The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bloch Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

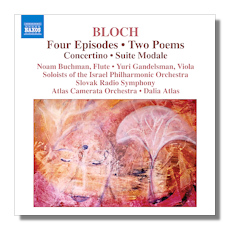

Ernest Bloc

Orchestral Music

- 4 Episodes *

- 2 Poems **

- Concertino

- Suite modale

Noam Buchman, flute

Yuri Gandelsman, viola

Atlas Camerata Orchestra/Dalia Atlas

* Soloists of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

** Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra/Dalia Atlas

Naxos 8.570259 52:29

Summary for the Busy Executive: Mighty minis.

I used to complain that Ernest Bloch's music hadn't gotten the attention it deserved. In the concert hall and the academic journal, it remains true. Thank the gods for CDs. Not only can you get umpty-tumpty versions of Schelomo, with just about any star cellist you care to name, but you can choose from among seven performances of the Piano Quintet #2. For a long time, there was no recording of this piece. Recording labels are now delving into Bloch's catalog, hauling back both major and minor works.

The program here, with one exception, doesn't represent top-flight Bloch, but the contents of Bloch's second drawer is miles beyond that of most composers' first. Dalia Atlas has given us a fine picture of Bloch early, middle, and late. All the works here typify their period.

The earliest pieces, the 2 Poems (perhaps better known as Hiver – Printemps), come from 1905, after Bloch had soaked up Impressionism in Paris. Yet even here, Bloch sounds like no other impressionist, even though he uses some of the same devices. Impressionism as the French practiced it was primarily a matter of the beauty of the surface. Bloch (who had earlier succumbed to the influences of Mahler and Richard Strauss) aims at portraying psychological states. One doesn't get Vivaldi's sting of the snowflakes or Debussy's sea wind, but a meditation on gloom – in Robert Frost's phrase, inner rather than outer weather.

The 4 Episodes for chamber ensemble appeared in 1926 and although not as ambitious as the two violin sonatas (1920, 1924) or the first piano quintet (1923), they all share an idiom which one might describe as "barbaric." Just in case you wondered, this is not one of Bloch's "Jewish" works. Instead, Bloch apparently gets his inspiration from the Far East – China and Bali – which bears some of the same relation to his art as Paris does for Wallace Stevens's poetry. Compared to any of the other pieces, not to mention Schelomo, the 4 Episodes ("Humoresque macabre," "Obsession," "Calm," and "Chinese") come off as a kind of busman's holiday, similar in scale to the Concerto Grosso #1 (1925).

The "Humoresque macabre" depicts a state of mind that attracted Bloch throughout his life – the grotesque and the fantastic, the opposite of what we normally think of his music. It apparently amused him, and he would pronounce the very word "grotesque" with relish and a grin. It opens with a mordant theme in the bass, and this becomes important in later episodes. Bloch liked to introduce cyclic principles, especially in his larger works. "Obsession," like Holst's "In the Streets of Ouled Nails" from Beni Mora, takes a riff (in 7+4, I think) and worries it like a dog gnawing a bone. This also belongs to Bloch's grotesquerie. Bloch varies the orchestration and even builds in a dynamic structure by methodically adding and subtracting instruments. "Calm" provides a pastoral respite. It opens serenely, with a slowly-moving chordal ostinato over which solo winds sing. In mood, it resembles the pastoral movements in the String Quartet #1 and the first Concerto Grosso. The finale, "Chinese," evokes the Chinese theater, which Bloch, long resident in San Francisco, greatly admired. From the testimony of the music, he seems to have been drawn not only to the bright colors and the dancing, but to its exotic and macabre elements as well, especially since the opening theme of the "Humoresque" takes over a good deal of the movement.

The Concertino for flute and viola comes from 1948. Bloch had sunk into a depression and a creative stop during the war years, as news of European Jewry began to reach the outside world. The Third Reich's defeat freed Bloch up again, but his music changed. It became more austere, more polyphonically contrapuntal, and he focused on concentrated forms – chamber music and Konzertstücke, for example. Even his epic mode, though it still packed a punch, became terser. The Concertino is the shortest piece in the program, and one could argue for it as the best. The interplay between soloists and between soloists and orchestra dazzles. Furthermore, Bloch's invention fires on all cylinders, one penetrating idea shooting out after another. My only complaint – if you could call it that – is that it doesn't go on longer. Other than that, a gem, both brilliant and hard. The first movement updates the Baroque, without resorting to the obvious tropes – partaking of the energy of Bach and Vivaldi. The second provides a surprising Romantic take on the slow instrumental arias of Bach, although the melodies and harmonies belong to Bloch. The Concertino with a "devil of a fugato," to paraphrase Elgar.

Bloch wrote the Suite modale in 1956 in admiration of American flutist Elaine Schaffer, who died way too young. The composition, like the Suite hébraïque of 1951, afforded Bloch the opportunity of re-visiting his early "orientalism." Again, Bloch reins in his epic excesses and deliberately restricts his scale. This discipline results in a work of great charm, and one which several flute virtuosi have taken up in the past twenty years – not in the concert hall, of course, but on disc. The first movement moves languidly: "Stay me with flagons. Comfort me with apples, for I am sick of love." The second, in the same tempo, assumes a less sensuous tone. It reminds me of an old man looking over his past life with both affection and regret. The third movement dances a lively gigue, interrupted by a contemplative middle, reminiscent of the previous movement. The finale depicts two moods: slow, bittersweet meditation and a fast, joyous song. These two ideas fade in and out of prominence, with the slow music from the second movement (cyclic principles again) closing out the Suite.

Dalia Atlas has amassed quite a respectable Bloch discography. Some of her recordings I've liked better than others, but this is a fine one. She manages to get three different orchestras to project a consistent vision of the composer and conveys her great enthusiasm for the music besides. The soloists, Buchman and Gandelsman, play superbly. Bargain-label Naxos has issued this release. If you don't know much of Bloch, you will probably find this a good place to start or even to continue your explorations. Now we need a complete recording of his opera, Macbeth in the original French, to my mind as powerful a work as Boris Godunov. Are you listening, Naxos?

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz