The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Brian Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

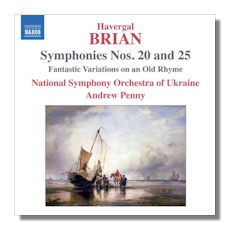

Havergal Brian

Orchestral Music

- Fantastic Variations on an Old Rhyme

- Symphony #20 in C Sharp minor (1962)

- Symphony #25 in A minor (1966)

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Andrew Penny

Naxos 8.572541 62:44

Previously available on Marco Polo 8.223731:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

Summary for the Busy Executive: "There is no off position on the genius switch" – David Letterman.

British composer Havergal Brian had an odd career, one in which he seemed never to catch a break. A younger contemporary of Vaughan Williams, he came to notice roughly in the Teens of the last century and made a splash with his first symphony, the "Gothic," a gargantuan work that dwarfed the already-huge essays of Bruckner, Strauss, and Mahler, both in length and in the forces required. A complete setting of the Te Deum was only one of its movements. However, people came to view the "Gothic" as typical of Brian, and thus the work became a millstone around the composer's neck, especially since the Twenties ushered in a taste for concision. Impresarios so quailed at the expense of putting on Brian's work, that almost half a century passed before the second performance of the "Gothic," mounted by the BBC. Ironically, Brian never wrote another orchestral work as long, and most of his late work is only slightly less condensed than Webern's.

Brian came from working-class poverty and remained poor almost his entire 96 years. Not only did he miraculously learn to compose, he continued to compose throughout his neglect. Remarkably, he completed 27 of his 32 symphonies and 4 of his 6 operas/dramatic works after the age of 72. Neglect hounded him from the Thirties on (at one point, he renounced composition altogether; fortunately, only temporarily) until composer and BBC producer Robert Simpson took up his cause in the early Fifties, by which time Brian had reached old age.

This CD gives us an early work and two late symphonies. The Fantastic Variations on an Old Rhyme comes from a 1908 Fantastic Symphony, which Brian quickly tore apart into two new works (the other being the Festal Dance). The old rhyme in question is "Three Blind Mice." Indeed, since Festal Dance also uses the rhyme, I assume that Brian based all of his movements (although two are lost) on that nursery song. The two surviving movements delight, which leads me to wonder why Brian gave up on the symphony. The Fantastic Variations reveal an eccentric but genuine sense of humor polished to fine finish by brilliant composing technique. The score reminds me of Dohnányi's 1914 Variations on a Nursery Tune. At one point for an early performance, Brian had provided a programme for the piece, a bare-bones plot involving the three blind mice, the farmer's wife, and the policeman who woos her. Despite the title, the work isn't your normal set of more or less discrete variations, but a blend between that and a symphonic movement. Brian also indulges in a bit of satire. The three vision-impaired mice seem based on Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, and Jean Sibelius, with both abstruse and "gettable" jokes. The abstruse jokes tend to point to certain structural habits of these composers, while the obvious ones aim at famous bits of orchestration, melodic habits, and outright themes. One hears the drums of Siegfried's funeral march, the "Wagner appoggiatura" in the love music, and little bits of Don Juan, Also sprach Zarathustra, and (most startlingly) Finlandia. However, none of the jokes has a mean streak. It's all witty, genial fun – Sullivan, if you will, but at an advanced level.

The three-movement Symphony #20, written half a century later in the early Sixties, shows a composer broadening and deepening the basic language with which he began. The score owes much to Mahler, especially in how each of its movements develops. Although the Mahler revival among the general public had just gotten started (the first Mahler box of integrated symphonies under Bernstein appeared roughly six years after Brian's symphony), Brian in fact had been absorbing Mahler since early in the century. It amazes me how much music Brian had heard and knew well, considering his income. In fact, he became a music critic – and an excellent one – largely so that he would get free tickets to musical events, as well as the occasional score. Then as now, London had more concerts and recitals than a spider has babies. Incidentally, Toccata Press has issued his essays in two volumes, available at both Amazon and Powell's web sites. The symphony in its macro details adheres more or less to classical lines: a sonata-like opening movement, a slow second movement, a rondo finale. However, the details are a little tricky. Naxos breaks up each movement into subtracks, and the late Malcolm MacDonald provides an excellent analysis tied to those numbers, which gives me the luxury of concentrating on overall form and mood.

Brian's adaptations of classical forms often strike the purist as a bit skewed. All the elements are present, but the proportions seem a little odd. The opening sonata-like movement, for example, concentrates on the first subject group, almost ignoring the second. To the listener, this movement comes across as a quick march interrupted by two lyrical episodes. The second movement takes on what should be an A-B-A song form, except that it winds up A-A-A – a tripartite structure with three spans based on the same idea. You could argue that the movement consists of an exposition with two variations. In the last span, the relation to the generating idea becomes increasingly obscure, and we hear something like Allan Pettersson's continuous variation technique. The main idea comes back, grandly, only in the last few measures. The last movement relates to rondo form. Brian, as usual, gives it a twist in that almost every episode relates back to the main theme.

The Symphony #25 comes four or five years later. Brian often conceived of his symphonies in sets. Symphony #20 inaugurates one set, and #25, another. However, the sets resemble each other, in that the symphonies alternate between the classically-based and the more free-form. Symphony #25 has three movements, with the first relating to sonata form, the second to song form, and the third to rondo, just like #20. However, Brian this time out gives us even darker work. I'd describe the symphony's atmosphere as "unsettled." The first movement, a march, strides with increasing barbarity. Brief pockets of lyricism bloom and die. The brutality never entirely leaves and finally wins out.

The slow movement reveals a lot about Brian's composing cast of mind. It features two beautiful major themes, from which most writers would have tried to build something of serene beauty. Although just about every section of this movement abounds in such a quality, the piece overall never settles into (nor does it aim for) tranquility. The disturbances Brian injects into the music's course make too large an impression. This part of the symphony made me think of plants trying to fight off a hard winter.

Brian blows away the gloom with a delightfully loopy rondo. Formally, it lies very close to classical practice, even with the wrinkle that the composer varies the main theme with each appearance. Mozart and Beethoven did that, too. On the other hand, given the dismal monuments of the previous two movements, does this rondo belong with its sibs? I love the movement too much to object.

Brian's symphonies are hard for a conductor to get his mind around and an orchestra to get under its fingers. Nobody's yet issued a recording with A-list forces, and furthermore Brian's works still come under the heading of rarae aves. Although recorded performances have improved tremendously since I began to collect this composer over forty years ago, the tradition of performance is far less robust than Mahler's. Andrew Penny and his Ukrainians do a heroic job with every item, but I'd bet that even Penny would love to hear Dohnányi and the Cleveland Orchestra or Barenboim and the Chicago tackle a Brian symphony – not that such performance have a chance in hell of coming to pass, given present circumstances. Nevertheless, the present performers deserve three – even four – cheers.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz