The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

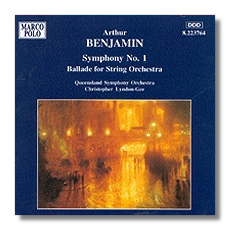

Arthur Benjamin

Orchestral Music

- Symphony #1 (1944-48)

- Ballade for String Orchestra (1947)

Queensland Symphony Orchestra/Christopher Lyndon-Gee

Marco Polo 8.223764 58:25

Summary for the Busy Executive: No tip.

For some reason, we tend to want to hear not only the same composers, but the same pieces over and over. Arthur Benjamin, Australian-born but long resident in England, seems to have fallen victim to his one "hit" - Jamaican Rumba, delightful but hardly representative of his output as a whole. Benjamin has no real settled style. His musical intellect wandered down many paths. Depending on where you looked at his career, you would have thought him influenced by Gershwin, Walton, Sibelius, Bax, Hindemith, and others. He settled in at the Royal College of Music as a professor of piano, where his students included Benjamin Britten and, improbably enough, Anna Russell, who considered herself Benjamin's professional despair (he was, however, one of her many fans, though not of her piano-playing).

During his life, Benjamin enjoyed the interest of world-class musicians, including Heifetz, who recorded his Romantic Fantasy twice. It's easy to see why. From Stanford, Benjamin had learned both facility and craft. This, plus his distinguished "light" music, sunk his posthumous reputation. After all, as good Romantic children, we suspect facility and craft, associating them with superficiality and "mere" craft, antithetical to real inspiration. For many years, Malcolm Arnold's music suffered from basically the same rap. Benjamin doesn't make it easy, however. We tend to judge the worth of composers by something that makes their music unique or quickly identifiable: Stravinsky, Hindemith, Bartók, Vaughan Williams, Shostakovich, Poulenc, Prokofieff, and so on. Benjamin's music hasn't got a distinctive profile. He does what many composers do, but very, very well. This makes his more ambitious work difficult to bring off.

Certainly, the symphony and the Ballade qualify as ambitious. Indeed, they may surprise a listener acquainted only with Jamaican Rumba or Cotillon. I feel at a loss commenting on either one, because the performances - the only ones I've heard - are so feckless. Jack Rollins, super-agent and patron saint of great American comics, once took a young Dick Cavett, at that point a superior comedy writer and an aspirant as a performing comedian, to a club to see a hot young act. After the comic had finished his set, Rollins asked Cavett what he thought. Cavett pronounced the jokes well-written and the performance polished. Rollins replied, "Yeah, but he didn't leave a tip" - meaning that the audience had no idea who the comic was or was supposed to be. Comics like Jack Benny, the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, Burns and Allen, Laurel and Hardy, and Woody Allen (another Rollins client) gave you a world through the gags. Sometimes they don't even have to do a joke. Off-hand, I can't think of even one joke either Laurel or Hardy told. A lot of it comes from a delivery that tells you something precise about character, about relationship, about "neighborhood."

Compared to symphonies roughly contemporary - Vaughan Williams' Sixth, Bax's Seventh, Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem, Stravinsky's Symphony in C Major, Copland's Third, Hindemith's Symphony in E Flat Major, for example - Benjamin's music hardly startles or surprises. But it is felt. The idiom approaches Bax more than it does anyone else. The opening movement should lower like a sky full of storm clouds and thunder. With Lyndon-Gee and the Queensland it's no more than Generally Sad. Lyndon-Gee also seems to have little grasp of the architecture of the piece. One reviewer described this motifically-tight work as "rhapsodic." It wasn't a compliment. It's the same with the Ballade, another thematically complex work which the band seems simply to read through. Furthermore, the strings are alternately raw and weak, disastrous in a piece for strings. One can easily imagine both works played much better. The recording does Benjamin little good, unfortunately. We will have to wait for another.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz