The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Modern Masterpieces for the Viola

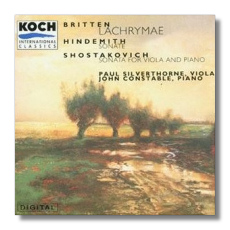

- Benjamin Britten: Lachrymae

- Paul Hindemith: Sonate, Op. 11/4

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Sonata for Viola and Piano

Paul Silverthorne, viola

John Constable, piano

Koch 3-7270-2 66:46

Summary for the Busy Executive: Wonderful

The sound of the viola has always attracted me more than that of the violin, which tends to squeak, rather than speak, to me. Honestly, I've never seen the justness of viola jokes, although I've certainly understood them. However, really great players seem few and far between, and the instrument demands from composers ideas of real quality, since they can't resort to the cheap thrill of playing in the violin's stratosphere. The viola sounds best in the middle, absolutely duck soup to a composer fond of middle sonorities, like Brahms or Shostakovich. The instrument's "personality" puts me in mind of a writer like William Stafford, slipping in beautiful music among apparent plain speech and common sense. There's very little nonsense or flash among the best literature for the instrument.

I've never heard a better violist than Paul Silverthorne, and that includes any well-known great player you care to mention. I first encountered him as the soloist in Rózsa's viola concerto (Koch 3-7304-2H1), where he blew me away with his dark, brooding tone in a dark, brooding work. I then heard him in the Brahms sonatas (Meridian CDE84190) – again, highly Romantic works suited to his rich sound. Most of the works here call for something wirier, drier. I wanted to know the accommodation, if any, Silverthorne would make or whether he would force these pieces into what I regarded as his style. I shouldn't have worried. Silverthorne adapts to the character of the music. Above all, he is a superb chamber-music partner. All these performances sound like the conversation of equals. Neither Silverthorne nor his extremely subtle accompanist, John Constable, dominate, and in these works, that's as it should be.

Like his teacher Frank Bridge, Britten was a violist, although he never played it in public. Indeed, the Lachrymae is his only work featuring viola as principal soloist (the early Double Concerto for violin and viola has, of course, two soloists). Toward the end of his life, he arranged the Lachrymae for soloist and string orchestra as a favor to Cecil Aronowitz. The title comes from Dowland, one of Britten's two main Elizabethan inspirations (Wilbye was the other). In this, Britten continues the threads inaugurated by the composers of the New English Renaissance, particularly Holst and Vaughan Williams. Britten hadn't much use for Vaughan Williams' music, although he recognized him as an important English figure, just as Vaughan Williams had little sympathy for Britten's, although he regarded Peter Grimes as a major achievement. Furthermore, the differences between the two's Elizabethan interests strike me as significant. Vaughan Williams was more attracted to the sacred music – composers like Tallis, Byrd, and Weelkes – which he considered founded on folk music. Britten, although he used and arranged folk tunes, never bought into the intellectual background of the British folk-song revival and found Tudor secular music a far more fruitful and cosmopolitan inspiration, particularly the ayre and lute-song. Britten built the Lachrymae as variations on a Dowland song. Dowland, of course, had written seven lute fantasias based on his song "Break now, my heart, and die" under the title Lacrimae, or Seven Teares. Britten uses another Dowland song, "If my complaints could passions move," as the basis of his variations. Furthermore, one never hears the theme in its entirety. The work begins in thematic "clouds," which gradually coalesce into the first variation. One hears the fullest statement of the Dowland song, with its original harmonies, at the end. From here to there, one goes through some witty and even moving variations, including a march, a scherzo, and a wistful little waltz. The texture, however, is fairly spare, and Silverthorne and Constable stress its clarity and the rhythmic articulation.

Hindemith almost single-handedly revived the viola as a solo instrument (violist Lionel Tertis in England also helped), both as a virtuoso performer and as a composer. He wrote at least three concertos for the instrument, four sonatas for viola alone, and three sonatas, among many other pieces. This sonata dates from 1919, while the composer was still really a late-Romantic composer. To those familiar with Hindemith's mature style, the opening movement will probably come as a shock – a beautifully lyric Brahmsian allegretto with an harmonic fluidity reminiscent of Reger. Stemming from Reger as well are Hindemith's ideas at this time on counterpoint and on the emphasis on variation form. The last two movements are theme and variation form, with a fugue crowning the variations of the second movement. One also hears thematic links among all three movements. The sonata doesn't move like Hindemith's mature work, where counterpoint essentially intensifies the rhythm. It's more like Reger – commenting on melodic ideas. Nevertheless, one can't really call the sonata "lush." Hindemith keeps a tight rein on the number of voices heard at once and on the "spacing" of the voices. Still, Silverthorne sings more warmly here than in the Britten, as he should.

The Shostakovich sonata stands as the composer's last major work. The symphonies, of course, have many wonderful passages for the viola (I think particularly of the last movement of the thirteenth, "Babi Yar"). The sonata typifies Shostakovich's bleak late music. I know these works put some people off, with their small gestures frequently repeated, but for me it's the apex of the composer's catalogue. At over half an hour, the sonata is by far the most substantial work on the CD, for my money the finest thing ever written especially for the viola (Brahms originally composed his sonatas for clarinet). The music is pared to the bone, both in terms of texture and the number of ideas. Most of the themes are based on the interval of the falling or rising fourth. The opening, barely a whisper on the viola's open strings, gradually becomes a savage marche macabre, requiring an almost imperceptible build from both violist and pianist. Silverthorne is especially effective here, eliciting from his viola both a taut, inward thread of sound and a cry of rage. Furthermore, you find yourself in the middle of that cry, with little idea of how you were moved there. The second movement works the usual Shostakovich klezmerian allegretto, such as we find in many of the string quartets. The finale, a huge adagio dedicated "in memory of the great Beethoven," uses the late Shostakovich device of Famous Quotation ("William Tell" overture in the fifteenth symphony, for example), here the first movement of Beethoven's "Moonlight" sonata. The quotes stand as enigmas, particularly since Shostakovich's emotional context for the quote lies worlds away from Beethoven's. They provoke metaphysical questions that can't really be answered, although they do shed musical light on Shostakovich's body of work. Once it hits you, you stand amazed at how often you encounter these ideas, only slightly disguised, in pieces throughout Shostakovich's career. I haven't yet worked out this particular quotation, but the rhythm of the "William Tell-Lone Ranger" theme, for example, pops up in quite a few symphonies and concerti, very often in close proximity to the famous "DSCH" musical signature. Metaphysically or psychologically I have little idea what the association means, but they sure do fit together musically. Furthermore, the adagio presents the violist and pianist with a tour de force: fourteen minutes of slow playing at a dynamic range restricted mostly to soft. Both Silverthorne and Constable seldom reach even a mezzo-forte, and yet the viola's singing line has deep contour and shade, with again a great variety of tone color from both players.

As far as their respective musical emotional worlds go, I can think of few composers further away from Beethoven than Shostakovich: one essentially heroic in expression, the other essentially neurotic. Beethoven may have experienced personal pain, but it almost never comes out in his music. Even the funeral march of the "Eroica" sings a dignified, noble, indeed public grief, rather than a messy personal one. On the other hand, as far as their composing goes, they're fairly close. Both are masters of economy and directness: with both, one idea can change the world, usually rather dramatically. Incidentally, Beethoven admired this same quality in Handel, whom he thought of as his master in this regard. Nevertheless, Beethoven stands much closer to Handel than to Shostakovich. Shostakovich's quote presents Beethoven in a fun-house mirror. Where Beethoven is serene, Shostakovich is fairly bleak, and in many ways it comes down to his change of Beethoven's underlying triplets to straight eighths. Some writers have seen hope in the last measures, but I disagree. There is indeed a slight leavening of the gloom, but it's too little, too late. It reminds me very much of the wan smile at the end of one of Sholem Aleichem's Tevye stories: "But it's time to talk of cheerier things. Have you heard about the cholera in Odessa?"

Both Silverthorne and Constable set a very high standard in all these works. As I've said before, Silverthorne makes the viola exciting to listen to – a rare ability. They're the best I've heard in both the Britten and the Hindemith, but then again I've not heard all that many different performances (Bashmet, Kashkashian, Golani for the Britten and the Hindemith). I prefer them to Hillyer and de Leeuw (also on Koch) and think them the equal of Bashmet and Richter (on MK) in the Shostakovich.

The sound is fine.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz