The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- W.F. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

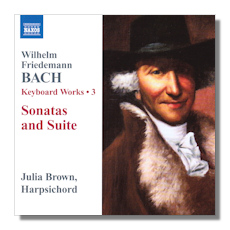

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Keyboard Works 3

- Sonata in E Flat Major, F.5 (BR A 7)

- Sonata in B Flat Major, F.9 (BR A 16)

- Suite in G minor, F.24 (BR A 39)

- Sonata in C Major, F.2 (BR A 3)

- Sonata in D Major, F.4 (BR A 5)

Julia Brown, harpsichord

Naxos 8.572814

For many lovers of J.S. Bach, it's his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, (1710-1784) and not C.P.E. who has the greater invention, subtlety and wholehearted understanding of letting, for example, the pause and rallentando in music make its impact. The sonatas and suite in this, the third in a series from Naxos of the keyboard works (Volumes 1 and 2 are from 2007 and 2008 with Robert Hill and Julia Brown on 8.557966 and 8.570530 respectively) demonstrate well the stateliness, the considered and the balanced, which the deep breath of the gallant style somehow needed to take after the hothouse of Sebastian's Baroque intensity.

Not that this music is in any way slight or inconsequential. Listen to the tonalities of the second (grazioso) movement of the B Flat Major sonata [tr.5], for instance. Brown reveals a large world in its gentle and almost inquisitive cadences… reflective, speculative and calm. But all to a purpose. Brown's playing never wanders as it explores the ornaments which seem to surround it. Nor does she, on the other hand, overplay the necessary emphases which take us from point to point in the movement which follows – actually marked allegro di molto, but which doesn't really pick up speed until half way through. Never does her deft approach to this varied music lack sparkle or momentum.

At times it's almost as though Bach is reminding us of a melodic journey with which we ought to be familiar, rather than laying one out for us with a controlled fervor that jogs mid way between Scarlatti and Haydn. Each of the latter infused their keyboard music with more textural and harmonic "re-enforcement" than Friedemann ever does. In Brown's exposition, it's the rigor (though not once the uniformity) of rhythmic structure that drives the music forward: the opening allemande [tr.7] of the G minor Suite is a good example. In Brown's hands such control and vigor have the effect of heightening our anticipation in ways that Mozart eventually did.

W.F. Bach was a superb improvisor and retained elements of his father's love of chromaticism and the unconventional; more – the unexpected. This is evident both in the composer's conception and Brown's execution of these keyboard works. There is a liberty and sense of fun and engagement that make the music come alive. It's tempting to think, perhaps, that the modern north American harpsichord (by Richard Kingston) is responsible for this flexibility and for projecting Brown's facility with nuance and subtleties of color, particularly in chordal passages. It's certainly a mellow and very pleasing instrument and sound.

No instrument other than "clavier" or "cembalo" – effectively nothing more precise than "keyboard" – was specified by Friedemann; we cannot tell which he preferred. The inference is that it matters little and is a decision to be made by the player. One aspect of this almost hour and a quarter long recital is the variety as well as liveliness which Brown brings to the music – again, thanks to the sonorousness, lighter timbres and flexibility of the harpsichord which she plays. There's nothing ponderous, labored or stodgy. Nor for an instant flippant, flitting or superficial. Her lightness of touch suggests versatility, and the need to let the music go where it will, and not be led. Again, the phrasing of a movement like the opening allegro [tr.12] of the C Major sonata derives its structural logic from something that's both accessible and fresh. Again, though with very different coloring, as do some of Scarlatti's works. Brown is fully at ease with the relationship that Friedemann builds between his own individual sunny and yet thoughtful style and the intensity of his father's idiom, which he overtly honors in such works as the Suite in G minor.

The acoustic, that of a church in Eugene Oregon, is neutral; yet one which focuses attention on the playing, not the atmosphere. The booklet (the notes are by Brown) is brief but informative. If you got the other two issues in this series from Naxos (albeit five years or so ago), then there is no reason why you shouldn't continue this collection. If you want an introduction to delightful, thought-provoking keyboard of great eloquence and elegance, then this is a good place to start.

Copyright © 2012, Mark Sealey.