The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rózsa Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

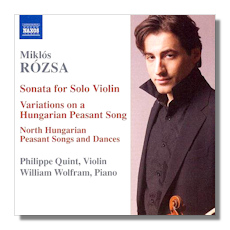

Miklós Rózsa

Music for Violin & Piano

- Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song, Op. 4 (1929)

- Duo for Violin & Piano, Op. 7 (1931)

- North Hungarian Peasant Songs and Dances, Op. 5 (1929)

- Sonata for Violin Solo, Op. 40 (1986)

Philippe Quint, violin

William Wolfram, piano

Naxos 8.570190 60:32

Summary for the Busy Executive: Play, zigeuner, play!

This CD brings together all of Rózsa's chamber music for violin. The violin was in fact one of Rózsa's instruments, although – unlike, say, Grażyna Bacewicz – he never pursued a performing career. However, beyond Rózsa's usual meticulous craft, his hands-on acquaintance with the violin at least assures you of an idiomatic part. The works here come from early and late in Rózsa's career, with the middle taken up mainly by orchestral works and film scores. Rózsa began and ended with chamber music – early, out of a native caution, a "walk-before-run" mentality; late, because of a degenerative illness that made creating full orchestral scores physically too demanding.

The earliest two works, Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song and North Hungarian Songs and Dances (sometimes billed as the Little Suite), use Hungarian folk tunes – as the liner notes point out, two of the three works in Rózsa's entire output that do. Like Vaughan Williams, Rózsa had absorbed the folk music of his country into his musical DNA. Essentially, he "wrote folk music," although this description fails to do justice to both him and Vaughan Williams. I began to think of the similarities and differences between Rózsa and Bartók (a hero of Rózsa's, by the way) in their approach to folk music. Both avoid the syrupy sentimentality of something like de Sarasate's Zigeunerweisen because they regard Hungarian folk tunes as good tunes, rather than as picturesque evocations of the exotic. Bartók, however, went deeper into folk music than Rózsa did. Among other things, it represented the discovery of his musical salvation, a key to his own artistic voice. Through folk music and the example of Stravinsky, Bartók consciously forged his brand of Modernism. Folk music was the gateway to more complex harmonies and newer, freer forms. On the other hand, Rózsa was no ethnomusicologist. Hungarian folk music was something he had heard since he was a boy. It was almost always part of him. In that sense, Rózsa didn't discover himself in folk music. It was something he didn't have to think about. When he caught on to Modernism, the folk basis was inevitably there, and he was always more architecturally conservative than Bartók. Indeed, Rózsa's forms are straightforwardly simple here, but his treatment (he always had an amazingly precise ear) sets these tunes off like jewels. Rózsa thought enough of each to orchestrate them both.

The Duo from two years later shows more ambition. I consider it the best of the early works for violin. It's really a violin sonata, although I have no idea why Rózsa didn't call it that. It encompasses four movements, arranged in the "usual" Hungarian format of slow, fast, slow, fast. The first movement, "Tranquillo," opens with a meditative introduction which features the violin in double stops (playing two notes simultaneously), with just a hint of counterpoint. A bold, rhythmically vigorous theme sets out, followed by a more laid-back, gracious one. The movement very quickly settles into sonata form as these two themes develop. Structurally, Rózsa provides a nice wrinkle. After a recapitulation, the introductory music returns. However, the movement ends not there, but with a unison restatement by violin and piano of the rhythmic theme. Incidentally, I hear a touch of Ernest Bloch, but it probably comes down to a mutual folk source found by both composers. "Allegretto capriccioso" presents a scherzo and trio. The scherzo proper alternates between a stamping 3/4 and a mercurial 6/8, while the trio is more declamatory, in duple time. The gorgeous third movement, "Largo doloroso," may trick you into believing that Rózsa just sings his head off, until you realize that the violin and the piano, independent of each other, sing two different songs.

The finale, "Allegro vivo e giusto," is a sonata-rondo – that is, a rondo touched by aspects of sonata form, which kind of ups the compositional ante. The usual rondo takes a main theme and intersperses its reappearances with what are known as "episodes." The episodes differ from one another. So the form of a typical rondo might be A-B-A-C-A-D-A etc. In Rózsa's sonata-rondo, there are only two themes, both of which the composer subjects to development. A sonata-rondo with two themes would look something like this: A-B-A'-B'-A''-B''-A''' etc., with perhaps the final A section a recap of the first instance, rather than yet another development. Most importantly, however, Rózsa provides yet another exciting race to the finish. The two themes function in a dramatic way. They bump against one another, like roller derby skaters, and we can't wait to see which one will win through. It's by no means a forgone conclusion, especially since Rózsa gives huge amounts of time to the B theme.

Illness caught up with Rózsa in his old age. He no longer had the stamina to compose for large forces. His late work consists of chamber pieces for one instrument: sonatas for solo flute, violin, clarinet, guitar, ondes martenot, and oboe, and an Introduction and Allegro for viola. In a catalogue full of gems, the Sonata for Violin Solo (1985) ranks as one of his finest compositions. Lest anyone think that writing for a solo melody instrument constitutes easy work, think of how many successful pieces there are in the genre, other than Bach's. Having tried and failed to do this myself, I know exactly how hard it is. I ran into two main problems. First, if you're not careful, the music tends to merge into a blah wad, tonally speaking. The violin gives you some scope with its array of bowing techniques, its ability to double- and triple-stop, its wide range of pitch from essentially low alto to soprano and beyond, and its variety of tone, depending on where you bow the instrument. This assumes you really know the instrument. Second, the lack of harmonies puts a composer's melodic skill to an extreme test. Even a great composer can easily degenerate into what sounds like incoherent noodling around. I've heard composers I admire (even love) succumb to this, although I won't name them, just in case somebody wants to call me Philistine.

The sonata breaks into three substantial movements: a sonata "Allegro moderato," "Canzone con variazioni" (another variations set, one of Rózsa's favorite forms), and "Finale: Vivace." This work astonishes me in its running against expectations. It's primarily contrapuntal, rather than chordal or melodic. Indeed, Rózsa uses the various tessiturae and colors of the violin very much like opposing sections of the orchestra. I like the second movement the best, although I don't mean to slight the other two. The coherence throughout also impresses. It comes across as one long song. It doesn't sing with all the lush lyricism Rózsa is capable of, but it's not that kind of piece. It's closer to Bartók and especially to Kodály's Sonata for solo cello. It wouldn't surprise me to learn that the latter work lurked in the back of Rózsa's mind as he wrote.

The performances are just as marvelous as the music – wonderful. Philippe Quint (a native Russian, despite the name) has a piercingly beautiful tone, dead-on intonation, and uncannily accurate fingers. Added to all that, he fairly drips with great musicianship. He doesn't inflate anything. He doesn't condescend to anything. He's not afraid to sacrifice beauty of tone when the music calls for it. Pianist William Wolfram is just as good. Given a star violinist of this quality, many accompanists would simply lay back and let the star do his thing. Wolfram doesn't lie down, and furthermore Quint won't let him. I've heard from Wolfram more of Rózsa's elegant counterpoint in the piano than from any other performance I've encountered. This is a true chamber collaboration. You get the impression that, as in jazz, both players riff off one another spontaneously – more likely a tribute to their capacity for hard work as well as to their musicianship. I keep saying this, but this Naxos disc will probably wind up among my favorites of the year.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.