The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Brahms Reviews

Dvořák Reviews

Shostakovich Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

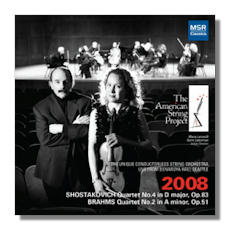

The American String Project

Live in Seattle 2008

- Dmitri Shostakovich:

- String Quartet #4 in D Major, Op. 83

- Johannes Brahms:

- String Quartet #2 in A minor, Op. 51 *

- Antonín Dvořák:

- String Quartet #5 in D minor, Op. 34 - Adagio **

American String Project//Maria Larionoff

* American String Project/Jorja Fleezanis

** American String Project/Stephanie Chase

MSR Classics MS1316 71:52

Summary for the Busy Executive: Transformations.

As I understand it, the seed of the American String Project grew initially in the head of Barry Lieberman, former Associate Principal Bass of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, who envied the great chamber music repertoire available to other string instruments. He began to arrange string quartets for string orchestra, and he and his wife, violinist Maria Larionoff (concertmaster of the Seattle Symphony), got up the idea of asking their string-playing friends around the country to come together for a week and perform the results. This resulted in the American String Project, now in its tenth year. The ensemble has no conductor, but it does use "leaders" – ie, players who sit at the first desk and take responsibility for the interpretation of a piece. To a great extent, they function like committee chairs, fielding suggestions from the group as well as contributing themselves.

I would guess that most listeners entertain a prejudice against artistic committees. We have become used to the idea of the single great interpreter who divines and shapes a masterwork. I can judge only by results. Groups without a conductor vary considerably in quality, just as they do when led by a maestro. In general, the American String Project does very, very well.

Transforming a string quartet into a string-orchestra score takes more than simply transferring the violins, viola, and cello and doubling the cello with the bass. It takes considerable, subtle art, an understanding of both media, an appreciation of their differences, and a composer's insight into the score at hand. Choosing the right work turns out to be extremely important. Not all string quartets do well in expanded form. I've heard other Lieberman arrangements, including one of a Beethoven string quartet that became a kind of an "extra" Beethoven symphony. On the other hand, not all of Lieberman's choices have been so happy, although when he's "on," he's superb.

Other hands (Rudolph Barshai's among them) have expanded some of the Shostakovich string quartets into chamber symphonies, so my hopes for the Shostakovich-Lieberman String Quartet #4 began pretty high, and the realization exceeded them. The quartet, one of the composer's works written in the wake of the official Zhdanov condemnation of himself, Prokofieff, Khachaturian, and others, found its way, along with the Violin Concerto #1, to Shostakovich's desk drawer until political rehabilitation. Given the circumstances, we shouldn't be surprised at its exposure of nerve and stress. With the transcription, we get, in effect, a different work, less intimate than the quartet, but still relatively modest – an Angst-filled serenade. Like Barber's various arrangements of the adagio movement of his string quartet, Lieberman's Shostakovich exists as a satellite of the original, provoking a different response, valid in its own right.

Mixed results in the Brahms, however, where the transcription doesn't really catch fire until the third movement. I've thought about why Lieberman does less well here. I suspect that success depends on the amount of "air" in the string writing. The Brahms String Quartet #2 – at least the two opening movements – to me represent Brahms trying to give the string quartet more bulk than usual. The counterpoint is dense and the instruments pretty close together a good deal of the time. This gives a certain weight or strength to the music. However, when translated to the large string ensemble, with a double bass, the music becomes as unwieldy as a fully-inflated Michelin Man blimp. The ensemble really can't come together as a true chamber group, because they have insufficient space to themselves. At the third movement, however, the ensemble's cosmic gears seem to realign, and they become self-aware, sensitive listeners, shaping the music, rather than being pushed around by it. I must also point out Lieberman's brilliant scoring of the final movement – an especially canny opposition of solos against the mass.

The Dvořák movement, an encore, is just plain lovely. It sounds bone-simple, but its nine minutes must result from the composer's considerable art, since nobody brainlessly sings their head off so beautifully and so to the point for that long. Despite its low opus number, it's actually a work of the composer's maturity. In fact, it's the ninth quartet in the cycle. Dvořák's publisher – for reasons that never made sense to me – played games with such designations, moving early to late and vice versa, and thus insured work for generations of musicologists. Again, the transcription works as well as the original, but to different effect. Here, the strings just hug you, like a nice warm blanket.

The CD records a very fine live performance. Indeed, you forget the audience until you hear its applause. The American String Project's motto, "A virtuoso in every chair," may indulge in a bit of hype, but not too much. You do sense that any one of these players could assume with credit a soloist or leader role. Overall, a disc that will give you many evenings of pleasure.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.