The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Howells Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

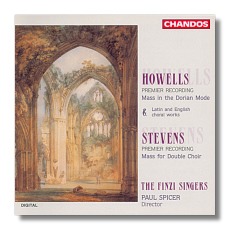

20th-century British Sacred Music

- Herbert Howells:

- Mass in the Dorian Mode

- Salve Regina

- O salutaris Hostia

- Sweetest of sweets

- Come, my soul

- Antiphon

- Nunc dimittis

- Regina caeli

- Bernard Stevens: Mass for Double Choir

The Finzi Singers/Paul Spicer

Chandos CHAN9021 70:32

Summary for the Busy Executive: Strong performances of serious choral repertoire.

Most people know Herbert Howells primarily as a church composer, although he wrote chamber and orchestral pieces as well. He considered himself a follower of Vaughan Williams, having heard the première of the latter's Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and, indeed, having studied with Stanford, one of Vaughan Williams' primary teachers. I must confess up front that I greatly prefer his instrumental work and his magnificent solo songs to his choral pieces, even though he wrote a number of very beautiful ones. For me, his best is his unconventional Requiem, written in the anguish he suffered at the death of his young son. The late Take him, earth, for cherishing, on the death of President Kennedy, recalls some of that pain. I've a soft spot for the St. Paul's Service, superbly fitted to the acoustics of the building he composed it for.

Howells has the technique, at least, of a master choral writer. The problem is that his choral idiom, though highly refined, isn't particularly memorable. One – unfairly perhaps – keeps comparing him to Vaughan Williams, Holst, or Finzi, beside whom he usually looks rather colorless. Where one sees in, say, Vaughan Williams' choral work strong, dramatic gestures and contrasts (I can't think of too many composers who can get as much as Vaughan Williams out of a single unison line of music, for example), Howells usually comes across as a pastel wash. One sees this most readily when one considers Howells's Herbert settings besides those of Vaughan Williams. Both men set Herbert's "Antiphon," Howells in 1977, Vaughan Williams as the final movement of his 1911 Five Mystical Songs. Howells's settings stand among the best of his output, and considered on their own, get the blood going. But they do lack the direct expressive vigor of his hero – the ability to turn an almost too-simple musical idea into something powerful.

One can say much the same for the early Mass in the Dorian Mode. Howells wrote it in 1912 for Richard Terry, music-master of Westminster Cathedral, who did probably more than anyone in England to revive the sacred music of the Renaissance in general, and the English Tudor composers in particular. Stanford encouraged all his students to hear the cathedral choir. "Palestrina for a penny" was his motto, referring to the carfare from the Royal College of Music to Westminster. Patrick Russill's liner notes point out that Howells's mass predates Vaughan Williams' Mass in g-minor by over a decade and, in so doing, again puts a fine work in the shade of a flat-out masterpiece. The Howells mass is what you'd expect from a Stanford pupil working in the modes. The Brahmsian Stanford himself, late in life, studied modal counterpoint, which he employed in a double mass for Terry – now lost – and in the oratorio Eden. Clearly, Terry and the Edwardians' nostalgic revival of the Tudor era had a palpable effect. Howells's counterpoint is assured, but he can't resist putting in extra filigree or post-Brahmsian chords. In general, the most successful movements – the Kyrie, Sanctus, and especially the three-voice Benedictus – are the most spare, and one can hear the intertwining of the separate lines. Vaughan Williams' Mass in g-minor, on the other hand, is less contrapuntally "correct" and more expressive. The revival of Renaissance modal counterpoint, although a touchstone of the work, doesn't become the end. Indeed, an early critic observed more parallel fifths than any work "since Perotin." This should tip us off to Vaughan Williams' lack of concern with imitation or revival. He actually creates something new and strongly individual – a work that by touching both Tudors and contemporaries transcends both times. Howells's mass, however, remains of its time – Georgian nostalgia. Again, Russill's liner notes do Howells no favors by pointing out that his mass precedes Vaughan Williams'. In art, it matters less who goes first than who does best.

If you don't know anything by Bernard Stevens, you've missed a rare treat. Everything I've heard I at least respect, and most of it knocks me over. I consider him a rough British equivalent of the American Walter Piston. Both composers turn out architecturally beautiful and powerfully moving music. Apparently, Stevens wrote slow and careful, so his catalogue remains small. The early Mass for Double Choir (1939) stands with the best of modern British choral music. This masterpiece can stand beside the monuments of Vaughan Williams, Holst, Britten, Elgar, and Walton without becoming dwarfed or washed out. It's also a bit of an anomaly in Stevens's output. As far as I know, Stevens was an atheist, or at least an agnostic. The work answers the question of whether a non-believer can write a successful sacred work resoundingly in the affirmative. Stevens wrote it apparently as a composition exercise at the Royal College of Music. Like a lot of his music, he didn't push it forward to performance or publication, and his widow found the manuscript among his papers. She suggests that this reluctance may have stemmed from Stevens's disappointment with Christianity as a force to combat Fascism and his subsequent embrace of left-wing politics. Although not yet possessing the sound of the mature Stevens, it's an astonishingly accomplished work for a twenty-three-year-old. In its own way, it hearkens back to the Vaughan Williams mass, even if the part-writing exhibits fewer quirks. Significantly, I think, it lacks a Credo movement. The Credo usually stumps composers, probably because it lacks the imagery and the passion of the other mass movements. It hasn't the archaism or the pain of the Kyrie, the heavenly blaze of the Gloria and Hosanna, the humility of the Benedictus, or the blessing of the Agnus Dei. It's as much a political statement – a remnant of the doctrinal wars of the first millennium – as a statement of personal faith. Not even the believing Catholic Poulenc set the Credo in his mass. My one carp with the piece is that it relies a bit too heavily on antiphony, a natural device for two choirs. However, the cool beauty of the whole shows up that criticism for the pickiness it is. As I say, it can stand in the company of the Vaughan Williams mass or the Britten Hymn to St. Cecilia without bleaching out. It is itself a monument of British choral music, and to think that it took over half a century to come to general notice. I can't recommend this piece strongly enough.

Spicer and the Finzi Singers constitute British choral royalty. In a country chock-full of superb small choral ensembles, they stand out, along with the Tallis Scholars, the Sixteen, the King's Singers, and one or two others. These works demand top-of-the-line choirs with a serious commitment to "hard" music. The Finzi Singers are that good and that dedicated. Their sound and blend is superb. They yield a little to the Dale Warland Singers in clarity of parts, but who cares? They're still wonderful. Their intonation is dead on. Spicer makes musical sense of very complex works and has trained the choir to deliver. Anybody interested in choral singing should pick up this disc.

Upsetting postscript: With the imminent disbanding of the Dale Warland Singers, the United States loses its best group. Furthermore, American church and school choirs have been dumbing down repertoire for so long in the name, I suppose, of non-elitism that I might bet against finding ten choirs in the country that could pull these pieces off. It means, of course, that few will recognize first-rate music, because fourth-rate music is all most people know. The presumption of elitism not only insults the intelligence of people ("I understand it, but they won't") but actually damages the culture. How long Britain will be able to hold the fort is anybody's guess.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz