The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Brahms Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Romantic Piano Trios

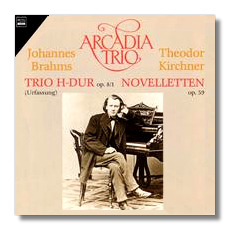

- Johannes Brahms: Piano Trio #1 in B Major, Op. 8 (original version)

- Theodor Kirchner: Novelletten, Op. 59

Arcadia Trio

Preciosa Aulos PREAUL66015

The juxtaposition of the names Brahms and Kirchner initially attracted me to this CD. However, I mistakenly thought the Kirchner was American modern Leon, not Brahms contemporary Theodor. I wanted to see how the players could handle the disparate styles. The truth disappointed me only slightly.

That said, this disc recommends itself in many ways. At the least, it gives us, I believe, the only current recording (one of the rare ones, at any rate) of Brahms' original composition of 1854, rather than the extensive revision of 1890. This is the first time I've heard the original. As far as I'm concerned, either version is a masterpiece, but a different kind of masterpiece. Brahms wrote a lot of notes in between, and his desires for his own music changed greatly. The early Brahms is much wilder, less concerned with architectural proportion and more with getting the listener's jaw to drop at the audacity of the ideas. Actually, this mode pops up occasionally throughout Brahms' career, usually in short piano pieces. Compare the first piano concerto, full of lightning bolts and posies, begun around the same time as the completion of this trio, with the gravely wise second concerto, completed in 1881. The first aims for grand expression, the second for grand scope. We can say pretty much the same of the two versions of this trio.

If we compare the two versions of the first movement, we notice immediately that the revision moves overall with greater power and assurance. The original has too many good ideas (as well as ideas that go absolutely nowhere), and it seems to stop and start as we wait for Brahms come up with his next surprise. The older Brahms is far cannier about transitions from one idea to the next and about realizing the architectural implications of rhythm. A subsidiary corkscrew idea of triplets not only makes for exciting counterpoint in the revision, but it propels the music as well. We lose, however, a gorgeous second-subject group (replaced by something less song-like, but with greater structural "reach") and a truly weird unison idea, first heard in the solo piano. The passage bears the brunt of the development, climbing near the movement's end to a fugal treatment. It's spectacular stuff, but Brahms has no idea how to get to it and settles for another stop-and-start. It doesn't surprise me that he dumped this theme (and almost every passage that followed) in a major rewrite. It's almost as if he went back to his theme books and started again. It seems presumptuous to want to decide which version is "better." They both have their strengths, and the revision has no weakness. On the other hand, it neither soars as high or sinks as low.

Brahms left the second-movement scherzo pretty much alone, but for the end. The original is one of those jaw-dropping moments, where the theme seems to disintegrate into plucks from the strings. The revision also stuns you with its wild and wonderful piano riffs. Again, I see no reason to prefer one to the other, but I don't really understand what moved Brahms to revise his ending in the first place.

The slow third movement tells another story. Brahms, contradictorily enough, once remarked that a work is rarely improved by revision, and, in my opinion, he should have left this one alone. At issue is an allegro that seems to fly in from left field toward the end, before the music settles down with the original theme. Brahms seems to have cut it for the sake of consistency: it's a slow movement; it should crawl throughout. I find the sudden burst of speed a brilliant interruption.

The last movement shows the same extensive overhaul as the first, in the name of concision and more effective movement. We see the same stopping and starting throughout, occasionally expressive, but usually covering up poor transition, and the overstock of thematic material, much of which sounds once and disappears. There's a wonderful moment in the original of this kind, in which we get a manically imitative "Three Blind Mice" in minor mode. One awaits its return or development in vain. The major loss, however, is a beautifully lyric second thematic group. Brahms replaces this by developing the lyrical implications of his first theme and with an energetic idea that reminded me of the Yale "boolah-boolah" cheer. I loved that second theme and miss it, now that I know it's gone.

I raved about the Arcadia Trio's Beethoven (Bella Musica BM 31.2172) and will do the same for their Brahms. From the opening bars, these people play from Brahms' heart. They sail over the difficult issue of balance in piano trios in general (piano overwhelms strings) as if it didn't exist. Each movement is beautifully shaped, with continually changing balance and a profound use of dynamics to elucidate structure. Furthermore, the emotional level of the playing is - appropriately for Brahms - mature. I compared this reading closely with the Ashkenazy-Perlman-Harrell of the revision on EMI 7 54726 2. Aside from my finding Harrell's tone too light for this repertoire, the reading seems "guyed," almost hysteric - in fact, far more appropriate to the original edition than to the revision. Ashkenazy in particular tends to play down line in favor of punch, and the strings follow his lead. The interpretation seems claustrophobic - no room to breathe or expand. It's undeniably exciting, but it strikes me as further from Brahms. Arcadia has far more convincing Brahmsian chops. Above all, this is a performance of equals. Everyone knows when to defer and when to take the lead. If Ashkenazy drives his partners, Arcadia pianist Rainer Gepp becomes part of the conversation.

By the way, Brahms' trio premièred in New York. I remember reading a diary account from a member of that first audience. Brahms had the reputation of an "advanced" musician among those New Yorkers, and the young man was a bit disappointed that the work was not "severe" enough. In the 19th-century tradition of strenuous earnestness, he wanted to be tested. Whatever happened to those audiences?

I suppose Theodor Kirchner is best known as Brahms' friend and the arranger of the two string sextets into piano trios. On the basis of the Novellettes (the only original work of his I've heard), he is either a mighty miniaturist or a composer of symphonies temporarily finding himself in small forms. Checking the Schwann catalogue, I see nothing other than miniatures, so I suspect the former. The idiom is Schumann and Brahms. There are some first-rate ideas here. I miss only that long Brahmsian architectural span and powerful development. Nevertheless, the Arcadia makes a very persuasive case for these.

The sound is a bit close and a bit bass-y, but that doesn't really bother me in this repertoire. Brahms can take it.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz