellick and Cyril Smith, the latter of whom had lost the use of his left arm, due to a cerebral hemorrhage. One senses no struggling in Jacob's work, which leads many to underestimate him. He composed well into his eighties vital, vigorous music, but only the "light" pieces (and his orchestrations of others' work) seem to receive recordings. In his catalogue one finds at least two symphonies and any number of major pieces, none of which are all that well known. Jacob writes cleanly and directly at all times, with no use at all for emotional inflation. Some may find him reserved. To me, he's a plain speaker, in the sense that Lincoln was. The most tightly-written piece on the program, Concertino shows all his virtues. It glitters like a hummingbird's throat.

Robin Milford suffered from major depression for much of his life. He attempted suicide at least twice, finally succeeding with an aspirin overdose in 1959. However, excepting a couple of blocked years, he composed steadily through his illness. You'd never know his mental state from the work here. This is the program item most directly touched by Vaughan Williams' folk-song example. Indeed, the first theme begins like "The Springtime of the Year," before it settles into mini-development, proving that the composers of the English folk-song school didn't simply arrange traditional tunes. The slow second movement, "Romanza," begins almost like a salon waltz, but quickly reveals unexpected intensity. The finale moves with Mozartean litheness. Why did a fellow who could do that have to kill himself?

Cecil Armstrong Gibbs lives on in his songs, if in practically nothing else. His "By a Bier-Side" has deservedly become a classic of the English art song. The composer felt especially drawn to the poetry of Walter de la Mare, whose work exemplifies in literary form the strengths of British light music: a beautiful, even magical surface and a brief glimpse at great depths. The work of de la Mare captures the music from under the hill. Gibbs's Peacock Pie (the title itself and the movement headings come from the de la Mare collection). It's a piece that delights mainly from the surface. The later Concertino, on the other, while yielding nothing to its predecessor, to me renders more completely de la Mare's world. In its brief span, particularly in its first movement, it hints at unsettling power and a disturbing beauty, all without having to resort to mammoth means or proportions.

Madeleine Dring – pianist, composer, and actress – died all too young in her fifties of a cerebral hemorrhage. She scored plays and television programs and confined herself mainly to light pieces, like the Festival Scherzo. The work is an unashamed romp in driving triplets, without feeling the need to be anything more. It's like savoring a perfect piece of chocolate after a particularly satisfying meal. It's also yet another beautifully-crafted piece, of high inspiration throughout.

Roscoe and the Guildhall Strings dazzle. For my money, this is one of Hyperion's great CDs. Roscoe treads the fine line of light, stepping into profound when he needs to. The Guildhall amaze me – even more than the Orpheus does – with the richness of their collective interpretation. I can't recommend this disc highly enough.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz