The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

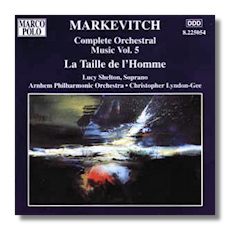

Igor Markevitch

Complete Orchestral Music, Volume 5

- La Taille de l' Homme

Lucy Shelton, soprano

Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra/Christopher Lyndon-Gee

Marco Polo 8.225054 57:01

Summary for the Busy Executive: Half a loaf.

Igor Markevitch had one of the most bizarre and, in my opinion, tragic careers in music. He jumped into the Paris musical scene with works so bold and so original, most praised him as a second Stravinsky, and he was still a teen. The joke ran that he was Prince Igor to Stravinsky's King Igor. He won the praise of both Nadia Boulanger, the Athena of Modern music, and Bartók. Indeed, Bartók cited Markevitch as an influence. However, in 1942, at the age of thirty, after an illness, Markevitch stopped composing altogether. He spent much of World War II fighting with Italian partisans. He emerged postwar as a full-time conductor, admired for his interpretations of the Russians (especially Tchaikovsky) and of the Moderns. Unlike most conductors who composed – Furtwaengler, Szell, Klemperer, Maazel, for example – Markevitch was primarily a composer who conducted, although he did both at the highest level. As much as I admire Szell's conducting, I can't call his compositions (the few I've heard) all that necessary to anyone's listening life, and the same goes for the others I've mentioned. But Markevitch's music, like that of Bernstein and Boulez, strongly claims one's attention. Markevitch declined to conduct his own music (unlike either Boulez or Bernstein), believing that other works deserved a hearing more than his, and thus denied his composing self a venue and a persuasive champion. Marco Polo has come out with a series of recordings conducted by Christopher Lyndon-Gee. It's a series long overdue. I believe they're up to volume seven, although you'd be hard-pressed to find anything beyond volume five in the U.S.

Markevitch once remarked that not only does the composer play with time, time plays with the composer. Previously obscure work suddenly comes to notice, and listeners wonder how it could have been lost. Perhaps Markevitch referred to hopes for his own strikingly original work. One can see the influence of Stravinsky, particularly of the master ballets Apollo and Orpheus, but also more grit, a tendency to work with extremes of tenderness and vigor. Markevitch, like Honegger and Milhaud, has taken some of the "deep structure" of Stravinsky and forged something of his own. Stravinsky himself started out hostile to the younger man's music, but finally came around.

La Taille de l' Homme (roughly, the human dimension) comes from 1939, and thus near the end of Markevitch's composing life. An odd work, it began in the composer's mind as a evening-length chamber cantata, with elements of song, chamber music (including, at one point, plans for a string quartet), and chamber concerto. Markevitch completed the first part and the war intervened. After the war, Markevitch asked his librettist, C. F. Ramuz, who had supplied the story for Stravinsky's L' Histoire du Soldat, for the second part, but the poet had gone into a funk and off the boil (he died in 1947). Consequently, you may sometimes see this work listed as "first part," but don't waste your time looking for the second. It languished unplayed for decades. Markevitch himself went without hearing this work until a few years before his death when somebody enterprising got up a festival of his compositions. The libretto, as far as I'm concerned, huffs and puffs grand sentiments about the human condition with all the insight of a high-school senior. Maybe it's better in French. At any rate, it inspired some white-hot music. The forces are chamber-size, although Lyndon-Gee unfortunately augments the strings in some movements. This puts a kind of down comforter around the music, distancing it from Markevitch's conception. The music itself stresses extreme independence of parts – rhythms, colors, themes, and so on. It's as if musicians in different parts of town jammed telepathically and everything fit together. Markevitch emphasizes instrumental contrast rather than blend so that this independence comes out. Lyndon-Gee hasn't ruined things irrevocably, but he does undermine the composer – particularly regrettable since this is the first recording.

The performance is better than okay, but not spectacular. Lucy Shelton sings with a mouthful of hot mush. With the text in front of you, you will have a tough time identifying the language as French, let alone following along as she sings. If Lyndon-Gee spends more time with the score, he surely will find clearer shapes and longer paragraphs. The sound is pretty good.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz