The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Foss Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

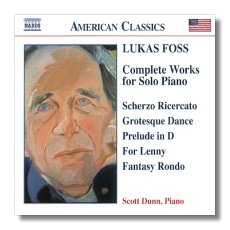

Lukas Foss

Complete Solo Piano Works

- Scherzo Ricercato (1954)

- Passacaglia (1940)

- Grotesque Dance (1938)

- Prelude in D (1951)

- Fantasy Rondo (1944)

- Four Two-Part Inventions (1938)

- For Lenny, Variation on "New York, New York" (1987)

- Solo (1981)

Scott Dunn, piano

Naxos 8.559179 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, 2003 55mins

Summary for the Busy Executive: Renaissance mind.

Lukas Foss has genius, no doubt about it. He composed, probably still in short pants, and produced masterpieces in his teens, a pupil of Scalerio and Thompson at Curtis and of Hindemith at Yale. By the time he reached these men, he hadn't broken twenty and had composed for at least ten years. While he undoubtedly learned from all these men, he very quickly went his own way. He also studied piano at Curtis with Vengerova, who "finished" so many virtuosi. He conducts. He plays the flute. I can't think of a more spectacularly gifted musician other than Mozart.

For me, Foss' music breaks into three periods. The first is neoclassicism, as he follows first Hindemith, then Stravinsky. This is his one of his longest stylistic spans, lasting until about 1960, and it produced almost all of his "hits." Along with Leonard Bernstein, Irving Fine, and Harold Shapero, Foss carried the banner of a vigorous neoclassicism at a time when Stravinsky considered himself played out in that vein. Stravinsky even became a fan: "I find it beautiful, this music of yours." Foss followed this with a radically experimental phase where he explored dodecaphony, aleatorics (so-called "chance music"), group improvisation, among a host of other trends, even mixing a few, all with his own point of view and superb musicality. You may not like works from this period, but you can't say they're unmusical or badly-written. About thirty years ago, he abandoned the hard-core avant-garde for a more eclectic approach, tonally-based and always open to new paths, allied to his earlier neoclassicism. For all his exploration, however, Foss never really started anything. He extended and deepened paths laid out by others. Mozart didn't innovate either.

For a pianist good enough to concertize, Foss hasn't written all that much for piano solo. It all fits on one disc. Despite the claims on this jacket about recording premières, the label Sonatabop produced an identical program at least a year before Naxos. However, Sonatabop is an obscure label at a higher price, and Scott Dunn does quite well indeed. One can safely assume that Naxos has commercially, at least, superseded the pioneer.

The lion's share of this music falls into Foss' neoclassical period. Really early works, like the 4 Two-Part Inventions and the Grotesque Dance, follow Hindemith rather than Stravinsky. Sections of the Grotesque Dance (more lyrical than grotesque, actually) recall the piano writing of Hindemith's second piano sonata of 1936. One must say that the work yields nothing in quality to the Hindemith, and Foss is roughly sixteen years old. If the Inventions don't reach quite that level, this may have something to do with their origin. Foss wrote them on the subway, presumably while traveling to and from a lesson. An air of schoolwork hangs over them, even though the level is advanced study. Like his model Bach, Foss often implies a third voice in the two-part writing.

Two years later, with the Passacaglia, we note that Hindemith is far less prominent. Also, Foss' impish sense of humor comes to the fore. In a TV interview, back when classical composers were still considered important members of society, Foss talked about Mozart's love of reconciling incompatible musical ideas, and Foss' admiration and attraction for this point of view clearly showed. Foss has written a passacaglia, quite serious in its expression, and yet with a joke underneath. Most of it doesn't even sound like a passacaglia, although the bass line carries through, usually disguised as something else. Foss does many things to hide the bass line – break it up among various registers, bury it in nearby contrapuntal lines, and so on. And yet the piece moves inexorably over a nice span.

Foss' love of contradiction comes out in the title of his Fantasy Rondo, one of his largest works for solo piano. "Fantasy," of course, leads us to expect something free-wheeling, while the rondo is one of the most clear-cut of the classical forms. The piece begins, not with the rondo theme (as in almost every other rondo), but with a longish grave introduction based on the rondo theme. The "fantasy" part comes down both to capricious changes of mood and to the fact that the rondo theme doesn't appear the same way twice. Hindemith's influence has almost completely disappeared. Foss, in the manner of most American neo-classicists, follows Stravinsky now. Furthermore, there are jazzy passages in a style we have come to associate with Leonard Bernstein. Foss and Bernstein were good friends. Who thought of this kind of jazz evocation first is hard to say, since both the Fantasy Rondo and On the Town both come from 1944. One can say that Bernstein made greater use of it in works like Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs and the Second Symphony (in which Foss played the piano solo for two of Bernstein's recordings). Foss, however, quickly moved on.

On the other hand, the Prelude in D has no obvious conceptual ax to grind. I look on it as Foss' attempt to compose a perfect melody, perfectly set, perhaps as in the second movement to Ravel's Concerto in G, although the two works don't sound at all alike. Foss' prelude is in simple A-B-A form, as befits a song. It sings exquisitely throughout its three minutes.

With the Scherzo Ricercato, we find ourselves at the height of Foss' Stravinskian period. Again, Foss does more than merely imitate Stravinsky. He writes at Stravinsky's level and gives us something personal besides. The piece combines features of the scherzo – triple time, lightness and dash – and of many types of ricercar – the toccata, the two-voice ricercar, the imitative ricercar, ancestor of the fugue. Apart from all the lineage, it crackles with nervous excitement and playful invention. For all its spirit, however, it strikes me as a major piano composition of the Modern era.

The most recent work comes from the Eighties. Foss composed For Lenny on the occasion of Bernstein's turning seventy. It's an occasional piece, in much the same way the Bernstein's own series of Anniversaries are, and like those earlier works transcend the original occasion. We have here a quiet little habanera on Bernstein's big and brassy anthem to his adopted city, "New York, New York." It also manages to bring to mind the stylized Latin-American dances of Bernstein's Fancy Free and West Side Story – a poetic tribute to a fabulous career.

Solo, on the other hand, is a bigger, more ambitious piece. In it, Foss seems to sum up his own musical preoccupations through the years: neoclassicism, minimalism, serialism, and so on, all in one piece. Solo runs the longest of all the items in the program, and it consists of such minute changes that you need to listen really hard. To me, it's a more grown-up version of Glass's keyboard music. Strictly speaking, Foss doesn't do classic minimalism, but he obviously starts from there. Indeed, the density of new events speeds up toward the end, with a long, mystical idea tossed from hand to hand about three minutes from the finish, to something like a dramatic climax, and ending on an enigma.

Scott Dunn plays really well, especially in Solo, where the task of keeping the musical thought together is especially hard. In the neoclassical stuff, his tone is bright, his lines clear, his touch ranging from weighty to feather-light. This is some sweet playing, and at a bargain price.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz