The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Barber Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

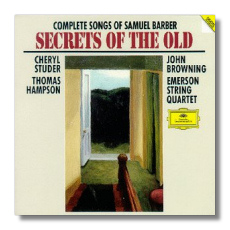

Samuel Barber

Secrets of the Old - Complete Songs

- A Slumber Song of the Madonna (1925)

- There's Nae Lark (1927)

- Love at the Door (1934)

- Serenader (1934)

- Love's Caution (1935)

- Night Wanderers (1935)

- Of That So Sweet Imprisonment (1935)

- Strings in the Earth and Air (1935)

- Beggar's Song (1936)

- In the Dark Pinewood (1937)

- Songs (3), Op. 2 (1927-34)

- The Daisies; With Rue my Heart is Laden; Bessie Bobtail

- Dover Beach, Op. 3 (1931) *

- Songs (3), Op. 10 (1936)

- Rain has Fallen; Sleep Now; I Hear an Army

- Songs (4), Op. 13 (1937-40)

- A Nun Takes the Veil; The Secrets of the Old; Sure on this Shining Night; Nocturne

- Songs (2), Op. 18 (1942-3)

- The Queen's Face on a Summery Coin; Monks and Raisins

- Nuvoletta, Op. 25 (1947)

- Melodies passageres, Op. 27 (1950-51)

- Puisque tout passe; Un cygne; Tombeau dans un parc; Le clocher chante; Depart

- Hermit Songs, Op. 29 (1952-53)

- At Saint Patrick's Purgatory; Church Bell at Night; St. Ita's Vision; The Heavenly Banquet; The Crucifixion; Sea-snatch; Promiscuity; The Monk and his Cat; The Praises of God; The Desire for Hermitage

- Despite and Still, Op. 41 (1968-69)

- A Last Song; My Lizard; In the Wilderness; Solitary Hotel; Despite and Still

- Songs (3), Op. 45 (1972)

- Now have I Fed and Eaten up; A Green Lowland of Pianos; O Boundless, Boundless Evening

Cheryl Studer, soprano

Thomas Hampson, baritone

John Browning, piano

* Emerson String Quartet

Deutsche Grammophon 435868-2 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Hampson does swimmingly. Studer out of her depth.

This set advertises itself as the "complete" songs of Samuel Barber. As far as the published songs go, this is true. However, Barber wrote over a hundred songs and published only thirty-eight (not thirty-six, as the liner notes claim). The program here consists of slightly more than thirty-eight songs, so it obviously includes some unpublished ones. Just don't be surprised when other CDs of Barber songs not on this set show up, as I'm sure they will, eventually.

Barber had song practically in his DNA. His maternal aunt was the American opera star Louise Homer, and his uncle Sidney Homer had a strong reputation as an art-song composer. Barber even trained as a singer while a student at Curtis, coming out with a professional, although stylistically old-fashioned light baritone. Since live song recitals - other than Winterreise, Die schöne Müllerin, and opera arias (which don't really count) - have largely gone the way of horsehair sofas, so has the output of such once-beloved luminaries as Sidney Homer, Oley Speaks, John Alden Carpenter, John Ireland, Carl Loewe, Edgar Stillman-Kelley, Richard Hageman, and John Duke. The kind of eclecticism once featured in the programs of Lawrence Tibbett, John McCormack, and, latterly, Jennie Tourel, Donald Gramm, and Beverly Sills we simply have, by and large, lost interest in.

I've always categorized song by context, aim, and function. Just as one distinguishes among dramatic, narrative, and lyric poem, I believe that one should distinguish among aria, scena, and chanson or Lied. A cycle like Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire clearly bursts the confines of the self-contained song, just as Mahler's settings in Das Lied von der Erde do – not really opera, and more than Lied. I regard the distinction more than a matter of forces involved. After all, Schubert's setting of the Cathedral scene from Goethe's Faust, involves merely two singers, optional unison chorus, and a piano, while something like Strauss's Op. 68 (Sechs Lieder), even though it involves singer and orchestra, really loses nothing essential when performed in its piano version. The Lied corresponds to the lyric poem – an intimate and self-contained expression. A great song-writer doesn't necessarily write great operas, just as a great opera composer doesn't necessarily write great songs. Wagner's Wesendonk Lieder, lovely as they are, still have more modest aims than, say, the Prize Song in Meistersinger, while Mahler, a master song-writer, didn't seem to have the composer's instinct for opera, even though he made his reputation as an opera conductor.

Barber is one of the lucky few to have excelled in all three types of songwriting. Despite the critical whipping his major opera Antony and Cleopatra got its first time out (a première sunk by an elephantine production conceived by the grandiose Zeffirelli, who hadn't the brains to even measure the stage space before he built sets), it turns out that the work is indeed a major item in his catalogue. Above all, it works as drama, not simply a collection of pretty tunes. Barber also wrote scena - the surreal "Nuvoletta" (a passage from James Joyce's Finnegans Wake), the early "Dover Beach" (more below), the late Andromache's Farewell, and the stunning masterpiece Knoxville: Summer of 1915. The rest stand very much in the tradition of German Lied and French chanson or mélodie.

Ned Rorem, even while acclaiming Barber as a "national treasure," nevertheless complained of the "facelessness" of Barber's songs. I have no idea what he's talking about. If he means that Barber appropriated other composers, it's true but trivial. Nobody, not even Rorem, creates from scratch. I think it's true to say that in Barber's songs one finds a certain reserve, an artistic "cool," even at climactic moments, that contrasts with the "go-for-emotional-broke" of someone like Mahler or Mussorgsky. When Barber misfires, you get a well-crafted - even genteel - song you don't really care about. When he connects, he gets inside you, just because he has held something back; you seek the song because he hasn't handed you everything. In this respect, he reminds me of Brahms.

Barber's studies as a singer profited him as a songwriter. More than many composers, he knew both how to get the most out of a singer as well as how to write considerately. A singer can make a grand effect with Barber's songs without tearing up the voice. Part of that effect also comes from his ability to sharply imagine the context of the song recital and to provide "nice groups" of songs. Furthermore, he chooses texts with a great feeling for literary quality as well as with great catholicity of taste. He read widely, and in several languages. I believe he was the first major composer to seek out the lyrics of James Joyce, and he did so throughout his career, early and late. A partial list of his writers includes the aforementioned Joyce, Agee, Stephens, Hopkins, Yeats, Prokosch, Horan, Rilke, Roethke, Graves, Neruda, and Milosz.

Many of Barber's songs have entered the standard repertory of just about every voice student, at least: "The Daisies," the Op. 10 songs from Chamber Music, "Sure on this shining night," "A Nun Takes the Veil," "A Last Song," "Solitary Hotel," and, for baritones with access to a string quartet, "Dover Beach." These are done - not all the time, since a vocal recital outside a conservatory is only slightly less rare than chicken navels - on those programs where Barber's songs are done at all. Nevertheless, even so one finds neglected gems, including major cycles, and I find myself wishing for even more enterprising singers. In that regard, a "complete" collection on CD allows you the pleasures of exploration.

Cheryl Studer and Thomas Hampson have hot careers right now, and John Browning has long acquaintance with Barber's music. The Emerson put out a very fine performance of the Barber String Quartet. How do they fare here?

Browning goes beyond the usual accompanist. He of course has technique to burn, and while Barber's songs don't call for a virtuoso pianist, Browning nevertheless puts his skills to the subtle variance of color and touch. Hampson has struck me as inconsistent. On the one hand, he can sing superbly, so well it's just about unearthly - as in his Mahler recital on Teldec 74002. On the other, he can be incredibly annoying, mistaking vocal affectations for art. Here, he's simply the best. Not only does the mechanism work perfectly and the musical phrase fall with inevitability, but he communicates each poem and almost convinces you that singing is merely speech with notes. It sounds that natural.

Studer's got problems. Her voice is - at least here - too coarse for songs. She does better in opera. She sings consistently flat - within agonizing reach of the correct pitch without ever quite reaching it. Her tone is harsh. Compared to Hampson - a damning comparison, since you go from one to the other on the same CD - she does general-purpose declamation. If she actually understands the poems, she doesn't let on. She is Happy or Sad or in a Great Passion. She disappoints the worst in the Hermit Songs, Barber's longest cycle - gorgeous settings of poems by medieval Irish monks. Here, she competes with the young Leontyne Price and the composer himself at the piano (Sony MPK 46727), before Price's voice had darkened and acquired heft. In this classic performance, Price sounds fresh as a sweetwater spring, her phrasing flexible and giving the appearance of spontaneity. To be fair, Studer does better than usual in the Four Songs, Op. 13 - the group that includes Barber's hit "Sure on this shining night," his Agee warmup for Knoxville. Barber's considerable lyrical gift seldom soared higher, and yet the song happens, through much of its course, to be a diatonic canon at the third between piano right hand and voice.

Hampson competes with legends far more successfully. Barber recorded his own "Dover Beach" as a young baritone, and Fischer-Dieskau covered it in the stereo era. Hampson knocks both of them on their seats. I've never been all that fond of "Dover Beach," thus finding myself in uneasy disagreement not only with the composer himself, but with Ralph Vaughan Williams, who told the young Barber, "You got it," and confessed his own attempts to set the Arnold poem. To me, it's a holdover from the genteel late 19th century, and (since Barber wrote it while he still studied at Curtis) I suspect that Barber's teacher Rosario Scalero had a deadening, insistent hand in its idiom. Songs and piano pieces Barber wrote in the 1920s show far more enterprise. Despite my lack of affection for the piece, Hampson does so well that he almost convinces me. Barber's phrasing, like Studer's, is stiff as a starched shirtfront and the declamation pure whitebread. Hampson lets you know that this is, among other things, a great poem. Fischer-Dieskau tries to compensate for his accent by a fussiness with consonants, as if he's giving English lessons with a lecture stick and chart. Again, Hampson works a direct line to the listener, almost as in pure speech by a very good actor.

Hampson, Browning, and the Emerson win me over to this set. In fact, it may turn out to be one of Hampson's best.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz