The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vivaldi Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

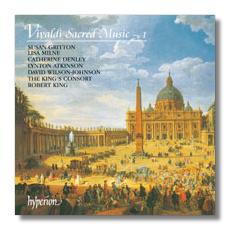

Antonio Vivaldi

Sacred Music, Volume 1

- Magnificat RV610a

- Lauda, Jerusalem RV609

- Kyrie RV587

- Credo RV591

- Dixit Dominus RV594

Susan Gritton, soprano

Lisa Milne, soprano

Catherine Denley, alto

Lynton Atkinson, tenor

David Wilson-Johnson, bass

The King's Consort and Choristers/Robert King

Hyperion CDA66769 62:42

Summary for the Busy Executive: Stylin' in church.

Disseminated throughout Europe by Dutch publishers, Vivaldi's instrumental concerti stood among the most popular and influential works of their time. If nothing else, they influenced Bach. Even today, Vivaldi's "Four Seasons" (part of the larger collection, Il cimento) remain bona fide classical hits, arranged and crossing over nine ways from Sunday. His vocal music – mainly his sacred works and his operas – have only begun to make their way. The Gloria in D, of course, is an exception – in fact, another hit – but even that took centuries to come out of the shadows. A large part of this obscurity arose from the fact that almost none of the manuscripts was published. Only recently has the rest of the vocal music begun to appear on the radar of the classical-music audience, in large part, I believe, due to the compact disc. Hyperion has inaugurated a series of Vivaldi's sacred music, of which this is the first volume.

Those who like the Gloria in D will probably like these works as well. All of Vivaldi's virtues as well as his limitations reveal themselves here. You will find neither the monumental spiritual drama of Bach nor the fine Georgian swagger of Handel. Instead, Vivaldi works, in Jane Austen's phrase, his "square inch of ivory," filling it with bold, imaginative strokes, as in Il cimento or La stravaganza, nevertheless in proportion to the canvas. On the other hand, these works brim full of what Beethoven, speaking of Handel, called "bold strokes." Vivaldi, one of the great orchestrators, varies his forces with each score: in the Magnificat, SSAT soloists (2 sopranos, alto, tenor, and no bass, as opposed to the usual solo voice or SATB), choir, strings, and 2 oboes; in Lauda, Jerusalem, SS soli, choir, and double string orchestra; in the Kyrie, double choir and double orchestra; in Dixit Dominus, a downright luxurious SSATB soloists, double choir, double orchestra, 2 oboes, and two trumpets. And that's just the orchestration, handled absolutely idiomatically, without even the whiff of a stunt.

Less than a quarter-hour long, Vivaldi's mini-Magnificat is crammed with good things. It begins with a solemn chromatic choral for the choir and moves to the "Et exsultavit." Vivaldi sets it up as a passage for successive soloists, but on the words "beatam me dicent omnes generations" (all generations shall call me blessed), specifically at omnes (all), the full choir mightily interjects, just in case you might have missed the point. The "Et misericordiae" works with the same chromatic idea as the "Et in terra pax" section of the composer's "famous" Gloria. At "Fecit potentiam" (he has shown strength), the entire ensemble astonishes with a unison entry – more felicitous word-painting. "Dispersit superbos" (he has scattered the proud) has the choir scattering the single word dispersit among the different sections, much like Bach did later in his Magnificat. I doubt this either an influence or a steal, since Vivaldi's sacred music confined itself mostly to the Italian churches and church institutions it was written for. The "Gloria Patri" more or less repeats the chromatics of the first movement, probably picking up on the words "Sicut erat in principio" (as it was in the beginning), a compositional trope of the Baroque era. You find it in Bach's Magnificat and in other scores as well. Vivaldi caps off the work with a Amen double fugue, so neatly and naturally brought off, you may not realize at first that it is indeed a double fugue.

Lauda, Jerusalem (praise, O Jerusalem) unfolds in one longish movement. Vivaldi structures the score much as he does his concerti – full ensembles with repeating material (called ritornelli) separating lighter solo passages made of freely-conceived episodes. The most arresting ensemble feature is, of course, the double choir, orchestras, and soprano soloists, and Vivaldi tends to handle them antiphonally overlapping one another, bringing the larger forces together for cadences. The composer injects variety into his ritornelli with electrifying declamation, the highpoints of which occur at "Emittet verbum suum, et liquefacies ea," telling how God sends out his word and melts the frost, snow, and ice, and at the final "et in saecula saeculorum. Amen" (forever and ever, Amen) which brings the psalm to an exciting finish.

The two mass movements, Kyrie and Credo, belong to two separate works, both Glorias. The Kyrie introduces a lost score (of which an "introduction" survives), and the Credo follows Vivaldi's less well-known Gloria in b. The composer divides the Kyrie into the usual three sections – Kyrie, Christe, Kyrie – with the Kyries for full choirs and the Christe for trebles only, thus providing the same sort of contrast that we hear in the Lauda, Jerusalem. The first Kyrie begins with a favorite chromatic idea that Vivaldi tended to recycle, if not repeat, in several scores. You hear a version of it in the opening to the Magnificat. It then moves to an idea based on arpeggiated chords. Most of the movement alternates between the two, but somehow Vivaldi ingeniously joins them just before the end. In the Christe, Vivaldi uses the trebles antiphonally. The final Kyrie is yet another wonderful double fugue for the combined choirs. One of its motifs is an ascending step-wise line that goes from the lowest to the highest parts, thus generating ever-increasing drama into the score.

Michael Talbot's liner notes point out that the Credo as Vivaldi's only choral multi-movement work minus solo voices. I've always regarded the Credo as a political document rather than as a poetic one and thus a challenge to achieving an expressive setting. Poulenc, for example, avoided the Credo altogether in his Mass in G. The high points for me are Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, which sounds like the march of Christendom, and Vaughan Williams's a cappella Mass in g, which teases out poetry and drama from unlikely sources. Most of the time, the composer's job becomes merely getting through all the talk of the Credo (and there's a lot of it) in good time, and the notes become attractive pegs on which to hang syllables. The opening section does just that, although Vivaldi's genius for exciting rhythmic declamation makes it something more. The "Et incarnatus" section is a chorale which resorts to one of Vivaldi's favorite chromatic tropes, similar to the opening of his "Winter" concerto from The Four Seasons.

However, Talbot rightly calls the "Crucifixus" "the jewel of the work." In fact, I think it one of the most remarkable movements in all of Vivaldi (that is, in the Vivaldi I know) – vocal, choral, or instrumental. Its "even, detached notes in the bass" depict "the slow walk to Calvary." This is chromatic music, but outside Vivaldi's usual habits. More accurately, I think, one would characterize it as genius harmonic progressions, absolutely unexpected, and yet not bizarre. Ascending and descending chromatic lines in the choral parts depict the agony ("passus") on the cross and the burial ("et sepultus est") of Jesus. The final section returns mainly to the declamation of the first, but concludes with another fugato on "et vitam venturi saeculi" (the life of the world to come).

Dixit Dominus always struck me as incredibly bloodthirsty, a war Psalm (110 or 109 if you're Catholic) all about God slicing through your enemies for you (or with you). Handel wrote my favorite setting, but Vivaldi doesn't lag far behind. In many ways, we've heard it all before – the antiphony between the double choirs and orchestras, the sudden unisons, the chromatics – but here Vivaldi elaborates. At "Tu es sacerdos" (thou art a priest), Vivaldi gives us not a fugue, not a double fugue, but a triple fugue (ie, a fugue with three subjects, any one of which can serve as a bass line to the other two) and a neat bit of word painting. As violins are throwing off crackling squibs, one vocal part sings in long notes the words "in aeternum" (forever). Vivaldi spotlights the two trumpets without accompaniment in the "Iudicabit in nationibus" (he will judge among the nations), turning them into the Last Trumpets and exploiting their range, top to bottom. As in the Magnificat, the "Gloria Patri" repeats the opening material, and for the same reason. Talbot considers the fugue on "Sicut erat in principio" the most elaborate Vivaldi wrote. It certainly juggles a lot of stuff, including an 8-bar subject that happens to be the same bass line Bach used in his Goldberg Variations. Apparently, like the "Dresden Amen," this was also a popular thematic bit for Baroque composers.

This disc inaugurated Hyperion's series of Vivaldi's complete sacred music with Robert King and the King's Consort, which I believe has been completed. As far as I'm concerned, it moves to the front of the line, despite such star competition as McGegan, Muti, Marriner, and even as far back as Negri. One can point to individual players and singers, but what really stand out are the exquisite balance among the forces, the elegant yet vital rhythmic drive, and the gorgeous tone. Furthermore, the disc is just plain fun, a real joy. I give it the Royal Schwartz Seal of Approval.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz