The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

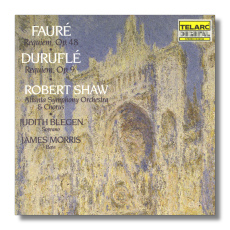

Requiems from France

- Gabriel Fauré: "Messe de Requiem" Op. 48 (1900)

- Maurice Duruflé: Requiem Op. 9 (1947)

Judith Blegen, soprano

James Morris, bass

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Shaw

Telarc CD-80135 DDD 74:23

Mozart's Requiem, even though not entirely by him, seems to me a perfect setting of this rather difficult text. The majesty and terror of death may storm through many of the "Dies irae" sections, but there's also the incredibly sweet consolation of passages like the "Recordare." Still, the total effect is a grand one, like the Berlioz and the Verdi, both of which take a more theatrical, even grand guignol, approach. Nevertheless, the monumentality of the three make them all more than a bit remote. I can't actually imagine playing any of them at the funeral of someone I knew, any more than I can imagine the Sistine Chapel ceiling in someone's living room. These are, to a large extent, public, rather than private works – suitable to the events of a concert hall or a national commemoration.

Still, we grieve more often privately than publicly. What music speaks to that? Certainly, the Fauré and the Duruflé do. Both, significantly I think, cut the "Dies irae." The latter has unquestioned theological importance, but it seems way off. At a funeral, we think of the one we miss and how much, not of Christian Ragnarok. The two composers concentrate on a vision of serenity in the presence of death and, interestingly enough, in the presence of heaven. They also limit the soloists to soprano (or high mezzo) and baritone, and use them in roughly the same way – the soprano as an emblem of innocence, the baritone of anguish. In fact, the two works share so much, that – although I have no scholarly evidence to support me – I've always felt that, to a great extent, Duruflé modeled his work on the older man's.

There are, however, plenty of differences. Duruflé takes almost all of his themes from traditional chant. Fauré bases his music on transfigured gestures of the funeral march and Bach Préludes, probably filtered through such luminaries as Gounod and Saint-Saëns. Although I admit the beauty of both works, I find the Fauré more interesting musically and more difficult to carry off. As a chorister, I've sung both. Despite the serene tone of the Fauré, it never lets the singers coast. The Duruflé is far more considerate.

Fauré either wrote or approved three versions: the original, for small forces, conceived as an actual service; one for slightly larger forces (1893); and one for still larger forces, probably not orchestrated by Fauré himself. Until very recently, mainly the last version got performed and recorded (see, for example, the André Cluytens account on EMI CDC-7 47836 2, with de los Angeles and Fischer-Dieskau). British composer John Rutter essentially rescued the 1893 version from oblivion and actually made it more popular. Certainly it's the version done here.

In terms of sound alone, the Shaw performance stands among the best. The Atlanta Symphony plays clearly and with a warm, burnished tone, fitting the music to perfection. The Atlanta Chorus sounds better than most recent Shaw groups, recalling the glory days of the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus of thirty years ago, when Shaw led it. It's yummy, it's creamy, it's rich, without lying around like a heavy meal. For a large chorus, it's incredibly flexible, rhythmically speaking. The one disappointment is, in my opinion, the tempo of the opening movement, which Shaw takes too fast. Fauré described it as a lullaby, and after the hint of the last trumpet and the whispers of awe from the chorus, the tenors sing what amounts to a Romantic dead march, suffused with incredible tenderness. At what I consider the proper tempo, it's hell to sing. The lines go on forever, with very few, very telling notes, and almost no opportunity to breathe. Cluytens's classic account, despite its butchered transfer to CD and a worse choir, at least has the tempo. I dwell on the first movement because its position alone gives it rhetorical importance in the work as a whole.

That's really my only complaint. Shaw's reading gives you one gorgeous moment after another, and the Requiem moves in a huge arc from beginning to end besides. Among the high points, William Preucil's violin solo in the "Sanctus" stands out, singing with great sweetness, and just as important, the choir takes an essentially uninteresting theme and intensifies the line. My favorite single moment in the Requiem is the ravishing enharmonic modulation at "Lux aeterna," and Shaw raptures me out here. The soloists, Blegen and Morris, overcome certain native disadvantages. The young Blegen had the sweetness of voice for the part. She's grown older (as have we all) and has lost some of that, but fortunately she never completely relied upon it. Her phrasing, if anything, has gotten even better, and her intonation still rings true. James Morris is simply the best soloist I've heard in the part, and I haven't forgotten Fischer-Dieskau, who in comparison sounds too heavy in Fauré. Morris, however, also has more vocal weight than a true Fauré baritone (the voice for which the composer wrote most of his songs). Fauré just about invented the emotional affect of this voice – refined and "at the listener's level," rather than a god, a king, or a wandering poet. Morris, on the other hand, has become one of the great Wotans, but he manages to lighten considerably without losing steel in the vocal line. He phrases gorgeously and with fantastic subtlety. I'm not sure such a performance would go over – that is, make itself heard – in the concert hall, but it's wonderful in recording.

The Duruflé also exists in at least three versions: for organ; organ and a small instrumental ensemble; organ and full orchestra. Apparently, you can also hear it with or without soloists. Shaw here assigns all the solo lines to the appropriate choral section. I didn't feel the absence, probably because the chorus does just fine, shaping a line with the lights and shadows of a soloist. Again, the performers play the music as if they love it. My one quibble lies in the "Lux aeterna," where the canonic entries between chorus and solo flute come off slightly jagged, with the flute surprisingly dragging a bit.

Telarc's sound is its usual dazzling.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz