The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Rachmaninoff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

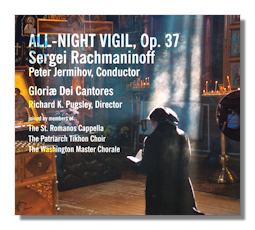

Sergei Rachmaninoff

All-Night Vigil, Op. 37

Dmitry Ivanchenko, tenor

Mariya Berezovska, alto

Peter Jermihov

Gloriæ Dei Cantores/Richard K. Pugsley

The St. Romanos Cappella

Washington Master Chorale

The Patriarch Tikhon Choir

Paraclete SACD GDCD063 Hybrid Multichannel 66:34

Sergei Rachmaninoff's All-Night Vigil, Opus 37 (also known, less accurately, as the "Vespers") was written in 1914, 1915 and first performed in 1915. It is recognized as one of the composer's finest works – as well as being one of his favorites – its fifth movement, the "Nunc Dimittis", was performed at Rachmaninoff's funeral at his request. It's a work that exudes reverence. And a very Russian reverence where exultation (albeit subdued) seems to come from the very soul of the music, which is for choral voices only, rather than any external reference. The text is taken from the Russian Orthodox All-night vigil ceremony. That sense of believing assumed a special importance for Rachmaninoff at a time when the religion which had been a central part of Russian life for centuries was under effective attack.

Here is a new CD from Gloriæ Dei Cantores conducted by Peter Jermihov, who is widely acknowledged as an expert in Russian and Orthodox Liturgical music. The choir is joined by the St. Romanos Cappella, The Patriarch Tikhon Choir and The Washington Master Chorale. Solo parts are taken by Dmitry Ivanchenko and Mariya Berezovska, from the National Opera of Ukraine in Kiev, and by Vadim Gan, Protodeacon under the First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, who sings the clergy exclamations.

This is a very impressive account indeed. Among the first qualities which will strike the listener is the gently persuasive unity of approach: the singers' voices avoid blandness or any feeling that their togetherness is monolithic. They achieve a sense of singular musical direction which is built on technical excellence, not mere will power. The unison in the choral passages suggests a purpose which impresses even the listener who may have little or no insight into the particularities of the Russian orthodox rites.

At the same time, effect for effect's sake is avoided because of the clarity of the singers' articulation of the texts, the variation in dynamic, and an obvious delight in the variety of textures which they achieve (from those corresponding to tiny pinpoints of monochrome candlelight to a flood of color). This command by the choirs consequently builds a consistency which ranges from the mighty to the delicate. Such a range can be heard, for instance in the work's longest movement, the "My Soul Magnifies the Lord" [tr.11]. The singers produce not the waves of a crashing sea, but the undulations of majestic hills.

Another quality is a restrained yet necessary drama. The 80 or so singers aim not for opera, nor oratorio. But for a more ethereal, yet almost visual, again colorful, projection of excitement and thrill. But excitement and thrill derived from belief and veneration. Listen to the crescendo mid way through the "Lesser Doxology" [tr.7], for example: there is more control than abandon; yet there is more true (inner) joy than gesture.

It's a tender joy, too – at times almost rapture. But it's an expression of such emotions by humans, albeit celebrants and a dedicated choir; not musicians seeking to imply they are some sort of force. One way – evident from the very first number, a call to worship – in which these performers make the music so approachable is the subtly varying dynamic from pianissimo to fortissimo.

What's more, both singers and choir(s) achieve a level of excitement and invitation by accomplishing these changes in dynamic more quickly than you might expect – in that first number [tr.1], for example; and at others slowly and in a manner which (as a phrase subsides) draws attention to its place in the phrase; hence its importance. Once you become aware of this added color and depth, you realize just how thoughtful has been Jermihov's conception of the Vigil's overall structure – and hence of Rachmaninoff's purposes in approaching the piece in the first place.

Amongst those purposes were surely regret that Old Russia was changing for good; that certain aspects of choral liturgical music would (inevitably) change along with the broader upheaval of the earlier twentieth century; yet that Rachmaninoff could successfully produce a major work in the genre. It is this faithfulness to the composer's adherence to and love of this genre that is perhaps the most satisfying aspect of this performance. Rachmaninoff's purpose was as much a religious one – if not more so – as a wish to produce a concert piece. Again Jermihov and his forces have succeeded admirably. The wistfulness is never maudlin. But nor are its most sorrowful and strongest sentiments disguised. Pity not plaintiveness. Regret and depth not reminiscing or meandering. Technically, the choirs' approach is impeccable. Every note is clear and clean; yet the singing is expressive and of a sustained honesty that at times amazes; and always delights.

None of these qualities ever comes close to blurring the crystalline distinctiveness which such a romantic work of faith needs to be convincing and authentic. Even when one almost feels that the singers are humans singing rather than singers aiming to express humanity – such as during the ecstatic "Great Doxology" [tr.12], their technical grasp of the words and their settings never wavers. It's not that they are letting us know that they still have something in reserve (for their command of dynamic is superb throughout this recording); rather, that they have so completely understood the idiom that they are able to embody its musical and confessional impetus without surrendering, or appearing to "lose" themselves. This perhaps is the greatest strength of all on this recording. The essence, maybe, of the Icon.

The acoustic of the Church of the Transfiguration, Massachusetts, offers just the right amount of resonance without swamping the performers' projection of the ecstatic and uplifting in Rachmaninoff's passionate score with spurious atmosphere. There is a real sense of space; but it's not a space in which merely to feel larger than one actually is. The glossily-produced and handsomely-illustrated 28-page booklet that comes with the CD is excellent – and almost worth buying this set for alone. It contains a perceptive essay by Jermihov on Rachmaninoff's position in twentieth century music and the role of his Russian roots in motivating his compositions; and the full texts in Cyrillic, Roman transliteration and English. There is also a carefully-constructed guide to the sequence of the Service; and bios of the performers. The simpler, four-side insert contains a track listing and credits.

Even though you may be happy with the other recordings of the All-Night Vigil (such as the benchmark ones with the Latvian Radio Choir under Sigvards Klava on Ondine 1206 and the St. Petersburg Chamber Choir under Nikolai Korniev on Decca 002260702), there is much about this present one on Paraclete – particularly in the glorious sound of SACD – to recommend that you add it to your collection. Immediately.

Copyright © 2017, Mark Sealey