The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

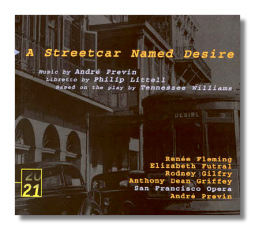

André Previn

A Streetcar Named Desire

- Renée Fleming (Blanche DuBois)

- Rodney Gilfrey (Stanley Kowalski)

- Elizabeth Futral (Stella Kowalski)

- Anthony Dean Griffey (Harold Mitchell)

Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera/André Previn

Deutsche Grammophon 459366-2 DDD 3CDs 58:10, 40:57, 62:46

It was only a matter of time before these American icons found their way into an opera. Lucky for them that the opera was written by André Previn, whose years of playing jazz and scoring films (to say nothing of maintaining a stellar career as a classical conductor/pianist) made him eminently suited to the task.

Although the opera is in three long acts, interest never flags. For listeners in the theater, an additional challenge is posed by the set, which remains the same throughout, and by the relatively small number of characters. (There is no chorus, no colorful crowd scenes, and certainly no opulent ballet.) As with the operas of Benjamin Britten and Samuel Barber, composers for whom Previn has not hidden his admiration in word and in deed, Streetcar is a 20th-century opera in touch with its 19th-century roots. There are a few real arias, primarily for Blanche, who is the focal point of the opera, vocally speaking. This must be an exhausting role, because she is hardly ever offstage, and it (and the opera) ends with a soaringly lyrical mad scene as she fantasizes dying with her hand "in the hand of some good-looking nice ship's doctor with a small blonde moustache," and then being buried at sea. Fleming's increasingly heavy voice seems right for this role, and she is a good vocal actress, suggesting the many layers (innocence, vulnerability, sexual predation) of Blanche's shattered personality. Like Alban Berg's Lulu, she really seems to be both sinner and sinned against.

Librettist Philip Littell (who has done a remarkable job condensing and refitting Tennessee Williams' original drama) asked Previn to set Stanley's famous cry of "Stella!" to music; Previn wisely declined. If the opera's vocal center is Blanche, Stanley seems to be bidding to take violent control of the orchestra. This sets up the tension that sustains the opera, and sets up the climactic rape scene (which reminded me a little of the corresponding scene from Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk). Surely it's no accident that Stella's brutish husband and Blanche's boorish brother-in-law doesn't partake in that European tradition, the operatic aria – Stanley has none to sing. Previn and Rodney Gilfry have the difficult task of setting Marlon Brando to music. Previn is perhaps more successful than Gilfry. The American baritone has a commanding stage presence and the right "look" for Stanley, and his voice, on the rare occasions when he is allowed to use it lyrically, is superb. However, Gilfry's accent is less successful than that of his colleagues, and he frequently sounds more like a fisherman from New England than a factory-worker from New Orleans. (A Streetcar Named Downeast, anyone?)

At the end of the opera, Stella's fate is only slightly less bleak than her sister's; at least she has a baby to care for now. Elizabeth Futral, whose other roles include Lucia di Lammermoor and Pamina, was a wise selection for this role. Her light and shimmery voice tellingly contrasts with Fleming's, and it suggests the state of dirty rapture that initially attracted her to Stanley, and the psychosexual hypnosis that has kept her with him this long. Harold Mitchell, also known as "Mitch," is the mama's boy who almost shares Blanche's self-delusion. Anthony Dean Griffey's blustering tenor is an apt mirror for this character's mounting but ineffectual panic.

With its mixture of sax-heavy blues and gnawing nostalgia, Previn's score is not unlike Alex North's music for Elia Kazan's 1951 film. True originality is infrequent in this opera. (One of the most striking sections is in Act III, Scene One, during which Previn depicts the intervals of passing time with music that sounds as if it has been electronically accelerated.) However, although one cannot praise Previn for breaking new ground, one can admire the strength and sincerity of his workmanship. Time will tell whether Streetcar will become a part of the international repertoire (how many new operas have?). In the meantime, there's no reason not to enjoy its steamy claustrophobia, and this new Deutsche Grammophon recording, taken from live performances, is an excellent snapshot of its lucky birth.

Copyright © 1999, Raymond Tuttle