The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bartók Reviews

Berlioz Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

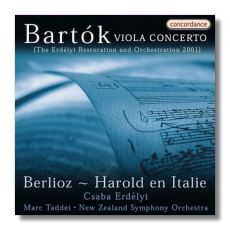

Bartók / Berlioz

Viola Concertos

- Béla Bartók: Viola Concerto (ed. Erdélyi)

- Hector Berlioz: Harold en Italie

Csaba Erdélyi, viola

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra/Mark Taddei

Concordance CCD03 61:24

Summary for the Busy Executive: Revelation.

Bartók wrote his last three orchestral works – the Concerto for Orchestra, the Piano Concerto #3, and the Viola Concerto – under the death sentence of cancer. The Concerto for Orchestra and the Viola Concerto, at least, were commissioned: the first by Koussevitzky, the second by Scottish violist William Primrose. Bartók completed the Concerto for Orchestra. He then worked hard on the third piano concerto, since he wanted to leave a vehicle from which his pianist wife could earn a living. In the meantime, Primrose, who had paid Bartók the princely sum of $1000, began to worry about the work's completion and asked after it. Bartók replied cryptically: the work was "composed"; all he needed to do was the "mechanical task" of writing it out. The composer also went over his sketches with his friend, Hungarian-American composer Tibor Serly. He died shortly thereafter. Primrose – to his credit – didn't ask for his money back.

It turns out that Bartók had left over a dozen manuscript pages of the concerto, as well as sketches and notes. The task for completing the concerto fell to Serly, who (like Süssmayer with Mozart) had the never-to-be-repeated advantage of consulting the composer himself. Until recently, this version alone has been performed.

Unfortunately, Serly, although a fine composer in his own right, was no Bartók, in several senses. The main one is that his own style was really nothing like Bartók's. It resembled more Kodály's, his teacher. Over decades, the Serly completion has seldom convinced me. It always took a rare great player to put it over, and even then it came across as the weakest mature piece Bartók ever wrote. It certainly doesn't sound like the other concerti. However, there are so few viola concerti – especially by major composers – that virtuosi seemed driven to perform it anyway.

Erdélyi apparently felt the same way. Unlike other violists, he did something about it. He studied a photocopy of the score for decades as well as other works by Bartók and Bartók's written remarks about his vision of the piece. It has paid off in ways that certainly exceed my expectations. For the first time, I feel like Bartók is actually in the room. The differences between Erdélyi and Serly become very quickly apparent. However, they differ mainly in the degree of focus and of the realization of Bartók's sound-world. Perhaps I should say that Erdélyi's realization fits my image of Bartók's music more snugly than Serly's. Bartók's sound is filled with pain. The accents go through you. Even in the brightly-colored moments, the colors are so bright, they hurt, like emerging from a gloomy room into sunlight. The contrasts are stark: dark-and-brooding leads to sudden explosions of energy. One also gets the sense of an unflinching gaze upon the argument at hand, a relentless, inexorable movement from here to there. Serly gives us something far more mellifluous and light-minded, without edges.

This recording replaces my previous two best recordings – Daniel Benyamini and Barenboim, and Yo-Yo Ma (on something called the alto violin, a "vertical viola") with Zinman. Erdélyi, a virtuoso certainly up to the technical demands of the piece, and he plays with intensity and fire. If I prefer Paul Silverthorne's playing, I must remind myself that he hasn't recorded this version, and that Erdélyi isn't exactly chopped liver. Taddei's New Zealand Symphony Orchestra has the piece down, with attacks crisp as fresh lettuce. Soloist and orchestra achieve wonderful clarity and fine ensemble.

The "filler" – and it seems strange to designate it this way – is Berlioz's Harold en Italie. It's an odd thing to put with the Bartók, and I would have gone with something like Hindemith's "Schwanendreher," but what the heck? The account is good, but not special, and I wouldn't recommend it if the Berlioz is what you really want. Nevertheless, the CD is essential for Bartók fans.

One little note: You may have to wait a while before this version generally replaces the Serly. The version is forbidden in most of the world, except for Australia and New Zealand, the only two countries that didn't sign the extension of copyright from 50 to 75 years following the author's death. At this point, in my opinion, the only people who win anything from this decision are publishers who've had, after all, at least fifty years to make money from the bones of a dead man. Scholars, students, and music lovers worldwide lose.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz