The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

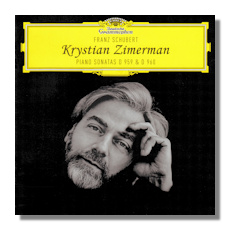

Franz Schubert

Sonatas for Piano

- Sonata for Piano in A Major, D 959

- Sonata for Piano in B Flat Major, D 960

Krystian Zimerman, piano

Deutsche Grammophon 47975885

Not published until ten years after Schubert's death, the three late piano sonatas (D958, 959 and 960) are the composer's last major works for piano. They were composed between the spring and autumn of 1828. On this outstanding CD from DG, Polish virtuoso Krystian Zimerman gives trenchant, poignant and technically brilliant accounts of D959 and D960 using a conventional piano fitted with a keyboard which he designed and built himself so as to sound more closely like one which Schubert would have known; and so presumably more capable of obtaining the sound for which he composed.

There is greater percussiveness for sure. Although this is no fortepiano. And the emphases are gentle and unobtrusive. The hammers strike a different part of the strings. This allows for a more sustained "singing" sound; and a lighter one. This takes less getting used to than you might think. The overtones are richer and yet may suggest an unfamiliar tuning. A couple of listens reveals a depth and sense of sonority which put these great works exactly where they belong. That is, on the cusp of the Classical and Romantic eras.

Zimerman's playing is crisp but never trite; incisive without insistence; precise but shot through with personality and spontaneity. At the same time it's full of feeling but never muddy; warm and colored yet lacking in superfluous emotional overlay. Above all, Zimerman uses his deep understanding of the architecture of each movement to make these special performances. These accounts of the Sonatas as a whole convey the mellow and almost valedictory nature which can typify Schubert's last works. The pacing, almost hesitant phrasing and comfortable tempi of the very end of the A Major's (D959) [tr.1] allegro is a case in point. The playing has the poignancy and energy of the "Moments Musicaux" with the pathos usually associated with (these) longer works.

By the second movement we are involved in the implied story which seems to unfold in surprisingly unexpected directions as Zimerman somehow exposes dimensions to the sonatas (four minutes or so into the same sonatas' andantino movement [tr.2], for instance) almost as if we are hearing them for the first time. Like Glenn Gould, Zimerman has that great gift of gently but unambivalently uncovering the totality of a work by concentrating on individual notes. And is of course aided in this by the clarity of this piano's sound.

A passage which perfectly illustrates Zimerman's approach is five or so minutes into the rondo finale of the A Major [tr.4]. The leaps and repetitions could so easily have lost all their power by being played stridently or with heavy-handedness. Yet Zimerman effortlessly achieves a balance between appearing to explore them with us (as if for his first time) and guiding us through something instinctively and with confidence. And does so with a magical balance of confidence and an almost unsolicited effervescence. But none of it out of place. One wonders how like to Schubert's own playing with its hint of extemporization this pure and sensitive approach of Zimerman's is. It's certainly persuasive here.

For Zimerman, the slow movements are amongst the "…saddest music I know". Yet at the same time, there is a summative quality which might – once you have identified it – be at odds with his humor (in the scherzi, for example) and even sit somewhat awkwardly with the revolutionary, or at least visionary, qualities of those slow movements in particular. Zimerman's taut playing consistently resolves the gulfs between resignation (and imminent death) and hope. He achieves this in part by the use of tempi which are flexible (which does not mean wayward) and which allow the music its head.

The qualities of transparency, care, depth result from insight into the music and a complete absence of the "dreaminess" which we often associate with these final works. Such an approach characterizes Zimerman's conception and execution. He has obviously prepared the works with much thoughtfulness after deciding (we learn) to find the courage – at 60 years of age – to revisit Schubert's last Sonatas. Remarkably, for all his command and meticulous transformation of technique into expression, he is clearly still in awe of Schubert's achievement… as he should be. The great strength of these accounts is that his invitation that we feel the same is one we can hardly dismiss.

Zimerman's playing of the sublime D960 is every bit as enthralling, profound, reflective and thoughtful. Yet the sense that he is contemplating the eternal (as Schubert surely was) never results in a loose, wandering or unduly speculative approach. He does take the opening movement [tr.5] very slowly; but its marking is molto moderato, which is taken to mean that the pianist should definitely temper any inclination to undue speed or to ignoring it. This Zimerman does in such a way that each note contributes to the phrase or sentence in which it finds itself without either hesitancy or ambiguity. There is great deliberateness. This has a rather unworldly result: perhaps a little like issuing a(n unexpected) warning in a slow and emphatic tone. But the authority here – and throughout the Sonata – is superb.

Indeed as the first movement progresses, the pace remains measured, and full of momentum. But it never loses definition. Again, you may imagine hearing phrases and notes never before heard. There is nothing heavy-handed or over-emphatic when it needn't be. At the same time, Zimerman retains control and conveys a sense of direction, both of which help to make this such an exciting performance. As the (also four movement) Sonata is revealed (for much of Zimerman's playing is revelatory), there is a certain inevitability to Schubert's melodies and harmonies. The development of his ideas and the gentle and overtly delicate ways in which he often reaches their apotheoses are also examined expertly. So, the impression which the music leaves on us as an organic whole is extraordinary.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Zimerman's approach is that he expresses this sense of contour, variety and at times the unexpected (through judicious use of the pause – for instance, in the last two or three minutes of the D960 first movement) in a very linear and transparent way. And again, the precise and sensitive way in which the pianist picks his way through the andante second movement is an example in making the intricate sound open and accessible. Once again, the solidity of the specially-built piano's timbre, definite responsiveness and timbre adds to the certainty which surely Schubert intended when contemplating the ineffable.

The acoustic of the Kashiwazaki City Performing Arts Center-Forêt in Japan is neutral and adds no color; so it happily and appropriately supports those aspects of Zimerman's playing which benefit from transparency and penetration. The short booklet consists of a brief interview with Krystian Zimerman by Jessica Duchen. His answers to her questions are revealing and convincing: he pulls out Schubert's anti-militarism; the way in which the composer seems to offer musical ideas without imposing them; and Zimerman's own professionalism and belief in his "right" to be an artist. If you're of the belief that you can never have too many interpretations of these amazing sonatas, in these by Zimerman you'll enjoy a beautiful balance between the bitter and sweet, and between nostalgia and hope.

Copyright © 2018, Mark Sealey