The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lees Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

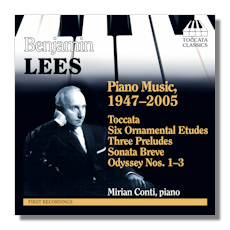

Benjamin Lees

Piano Music, 1947-2005

- Toccata

- 6 Ornamental Etudes

- 3 Preludes

- Sonata Breve

- Odyssey

Mirian Conti, piano

Toccata Classics 69 71:39

Summary for the Busy Executive: Steel and stillness.

The old CRI recording label made it its mission to record those American composers who didn't get recorded. As a teen, I learned a lot of American music through those LPs. However, they didn't have the best production values. Very few people recall them fondly for their sound, the great album covers, front-rank performers, or even sensible programming. Very often, one got a hodge-podge of pretty much unrelated work. On one such miscellany, a piece leapt out at me: the Prologue, Capriccio, and Epilogue of Benjamin Lees. I'd never heard of Lees, let alone his music, but he instantly became someone whose music I looked for.

I should say that at that point, Lees represented for me the musically far-out – at least, the farthest out I was willing or even knew to go. After all, Schoenberg was then terra ignota to me. I see Lees now, more than forty years later, as beyond conservative or progressive – rather an individual. In a cultural environment eager for the next novelty, he has continued to do his own thing – a dramatic neoclassicism, free of Stravinskian pastiche, darker than Piston, more direct than Diamond.

Lees, however, didn't spring from nowhere. He studied formally in California with Ingolf Dahl and Halsey Stevens, among others. It wasn't a happy fit, and later Lees began a remarkable apprenticeship under George Antheil, who taught him free of charge. I suspect that Antheil didn't concern himself with basic technique, but rather helped discuss and dissect the scores Lees was writing at the time. It says much for Antheil that his apprentice's music sounds nothing like his own. On the other hand, I doubt that anyone could have turned Lees into a clone. He has always struck me as someone who has to discover for himself.

I've not heard much of Lees' very early music, before Antheil, so I can't talk really knowledgably about Antheil's contribution to Lees' growth. In this regard, I may read too much into the Toccata from 1947. Lees talks about how it typified what other composers wrote at the time. Essentially, it takes off from Prokofieff and perhaps a bit of Bartók. However, beyond that lies something individually striking: a real feeling for form and for saying exactly what one means, without static. I should say that, pace Lees, perhaps he absorbed something from Dahl and Stevens after all, since the same kind of clarity also occurs in their music as well. Lees also writes idiomatic piano music and has produced a healthy bit of it, with at least three concerti and four sonatas, as well as substantial sets of pieces. Of his piano works, I first got to know the fourth sonata from a Columbia LP of Gary Graffman's, back when the label occasionally issued a modern work written after 1950, other than one by Bernstein or Copland. The sonata kept company with a Prokofieff sonata and, as I recall, the Bartók Out of Doors and held its own. Lord knows how or even whether Graffman had to fight the A&R guys, but it was certainly one of my favorite discs. I hope somebody made money.

The 6 Ornamental Etudes (1957) contain a lot of what makes Lees such an original. Unusually, the composer makes etudes out of, at bottom, ornamental figures and elevates something normally considered superficial or added-on to primary interest. Furthermore, like Chopin, he makes real music out of them as well. The etudes not only concern certain piano techniques, but modes of expression. For example, the extraordinary second etude – much of it a single line of music – demands that the performer get the piano to sing. Furthermore, each item, despite its brevity, conveys something deeper, without either inflating a trivial idea or short-changing a profound one. The longer you listen, the more they seem part of a whole. One or two all by themselves seem less than they do as members of the group. The range of emotion is big as well, and the emotions complex. The third etude emits a peculiar atmosphere, like hearing an abandoned wrist watch ticking away in an otherwise quiet room. The finale reminds me a lot of stride piano in its finger-energy, regardless of what Lees had in mind. A wonderful set.

Lees wrote the 3 Preludes for Joseph Bloch, who championed the Piano Concerto #1 (his performance available on Pierian 10). Like the Ornamental Etudes, this set means more than it says. The first prelude sandwiches unsettledness between proclamation (like the opening to the Bach Toccata and Fugue in d), while the second reverses it. The third has a more dramatic shape, a confrontation between two fairly tumultuous ideas.

The last two items on the program show the most ambition. The Sonata Breve is in fact a large sonata movement (12 minutes long) with, as Lees puts it, some "surprises." In general, its structure follows first subject group, second subject group, development, and recap (not strict), with the first subjects declamatory and agitated and the second subjects lyrical. However, the real interest is again the way the musical ideas bump and jostle one another and how they get transformed in the process. There's a concerto "feel" to the movement as well, at one point toward the end, a section analogous to a cadenza. The main idea is a call to arms followed by driven triplets. Lees gets a lot of mileage out of the triplet idea, and in the exposition the theme changes shape as it goes along, the rough corners getting knocked off until you have something close to diatonicism. The triplet drives much of the movement along, until the thematic climax, where Lees straightens out the triplet into duple time – a particularly satisfying outcome and a way to release the accumulated energy.

Lees wrote the three movements of Odyssey – designated "No.1," "No. 2," and "No. 3" – decades apart (the first written for John Ogdon and the last two for Mirian Conti) but grouped them under one heading. Do we consider them a whole or separable items? I can see it either way. All three span quite a stretch, as befits the title. All three share a general, uneasy mood. As opposed to Lees' usual iron logic and mastery of classical form, they ramble, moving associatively, albeit coherently, from one idea to another. For my money, the material becomes more concentrated from the first piece to the last. We start with something very much like classical motives in the first, but despite some neat transformations, motific manipulation takes a back seat to exploration of piano textures. Instead of growing something like a sonata or even a Wagnerian-symphonic form, it's as if the composer strings his ideas together like bits of colored beads. Lees leaves the security of classical form for a sole reliance on his ear. The second Odyssey takes texture much further, into an exploration of ornament. Most of the ideas in this piece reduce to a descending half-step, elaborated in various ways. It says a lot for Lees' invention that he keeps a tight grip on a listener's interest. The third part of the collection is in many ways the strangest of all, with an atmosphere similar to what Alice found in the woods. The logic becomes even more dream-like and the major unifier is variations on a texture (rather than a theme) of broken octaves. Lees risks much over such a long haul. I'd bet that when he began the piece, he had only an inexact idea where or how he'd end up. However, he has mastered musical rhetoric to such an extent that he's internalized the sense of musical time and how to shape it. Lees mentions the influence of Surrealism on his work, but to me he's closer to a sculptor who continually works the clay in his hands until he finds a shape to satisfy him.

Lees' piano music has obviously attracted great champions. I know best the work of Ian Hobson, heard in the second piano concerto (Albany TROY441) and on a disc of more of Lees' solo work (Albany TROY227). Argentinean-born Mirian Conti, an artist new to me, does a bang-up job. Her fingers not only mold the steel and fire of Lees' idiom, but she has a firm grasp on what usually comes down to complex structure. Her control of loud and soft is superb, capable both of sudden spikes without banging and smooth crescendo and especially diminuendo. One can see why Lees wanted to write for her. One of my favorite CDs this year.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz