The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Berio Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

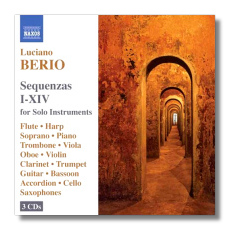

Luciano Berio

Sequenzas I – XIV

- Sequenza I for Flute (1958) - Nora Shulman, flute

- Sequenza II for Harp (1963) - Erica Goodman, harp

- Sequenza III for Female Voice (1966) - Tony Arnold, soprano

- Sequenza IV for Piano (1966) - Boris Berman, piano

- Sequenza V for Trombone (1966) - Alain Trudel, trombone

- Sequenza VI for Viola (1967) - Steven Dann, viola

- Sequenza VII for Oboe (1969) - Matej Sarc, oboe

- Sequenza VIII for Violin (1976) - Jasper Wood, violin

- Sequenza IX for Clarinet (1980) - Joaquín Valdepeñas, clarinet

- Sequenza X for Trumpet and "silent" Piano (1984) - Guy Few, trumpet

- Sequenza XI for Guitar (1988) - Pablo Sáinz Villegas, guitar

- Sequenza XII for Bassoon (1995) - Kenneth Munday, bassoon

- Sequenza XIII for Accordion (1995) - Joseph Petric, accordion

- Sequenza XIV for Cello (2002) - Darrett Adkins, cello

- Sequenza VIIb for Soprano Saxophone (1995) - Wallace Halladay, soprano saxophone

- Sequenza IXb for Alto Saxophone (1981) - Wallace Halladay, alto saxophone

Naxos 8.557661-63 3CDs: 63:02, 60:09, 58:48

Summary for the Busy Executive: Beauty and boredom in fine performances.

For some, Luciano Berio (1925-2003) was long a bête noir of contemporary music. Apparently he scared some listeners so much that they forgot to really listen, preferring to bring instead a grab-bag of adjectives that they could apply to most prominent composers of the period: "cerebral," "soulless," and their Roget equivalents. For me, Berio depended less on "intellectual" manipulations than many, especially his compatriot Luigi Nono. Indeed, his music showed a reliance, sometimes an over-reliance, on intuition and the feelings of the moment. I remember a story once told me by a composition professor (with a masters in math) who had gotten a grant to work at the Princeton computer-music project. This was in the days before synthesizers and PC-sequencers (indeed, PCs), when computers took up large rooms, programs were typed on punch cards or teletype machines, and a composer had to specify all the components of a single note, including wave forms and overtones. The professor worked four months of very full days to produce two minutes worth of music. Berio blew in one day and began to twirl dials and push cables into jacks. According to the prof, Berio got nothing usable, perhaps overtones only bats could hear.

From the early Folk Songs through the Sinfonia and the Serenade to his final works, Berio always struck me as a lyrical composer, concerned about the long musical line, even though his "melodies" were hardly conventional or even, in many cases, hummable. The fourteen Sequenzas, mainly for solo melody instruments, run throughout the last forty years of his career. This is the second recording of the complete series, although it lacks the verses the composer wanted recited before each item (for everything, see Mode 161-163, which also features performances by some of the dedicatees). Because most of these pieces belong to single-line instruments like oboe and flute, we get some very interesting takes on how a musical line functions. The great model is, of course, Bach, who not only crafted ingenious watchworks for violin, cello, and flute but also made danceable, delightful music. The solo genre bristles with traps, which Bach seems never to have had to consider, all the while never falling in, so "natural" is the music. Even great composers founder in solo works. I love Hindemith's music, including his chamber music, but his sonatas for solo strings sound cramped, constricted. Berio's Sequenzas have the ingenuity, although I'd be stretching things to say you can dance to them. Nevertheless, they kept my interest, at any rate. Typically, I grabbed on at the very beginning and held on as the composer took me to surprising places. They cover a wide emotional range and often contain great humor. Predictable, these things are not.

Highlights of the set begin with the first track, in which the solo flute darts, flits, and hovers like a hummingbird. The coolly meditative second Sequenza for harp gets to the soul of the instrument. On the other hand, the Sequenza III, perhaps the best-known of the set, I've never liked. It always struck me as a catalogue of virtuoso vocal technique – not surprising, since the composer wrote it for his ex-wife, Cathy Berberian, who could sing anything (and sometimes did) – rather than something expressive. Number four turns the piano into a chamber ensemble, with its juxtapositions of planes of music – high, medium, and low registers – and a frenetic energy reminiscent of a Charlie Parker solo. The fifth, for trombone, does the same with a melody instrument, making a polyphonic composition from a monophonic one. Like Sequenza III, the trombonist trots out tricks and timbres, new and old, to help the illusion, but here the virtuoso writing works.

The three Sequenzas for strings – numbers VI, VIII, and XIV for viola, violin, and cello, respectively – show Berio's inventiveness, as well as his ability to take from a wide variety of sources. The character and conceits of each one differ. The piece for viola begins with virtuosic agitated chords (Richard Whitehouse's succinct liner notes suggest Paganini), from which the player begins to carve a melody. The music becomes predominantly linear as it progresses. It suffers from its length, however, taking far too long to establish its point. The Sequenza for violin takes off from Bach, specifically the celebrated chaconne from the second partita. Bach inspires Berio to the top of his game. This is probably the finest item in the Sequenzas. The Sequenza for cello, the last of the set, while not up to that level (very few pieces are), nevertheless delights, as the player gets to recreate the music of the Indian subcontinent, especially the sitar and the tabla. I fe! lt as if I sat in at a Ravi Shankar concert.

This willingness to take in diverse musical traditions and styles also shows up in Sequenza XIII for accordion. Subtitled "chanson," the piece takes on the character of a nocturne, a melancholy turn by the Seine at night perhaps. A beautiful, poetic work, it nevertheless explores new sounds and textures from an instrument so often the butt of jokes.

I should mention the items that never have worked for me, chief among them the Sequenzas IX and X, for trumpet and pianoresonance and for guitar. I perceive absolutely no logic to the guitar piece, after years of listening. It remains a mess and no fooling, one of those works where Berio seems to simply be piling on measures. The trumpet piece first of all goes on way too long. The trumpet's expressive and tonal range is comparatively limited and rather stark, besides. It's no accident that works for solo trumpet (like Kent Kennan's classic sonata) tend to brevity. Recognizing this, Berio tries to overcome the instrument's constraints by having somebody silently press down piano keys and the sustaining pedal, so that the trumpet creates a soft halo of chords in addition to its line. It's a lovely effect, but it's not one that in itself sustains interest over the long haul. We get 17 minutes of long haul, making this the longest of the Sequenzas. I give up caring abo! ut 8 minutes in.

On the other hand, while I never cuddled up to the works for oboe and clarinet, I love them in Berio's arrangements for saxophone. What seemed bland becomes playful and smoky.

This recording amounts to a largely-Canadian affair. The engineering is first-rate, the performers spectacular. Standing out are Nora Shulman on flute, Steven Dann on viola, the pianist Boris Berman and violinist Jasper Wood, cellist Darren Adkins, Alain Trudel on trombone, and Wallace Halladay blowing soprano and alto sax. Soprano Tony Arnold knocked me over with a voice of unbelievable flexibility, on a par with Cathy Berberian herself, as she turned herself practically into an electronic tape from the Sixties. Dynamically and color-wise, she switches on a dime. It's almost like watching a circus act.

Hail Naxos for committing to a wide range of music, especially largely unfamiliar, "hard" music, in addition to the more immediately-accessible. You can get the Sequenzas from other labels, but this set yields nothing in performance quality and costs a lot less.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz