The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bax Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

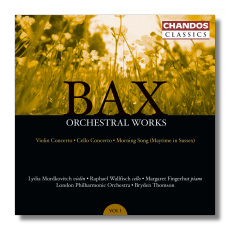

Arnold Bax

Orchestral Works, Volume 1

- Concerto for Violin & Orchestra

- Cello Concerto

- Morning Song (Maytime in Sussex)

Lydia Mordkovitch, violin

Raphael Wallfisch, cello

Margaret Fingerhut, piano

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Bryden Thomson

Chandos CHANX10154 77:18

Summary for the Busy Executive: Major work from a forgotten composer.

The opening volume in Chandos's series of Bax's orchestral music (minus the symphonies) concentrates on works for soloist and orchestra. The series has reached its ninth volume, by the way.

Considered one of the great English composers in his own day, Bax has pretty much slid into obscurity outside Britain. It's tempting to blame the changes on the musical scene after World War II, but in truth Bax's music had begun to fade by the late Thirties, despite his becoming Master of the King's Music in 1942. Vaughan Williams, Walton, and Britten – and slightly less prominent figures like Tippett, Bliss, and Rubbra – had superseded him with a more aggressive Modernism. As he grew older, he composed less and less. Chandos has made an heroic effort to bring him back by issuing recordings of all the symphonies, orchestral music, piano music, and possibly chamber music.

I consider Bax's music well worth reviving: an interesting mix of late Romantic and Modern, superb handling of the orchestra, and a uniquely complex counterpoint resulting from his orchestral sonorities. Bax intended his 1937 violin concerto for Heifetz. Heifetz rejected it, for some reason. No one ever accused Heifetz of perfect taste, especially in modern music, but, really, he spat on a masterpiece and what's more, one perfectly suited to his musical point of view – big, Romantic, heroic. The concerto exhibits unusual architectural features. The first movement, subtitled "Overture, Ballad, and Scherzo," comes across as a three-movement violin concerto in miniature, with each section based on the same general idea. The idiom, vigorous and athletic, shows Bax's participation in British Modernism. As for those used to Bax's music of the Celtic Twilight, this movement especially will surprise them.

Critics have tended to treat Bax's music after the Sixth Symphony (1934) as inferior. I find no falling-off myself, although the inspiration differs. The later work, like the violin concerto, still sings passionately, but more efficiently and with less Sturm und Drang. I look on it as having fewer but more telling notes. One marks less of the emotional excess than in a score like the Second Symphony (1926). I have no way of really knowing, but I suspect the following. Bax's musical inspiration was usually tied to his physical surroundings. He responded to landscape. Most of the work seen as characteristic evoked his stays in the west of Ireland. As he grew older, he went to Ireland less and less and finally moved to Sussex. For me, the slow movement broods less than Bax's usual and instead glows with a rare serenity. In A-B-A song form, it begins with an ecstatic climbing theme, a cross between Delius and Vaughan Williams' Lark Ascending, and moves to a middle section which, as Lewis Foreman's liner notes keenly point out, foretells the Forties "Mozartean" works of Richard Strauss. The sonata-rondo finale treats mainly two ideas – one light and fleet, and the other a lush waltz, slightly reminiscent of a theme from the Sibelius violin concerto. This movement brilliantly glitters and entertains, obviously designed to please the crowd.

The 1932 Cello Concerto was written for Cassadó. Somehow, it seems to me a smaller, more intimate work than the Violin Concerto, but then the later score aims for grandeur. Certainly, Bax can get huge sonorities when he wants to from his (reduced) orchestra in the Cello Concerto. Bax solves the problem of how to let the cello through the orchestral texture, often by accompanying the soloist with just a few instruments or by keeping the cello on top of the massed strings (Dvořák's tricks), but to say that leaves out Bax's genius for finding original sonorities. Instead of contrast mainly by dynamic, he achieves drama through color. For me, the musical argument is less focused than in the Violin Concerto. The first movement is a kind of "free ramble" with four ideas. It coheres, but it doesn't grab you so tightly. It's less compelling than the opening of the Violin Concerto. The slow second movement, my favorite, shows more of Bax's orchestral wizardry, and from the opening bars. Believe me, you haven't heard sounds like these from the standard orchestra, and they're all beautiful, rather than bizarre. If I pick nits, I'd say that the main theme almost suffocates in late nineteenth-century filigree, but the harmonies and sonorities belong entirely to the Modern era. The finale begins with a somewhat waspish idea. As the movement proceeds, one quickly realizes that Bax takes his pared-down orchestration to extremes. At times, nothing accompanies the soloist, and yet Bax maintains the illusion of full-bloodedness. The movement, probably the most dramatic of the three, is not the conventional rondo, but an A-B-A structure which creates a narrative of "taming" that first theme, through a long, languid, almost "Neapolitan" middle section. The recapitulation shows that first theme finally mellowed into major.

As Master of the King's Music, Bax was assigned "occasions" to compose for. Princess Elizabeth (as she was then) received a twenty-first birthday present of Morning Song, for piano and small orchestra. It doesn't storm the heavens or, for that matter, rail against fate. It's a quietly lovely piece, Bax's take on British Pastoralism, and there's not a folk-song or overt folk influence in it. One feels a quiet Wordsworthian joy in the presence of nature, very English. Its modest scale works against it in the concert hall, but, boy, it's just made for recording. I hope this is the first of many.

I don't count myself a fan of the late Bryden Thomson. I find his outlook in general too sweet for my taste, and I'd love to hear what Vernon Handley, for example, or Norman Del Mar would have made of the concerti. Nevertheless, Thomson gives you an idea of the injustice of their neglect, and he's spot on in Morning Song. The thickness and, in places, dullness of Chandos's sound surprised the hell out of me, but I guess even Homer nods. At any rate, it's not terrible enough to scotch a guilt-free recommendation.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz