The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

American Symphonies for Band

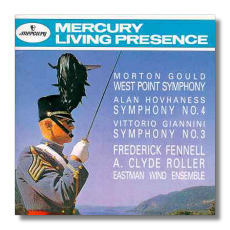

- Morton Gould: West Point Symphony (Symphony for Band) *

- Vitttorio Giannini: Symphony #3

- Alan Hovhaness: Symphony #4

* Eastman Wind Ensemble/Frederick Fennell

Eastman Wind Ensemble/Clyde Roller

Mercury Living Presence 434320-2

Like many others, I got my first taste of symphonic band repertoire from Frederick Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble. His programming ran mainly to Brits and Americans (although I treasure his outstanding LP of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Hindemith). Not only did I get to explore a genre, I also got to know the music of Great Britain and my own country. While my conservatory friends were slaving away at Beethoven and Brahms, poor souls, Lucky Me got to listen to Piston, Barber, Vaughan Williams, Holst, and Hovhaness. There's lots more of this stuff in the Philips vaults, waiting CD transfer.

The current CD brings together selections from two favorite albums: the Hovhaness and Giannini appeared together; the Gould appeared originally with, I believe, Persichetti's Symphony #6 for band.

Gould made a nice living, as they say, without ever really breaking through to the top echelon of composing careers. He even won the Pulitzer. However, his catalogue – full of wonderfwork – doesn't boast a full-fledged hit. To some extent, his lack of broad recognition can probably stems from his permanent feud with Leonard Bernstein, which robbed him of the New York venue and of the most persuasive advocate of American music of his time. Nevertheless, great stuff awaits the intrepid listener. The West Point Symphony to me has only one major problem: the sound of marching feet for a few minutes near the end of the first movement. The risk doesn't come off, because the 1-2-3-4 rhythm fails to spark much interest – fatal for essentially a percussion effect. If you can push that to the background, the band throws off showers of rhythmic and contrapuntal sparks. The work begins with a Hindemithian melody harmonized in a way personal to Gould (influenced by jazz voicings) and with jazz-derived rhythms that simply wouldn't have occurred to Hindemith. The opening theme splits nicely in half. The composer plays around with the head and then with the tail. The work then moves into a tremendous contrapuntal section, where the trebles vary the theme's tail over a basso ostinato derived from the head and seem to half-remember other marches as well – three rhythmically independent contrapuntal strands. It comes across like an army of ghosts. Not for nothing did Gould title the movement "Epitaphs," and yet there's nothing conventionally funereal about it. To me, Gould poetically re-imagines the genre. The ostinato itself amazes me as a feat of composition: it's rhythmically asymmetric, it compresses and inverts the original intervals of the theme, and it all coheres. Add to this a mastery and variety of invented wind colors, and you still end up with a damn good piece, despite them tramp-tramp-trampin' feet. For my money, the second movement surpasses even the first. It's a roller-coaster ride with wild harmonic, full-triad side-slips and snare-drum rhythms in the winds that keep winding a listener up – again, a splendid re-imagining, this time of fife-and-drum music (sometimes even canonic fife-and-drum). Throughout most of the movement, Gould keeps a lid on, mainly dynamically, letting little bursts of energy occasionally break through the texture. This is music coming to eruption, and when it does, it spits notes like the rattling of shot. The work is generous with invention.

Fennell lets his attention wander in the first movement, which loses some of its momentum as a result. The colors of one wind combination, especially in the first part, should melt almost imperceptibly into the next. We tend to get – not stops and starts, exactly – but an effect like someone carrying on in a daze. Still, when Fennell gets to the counterpoint festival of the second half, everything suddenly comes into focus. He commits to the marching feet – much as Chris Farley committed fully to some of the worst sketches of "Saturday Night Live." Gould can't accuse him of pussy-footing here. The second movement is a marvel of precision and high spirits.

The Giannini symphony has its own attractions. When I heard it, I thought, "Very Eastman," by which I meant that group of composers from the Eastman school with a great deal of craft, a sense of beauty, and rather indistinct artistic personalities. The Giannini is by no means shoddy goods, but it sounds like so many other things: a little Hindemith, a bit of Stravinsky, a soupcon of Thirties British modernism. No one says Thou Shalt Be Original, of course, without wasting their breath, and originality isn't everything. Giannini to me succeeds best in the fast movements, where he can generate excitement through quick tempo and distinctive rhythm. The rolling-thunder opening promises more than it delivers, in my opinion, and the lyricism of the slow movement simply fails to interest me. The worst you can say of the wind writing is that it's been done at least once already (Vaughan Williams roughly 30 years before in his Toccata Marziale). Come on, guy, give us some TUNES at least.

A. Clyde Roller gives us great sound and a performance the composer should have rejoiced over. He almost makes you forget how second-hand the music is.

No such problems in the Hovhaness, of course – one of the composer's most inspired and consistently-wonderful works. Hovhaness has always seemed to me a composer of inspiration and tremendous facility. There's apparently no hitch from his mind's ear to his pencil point. What we get, more than with most composers, are first thoughts, often breathtakingly beautiful, but sometimes repetitious and routine – his own routine, certainly, but routine nevertheless. In light of his huge output, however, we forget the tremendous amount of work Hovhaness put in to fashion this idiom. He destroyed a catalogue as large as some composers' life work, and he has continued to expand his expressive and musical resources. His writing for band sounds like none other. I think especially of the solo bass trombone against trombone glissandi or the glitter of vibraphone, glockenspiel, triangle, chimes, and gong – both in the last movement. Striding fugues, noble hymns, and the chatter of stars – what's not to like? Roller and his players give the piece a heartfelt, ecstatic reading. A work of wonders, and a classic performance of the stereo era.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz