The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Arnold Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

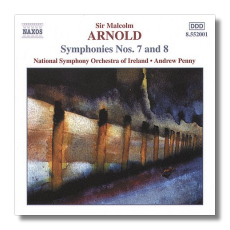

Malcolm Arnold

Late Symphonies

- Symphony #7, Op. 113

- Symphony #8, Op. 124

National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland/Andrew Penny

Naxos 8.552001 63:55

Summary for the Busy Executive: Devastating.

I had intended to review two Malcolm Arnold film scores (The Roots of Heaven and David Copperfield) on Marco Polo, but they seemed to have dropped from commercial circulation. I have about a two-year backlog on my reviews and I've developed ways to reduce it. I don't review things I don't like or that don't interest me, because what's the point? I have made exceptions for things I felt have gotten a buzz they didn't deserve. Another reason – one I feel guilty about – is the CD no longer available from large distributors, like Amazon or ArkivMusic. I've also made exceptions about this, particularly in the case of less well-known composers and performers who run essentially a home operation in CDs. So consider this an alert, something to watch out for. The Marco Polo CD is recommended, particularly for those who enjoy great film scores. It may eventually show up on Naxos.

But of course I haven't run out of Arnold to review.

The composer initially foxed me. I remember one shopping trip to the best record store I've ever been in – Liberty Music in Ann Arbor, Michigan. My favorite clerk, Millie, who also knew an awful lot about hot jazz and le jazz hot – recommended the fifth symphony to me. "I don't know," I said. "I haven't made up my mind about Arnold yet." She replied that was probably a good sign. Anyway, I ended up with the LP. Nevertheless for years, I had accepted the standard palaver about Arnold: essentially a light-hearted (the term one usually encountered was "Falstaffian") composer, a superb technician, and an unfortunate vulgarian, a musical Benny Hill. Some of his music fit the description, but much of it didn't. Works that began lightly seemed to lose their way or to settle for something easy. Incidentally, except for the hail-fellow-well-met quality, I felt much the same about Shostakovich for many years.

That should have given me a clue, but I was too dense to pick it up. In the meantime, I simply couldn't make up my mind about Arnold's music. Certain works – like the concerto for two violins – stunned me with their near-Mozartean beauty. Others, like the third and fifth symphonies, seemed empty bores, knock-off Walton. It took the seventh symphony to turn me around. The score resisted all the standard phrases about Arnold and shredded the canned preconceptions about the composer. It forced me to really listen and led me to re-evaluate his achievement.

And, at second and even third look, it's an impressive one. In fact, Arnold's cycle of nine symphonies strikes me as among the finest of the century. Writers have often compared Arnold's symphonies to Walton's, to their detriment. As knock-off Walton, they're not particularly successful. But why compare them to Walton at all? The surface idioms may resemble one another, but the nature of the two composers are no more alike than, say, Bruckner and Mahler. In fact, Arnold seems one of the few Modern symphonists who actually took in some of the lessons of Mahler. He develops his material through juxtaposition and contrast. The symphonies move through virtuosic counterpoint, made apparent through scoring of virtuosic clarity. There's also an element of grotesquerie, which comes out in parodies of "low" musical elements – calypso, rag, folk music, Salvation Army bands, and so on. While Arnold has certainly written his share of light-hearted pieces, his fundamental vision remains quite dark, apprehended most easily in his last three symphonies.

Arnold dedicated each of the three movements of his Seventh to his three children. I hope to God he hasn't written portraits. This is a symphony of almost unbearable laceration. The mood is usually dark and lowering. When bright sounds come in, they sting, rather than comfort, like looking directly into the sun. The first movement throws short ideas at us like jagged pieces of scrap metal. Eventually, a Waltonian "weeping" theme blossoms, but Arnold develops it in an un-Waltonian way, essentially by throwing the scrap against it. Eventually, the weeping transforms into a bizarre ragtime march, which Arnold rubs in your face. There's a short recap, with hits on a Mahlerian cowbell, recalling the "strokes of fate" of the earlier composer. The movement ends brazenly, with loud splats and smears of notes, but finally inconclusively, a half-tone below the key center. Masterfully, it functions like a leading tone into the second movement. Mostly quiet, that movement nevertheless brings no comfort. It is practically a clinical dissection of sadness. It has an objective quality, almost entirely free (one little section toward the end) of self-dramatization or self-pity, like reading a physician's chart. It sings without hope, because circumstance doesn't warrant hope or transformation. This music comes from the Slough of Despond. Yet it does move, although through a bleak landscape, to be sure. Arnold's main instruments for carrying you through are tuned tom-toms, of all things, beating like the tell-tale heart. Eventually, we hear the cowbells, with even more brutal whacks, and the movement ends inconclusively, this time a half-tone higher than the key center. This generates the tension that leads you to the third movement, which takes massive strides, like some giant destructive machine. The music gets almost imperceptibly softer, until you find yourself almost at the edge of hearing. At this point, Arnold throws in an enigmatic bit, an evocation of Celtic folk bands in full tootle. This, too, fades, and the opening assault returns with, once again, the three wallops on the cowbell. There's no suavely-worked ending, neither to triumph or defeat – three granitic chords and that's it, a giant "f*** you," in effect.

The Eighth Symphony, written five years later, nevertheless continues much of the mood of the Seventh. It begins with the same sort of rock-throwing gestures, but out of nowhere comes a thoroughly trivial Irish marching tune, very reminiscent of Colonel Bogey. This gets smashed to bits, and the movement consists of putting it back together. The drama lies in the unexpected substance Arnold distills from the tune and from the shards of the tune. Things get pretty worked up until the tune returns again in pretty near its original form. This represents a resolution, but only of sorts. Arnold ends with the soft roar of the tam-tam, a disturbing undercurrent to the mindless one-two of the little march. The slow second movement begins sadly, but tenderly, in the strings and solo winds. It elaborates a single theme, unwinding it like thread from a spool. The music grows bleaker and bleaker and proceeds in mostly muted colors, although at one point bright, quiet bells break in. Yet, it doesn't bring joy, but a glittering uneasiness – a Bernard Herrmann moment, if you like. The general gloom overwhelms the bells, however. We seem to head for quiet waters, but a minute before the end, there's a brief, anguished cry from the brass. This serves as the climax of the movement, and you have to wonder about its placement as well as its mayfly-life. Soft strings take over with a simple minor chord and break your heart.

Given all that, the third movement comes as a very rude surprise. It's a rondo on, I believe, two themes – the first, incredibly chipper; the second, far more disturbing. It's also a mini concerto for orchestra, emphasizing sectional virtuosity, including a glorious passage for percussion, with the end gathering up the full orchestra for the final bit of flash. Arnold the orchestrator comes up with one fabulous new texture after another. Yet I find myself wondering why this movement, however brilliant in itself, is in the symphony at all. I have no answer. It's not a transformation, but a stark swing between mania and depression, with mania winning out. I'm more shocked by this movement than by anything in, say, Stockhausen or Berg. It's that ambivalence of juxtaposition again. I can imagine how the Viennese felt at something like the première Mahler's First.

Andrew Penny and his Hibernians fully match the earlier Conifer forces with Vernon Handley and the RPO. There are, of course, differences, but overall impact remains the same – shattering. Penny and his band also have the complete set, if you feel like plunging.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz