The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schumann Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

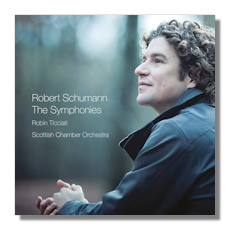

Robert Schumann

The Symphonies

- Symphony #1 in B Flat Major "Spring", Op. 38

- Symphony #2 in C Major, Op. 61

- Symphony #3 in E Flat Major "Rhenish", Op. 97

- Symphony #4 in D minor, Op. 120 (1851 Version)

Scottish Chamber Orchestra/Robin Ticciati

Linn CKR450 2CDs 2:13:15

Also available on Linn SACD CKD450: Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

Robert Schumann was supposedly a bad orchestrator. After all, a fair number of musicologists have made the charge over the years, and so it must be true. Right? Actually, Schumann wasn't a bad orchestrator at all. Orchestration may not have been his strong point as it was at the time for Hector Berlioz, but neither was it a calling card for Beethoven or Brahms. Leonard Bernstein famously made disparaging remarks about Beethoven's orchestration, and others have suggested that Brahms' ability as an orchestrator was questionable, citing in particular the opening of his D minor piano concerto. But the fact is, these composers generally attained the sound they wanted from the orchestra and were quite competent at orchestration. So, let's put the judgment about Schumann to rest: the charge that he was a bad orchestrator is unfair, if not totally untrue.

More and more today, we recognize this fact, not least because of recordings of his symphonies like these by young British conductor Robin Ticciati. He typically delineates orchestral textures with his deft skill to attain proper instrumental balances and to draw out meaningful detail from his players that you might not notice in other performances, especially from those in decades past, when larger ensembles were led in these symphonies by epic-minded conductors. Indeed, Ticciati's Scottish Chamber Orchestra is about the same sized ensemble used in Schumann's time (32 strings; and under 60 players total), and we thus hear the various instrumental forces more transparently, the way Schumann wanted the listener to hear them.

But clarifying Schumann is hardly the only issue: his music here can be epic without sounding bloated or bombastic or without coming across as lacking subtlety and panache. Thus, the "Rhenish" Symphony can be heroic and big while still having a relatively lean sound. Ticciati and company convey not only an all-conquering character here but a multi-faceted work whose joy and positive resolve belie the composer's mental and physical struggles throughout much of his adult life. The fourth movement is brilliantly rendered here in its mixture of the stately and grim, and the finale may be one of the best performances ever recorded: the somewhat understated opening is utterly charming and the rest is buoyant, sunlit and triumphant, never sounding bombastic as in many other performances.

By coincidence I had just listened to Christian Thielemann's DG recording of the "Rhenish" from 1998 before auditioning Ticciati's, and by comparison the newer effort was vastly more effective in its leaner sonorities and fleeter tempos. Thielemann, especially in his recent work, impresses me as a fine, if somewhat eccentric interpreter. Yet, his Schumann "Rhenish" was almost boring, at least alongside Ticciati's account. Ticciati's tempos are fairly centrist but the playing is always very spirited and vital.

Throughout the cycle, in fact, the pacing is moderate, sometimes perhaps very slightly on the brisk side. Only in the Trio of the Fourth's Scherzo is Ticciati somewhat too leisurely. The conductor uses the 1851 version of the Fourth, the best choice I believe, and once more the interpretation is compelling overall. He effectively conveys both the angst and joy of the first movement, its sense of struggle in the development section, and its ultimate resolution in triumph. Notable also is the second movement, which sounds so irresistibly forlorn in the outer parts, and so charming and light in the middle section. The finale brims with energy and high spirits.

In the First Symphony, the opening movement is paced perfectly, it seems, the main theme exuding vitality and joy, the dynamics well judged throughout. Overall, this is a fine "Spring" Symphony to rank with the best versions. The Second Symphony, probably Schumann's greatest, also gets an excellent reading from Ticciati, exhibiting much the same virtues as in the other performances here. The first movement introduction is exquisitely atmospheric and the busy main theme comes across with such vibrancy and energy. Accents and dynamics are so well placed throughout and phrasing in general is so compelling that it's almost hard to imagine this movement played any other way. I must say that the string articulation in the Scherzo's main theme is quite impressive, and that's no mean feat. The remainder of the symphony is on the same high level.

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra may well be a world-class ensemble – they certainly play on that level in these symphonies. The sound reproduction from Linn is vivid and well balanced. Karajan has an excellent set of the Schumann symphonies on DG dating back to 1972, but fine as it is, I would now prefer this one by Ticciati because the performances are also superb and the sound reproduction state-of-the-art. If you're interested in Schumann's symphonies, worthwhile works all, you can't go wrong with this splendid new set. The Brahms symphonies from these same forces are due shortly and I anxiously await their release.

Copyright © 2018, Robert Cummings