The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Holst Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

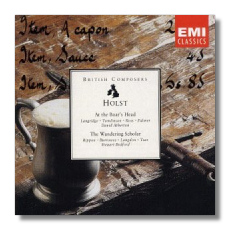

Gustav Holst

Chamber Operas

- The Wandering Scholar

- At the Boar's Head *

English Opera Group

English Chamber Orchestra/Steuart Bedford

* Men's Voices of the Liverpool Philharmonic Choir

* Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/David Atherton

EMI CDM 5 65127 2 75:44

Summary for the Busy Executive: Charming, but non-essential Holst.

Aaron Copland, in maybe his wittiest joke, once called opera "la forme fatale" - referring to the fascination the genre held for composers who, unlike Verdi and Mozart, didn't practice it regularly and who, in Copland's opinion, produced rather weak-kneed examples. Holst started or finished eight operas/operettas, only one of which has held (precariously) the stage - Savitri - and another - The Perfect Fool - survives in an instrumental excerpt. I've heard three Holst operas: Savitri and the two here. All of them suffer from their short length. Professional opera companies don't regularly mount "chamber operas," excepting, I suppose, Cav, Pag, and Il Trittico.

More than that, of course, bars their way. To some extent, he wound up with bad libretti - supposedly the flaw of his own libretto to The Perfect Fool - but Verdi has worse. More fundamental is the problem that he's not drawn to good libretti or to strong situation. Savitri deserves this charge the least, but one can't say that any of its personae are fully-drawn people. Furthermore, Trovatore probably has a worse libretto than any of Holst's operas, and it's infinitely more powerful. Holst isn't a particularly dramatic composer - that is, he's not all that interested in creating character conflict or even using his music to describe character - and in this he stands in sharp contrast to his friend Vaughan Williams. Every Holst opera I've heard is filled with character types - in The Wandering Scholar, the old man married to the young wife, the ardent young man, the comic villain - rather than with real characters. Holst always struck me as a composer of emotional reticence, shying away from strong display of feeling. I also suspect he had a terror of boring people, so he tends to speak clearly, directly, and in as few notes as possible. There are of course exceptions in his output, and those happen to be or belong to his most popular pieces. Nevertheless, when I think of typical Holst, I don't fasten on "Mars" or "Jupiter," but on "Saturn" and "Neptune." Despite this, each opera is a wonder of construction, the parts so seamlessly joined and the music flowing with such precision, one gets the aural equivalent of a Fabergé egg.

The Wandering Scholar, libretto by scholar and translator Helen Waddell, takes its story from a Chaucer-like farce. A young wife hustles her old husband out of the house so that she can meet her lover, a self-centered priest. Before wife and lover can do much, a poor young scholar shows up asking for food, and the priest drives him from the house. Again, before wife and priest get going, they hear the husband returning, and wife hides priest. Husband arrives with the young scholar in tow. They've met on the road, and the husband has decided to feed the young man. Wife says there's nothing in the house, whereupon the young man, under the pretence of telling a fantastic tale, exposes the food and the priest. Husband drives priest from the house and the opera ends with the husband rapping his wife (off-stage). Obviously, the interest here lies in the twists of the plot, and Holst's music drives the action forward. A neat opera, in many senses of the word, this lean music neither wastes notes, nor lingers over this point or that - and it sparkles, in the way of much of Holst's work in the Twenties, eg the Fugal Concerto.

At the Boar's Head comes over as a bit of a stunt. Imogen Holst, the composer's daughter, reports that her father was reading one of the Falstaff episodes in Shakespeare's Henry IV and realized that the speech perfectly fit one of the melodies in the collection by Stuart publisher John Playford. Holst decided to write an opera based on Playford and contemporary folk tunes. According to the liner notes, only three of the melodies come directly from Holst. The action centers around the imagined "catechism" of Prince Hal by his father, the king - with Falstaff and Hal switching off the parts. This is probably the best libretto Holst ever worked with, and yet the opera doesn't differ all that significantly in its effect from The Wandering Scholar. There are lots of words but to little effect here, even if they are by Shakespeare. Holst achieves primarily movement, but it's movement every which way. One doesn't get a sense of purposeful direction or, for that matter, the feeling that the narrative actually means something. The characters move like automata and remain as closed to us at the end as at the beginning. We can instructively compare Holst's Falstaff with Vaughan Williams' in John in Love. Compared to Holst, Vaughan Williams sprawls, or seems to, putting in Elizabethan, even non-Shakespearean lyrics to set smack in the middle of the action. As it turns out, however, these lyrical sections invest the characters who sing them with great depth. Holst's Falstaff is a chubby blowhard. Vaughan Williams' Falstaff, like Shakespeare's, contains, as the fat knight says himself, worlds - a coward, a bully, a braggart, but a man full of life and an affection for the weaknesses of others, as well as for his own. Furthermore, despite moments of brilliance, Holst doesn't use the tunes to very great effect. They tend to become simple pegs on which to hang words, and Holst's characteristic concision and horror of digression make very little stand out. His great strength as a poetic, lyrical composer works to his disadvantage on stage. Everything registers with the same level of intensity.

However, one gives thanks for performances like these, especially the orchestral contributions. The principals of The Wandering Scholar hoke it up, but the piece can take it. At the Boar's Head benefits greatly from John Tomlinson as Falstaff and Philip Langridge as Hal. Both clear the hurdles Holst has set and rise to real drama in the "catechism." I stress, however, that it's mainly them rather than Holst. Bedford delivers a clean, sprightly account of Scholar, but David Atherton, a horribly underrated conductor, does an heroic job of pulling the amorphous blob of Boar's Head into real shape and takes surprising advantage of the meager opportunities Holst gives him.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz