The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Barber Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

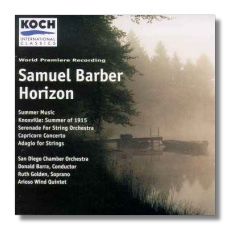

Samuel Barber

- Horizon

- Summer Music for Woodwind Quintet

- Knoxville: Summer of 1915 for Soprano and Orchestra

- Serenade for String Orchestra, Op. 1

- Capricorn Concerto for Flute, Oboe, Trumpet, and Orchestra

- Adagio for Strings

Ruth Golden, soprano

Linda Lukas, flute

Peggy Michel, oboe

John Wilds, trumpet

Arioso Wind Quintet

San Diego Chamber Orchestra/Donald Barra

Koch International Classics 3-7206-2 H1

The future business has its risks. In 1981, when Barber died, his music, with the exception of the ubiquitous and apparently unkillable Adagio, was seldom played or even recorded. Roughly thirty years of prestigious commissions and public acclaim came to an end in the 60s – in fact, with the Piano Concerto and Andromache's Farewell, both of 1962. We find several reasons for the neglect, but most agree that the precipitant cause was the disastrous première of the opera Antony and Cleopatra (1964) at the opening of the new Met at Lincoln Center. It was a high-profile failure and gave the New Music zealots an opportunity to trash the composer as not only old-fashioned but, worse, washed-up. They declared Barber's music irrelevant to the Zeitgeist (whatever that may mean) and post-Webernian serialism as the one true path.

The tonal vs. the serial argument turned out to be itself irrelevant, much like the Wagner vs. Brahms controversies of the late 19th century. Quite simply, music moved another way. It turned out that composers realized that in the 20th century, all centuries are contemporary. In large part, this is due to the technologies of radio and home music systems. A person can put in his 5-CD changer a Weelkes motet, a Hummel concerto, Aretha Franklin, Ein deutsches Requiem, and Maw's Odyssey. We may become cultural magpies, which has its own dangers, but neither the tonal nor the serial hegemony and New Jerusalem waits just around the corner. Today, most composers view the serial method as another technique in the artistic arsenal, rather than as a tenet of religious faith or heresy or as sign of artistic quality or lack thereof. In fact, reading over the polemics of the 50s through the late 60s, I invariably think how silly it all was.

In the meantime, people had to fight for Barber, as stupid as that now sounds. Since the late 80s, concert management and especially recording companies have made his work available. A recording from the Spoleto Festival of the revised Antony and Cleopatra made it quite clear that whatever the problems of the original production, the music didn't cause them. It contains some of Barber's most beautiful, powerful, and – dare I say it – advanced music. For Barber indeed wrote modern music. In fact, how could he help it?

Yet, for some reason, the critics had acted as if they were being fobbed off with marked-down Delibes. They hated what the public loved: a lyricism that fought for and won a listener's soul. In a way, both critics and public missed much of the point of Barber. He wasn't just a lyricist, but a composer who had mastered technique to such an extent, he could afford not to think about it consciously. He shows an imaginative approach to form, elegant even ruthless in its concision, and an ability to expand his range and technique without losing his individual profile. The Barber lyricism was something absolutely new in music, and I can trace it as early as the cantabile theme of the Overture to the School for Scandal. It seems to have belonged only to him and, as far as I can tell, has not survived through transplant to any other composer. An original voice may not be everything, but it is indeed quite a lot. At a time when "internationally-minded" composers all seemed to be writing the same piece, Barber sounded increasingly like the artist of integrity he always was, and people began to value him for it. When Perlman and Ma record his works for major labels, it's safe to say the composer has arrived.

Koch has led the way in new recordings of Barber, often going into obscure corners and becoming especially valuable in filling in the picture of Barber with performances of the late work. This CD programs old favorites (including Koch's second recording of the Adagio) as well as a CD première, Horizon.

Barber wrote Horizon for "The Standard Oil Hour" NBC radio program. He never published it (definitely his decision; G. Schirmer in those days would have printed anything he gave them, including a driver's license). The work lasts slightly over four minutes, and it interests Barber headbangers like me as the first cut at the wind quintet Summer Music, a staple of the wind repertoire. Summer Music had a fairly unusual genesis, which you can read all about in the liner notes. It's a gracious, elegant work, with some unusual features of construction, none of which get in the way of a listener's enjoyment. For half of its length, it's a chiasmic, "mirror" structure. There are four different ideas and sections:

- An introductory section, A

- A cantabile section, B

- A "martial" section, C

- A prestissimo, "bat out of hell" section, D, which is the pivot of the symmetry. From there on, the first three sections appear in reverse order

Thus, the structure of the first half is ABCDCBA.

The second half alternates A with apparently two new ideas, but these I believe come from section C and subsidiary material in A. Barber writes pretty tightly, but, more to the point, he writes something truly evocative in a medium more often known for its wit than its heart. There's a real longing in the piece, for what I don't know. But it very often reminds me of the line "Summer is gone; summer is ended." Perhaps it's for an unrecoverable past, a sentiment often expressed in Barber's vocal music. The Arioso Wind Quintet does a superb job not only with conveying the melancholy underlying the work, but also with letting loose in the riff-like passages.

The Serenade and Dover Beach (opp. 1 and 3 respectively) are the only two works in Barber's published catalogue that might have come from the 19th century. However, both are fairly early, and the Serenade at least was probably written under the eye of Barber's teacher, Rosario Scalero, a composer apparently passed by the times. By opus 5, Barber had definitely moved on. Still, it's a charming work which doesn't outstay its welcome. The performance here is good, but I prefer Schwarz on Nonesuch (79002-2).

The Capricorn Concerto belongs to Barber's attempt to expand his harmonic and melodic language during the 40s. He finds in Stravinsky's (and, here and there, Copland's) neo-classicism obvious inspiration, although we should point out that the tendency to concision and to making every note count was already part of Barber's makeup. Thus, the first movement contains a fugue that could have come from the Symphony of Psalms. The last movement echoes parts of L'Histoire du Soldat and Dumbarton Oaks Concerto. Yet, by the second movement, he can't resist the urge to sing, which he does in his own, rather than in Stravinsky's, way. Still, the texture lacks the opulence even of the recent Second Essay. At any rate, Barber quickly assimilates the Stravinsky influence and finds his own voice again in other works – in fact, by his very next work, the Cello Concerto. Still, the Capricorn Concerto is a highpoint of American neo-classicism, and, if Barber never repeated it, he managed to incorporate it into his own aesthetic. Barra and his soloists give a very lively performance. The soloists, in particular, inflect the music in a personal way, almost like jazz musicians, in strong contrast to the generic playing one normally hears in this work.

I suppose Knoxville: Summer of 1915 has become a Barber hit. I count six versions in my copy of Schwann's, including those by the highly-visible Upshaw and McNair. How times have changed. I remember when you could choose only between Steber and Price. For me, Steber remains definitive, but I haven't heard McNair. Upshaw's sold a lot of CDs, but I'm not wild about her version. It's not terrible. I just get the feeling that she doesn't understand the poem. She keeps reminding me of a dutiful, though talented voice student. There's an unwillingness or inability to commit herself to the passion in Agee's text, a meditation on "the sorrow of being on this earth," as – not its glories – but the ordinary things pass away forever. Steber's diction rates only slightly better than Sutherland's, but she definitely puts out the volts. She overwhelmed me from the first over 30 years ago, even though I couldn't understand her two-thirds of the time. I finally bought Agee's A Death in the Family so I could follow along. Ruth Golden, the soprano on this CD, to me is a well-kept secret. She may not have the pipes of Upshaw, McNair, or Price, but she's got real brains. She sings, not merely to produce pleasant sounds, but to intensify the meaning of the text. She is a superb Lieder singer. I have her in a Vaughan Williams recital (Koch 3-7168-2H1) and in Rodrigo's Cuatro Madrigales Amatorios (Koch 3-7160-2H1), and both are superb. This performance is no fluke.

I may be wrong, but I believe this is the first recording with the chamber orchestra forces of Barber's final revision. Like Copland in the Sextet or the original Appalachian Spring, Barber could make few sound like many. For me, he comes close to the perfect song, and he makes you believe he is simply singing. Agee's prose, magnificent as it is, would afflict most composers with nightmares of trying to come up with a musical structure that could carry the meaning and affect of the poem and retain a musical logic. According to Barbara Heyman, author of a fine critical study of the composer, Barber sweated blood over shaping the text, and even after its première kept tinkering with it. I think he does nothing less than triumph.

With the Adagio for Strings, we leave the realm of musical criticism for that of iconography. It's one of those rarities – like Mozart's Figaro Overture or Vaughan Williams' Tallis Fantasia – that resist criticism. You can analyze till your eyes cross and never get at what makes these pieces work. The Adagio has several versions – string quartet, organ, a cappella choir, full string orchestra, and chamber string orchestra. Of these, when it's played as a separate movement, I prefer as big a string sound as possible. My favorite recording remains Schippers conducting the New York Philharmonic, with massive climaxes that go through you (the whole LP is a classic; when will Sony reissue this on CD?). Still, Barra manages something fine with his chamber players. It's not my ideal Adagio, but it's very sensitively shaped and played.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz