The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Martin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

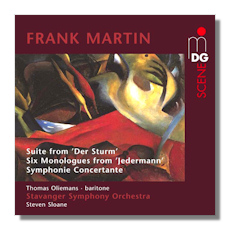

Frank Martin

Orchestral Works

- Suite from "Der Sturm"

- 6 Monologues from "Jedermann"

- Symphonie Concertante

Thomas Oliemans, baritone

Stavanger Symphony Orchestra/Steven Sloane

Dabringhaus & Grimm MDG9011614-6 61m Hybrid Multichannel SACD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Rites.

Swiss composer Frank Martin (pronounced Frahnk Mar-TAN) came to composition relatively late and even then learned mainly on his own. He began as a rather odd mix. He lived in Genève, as part of a Francophone culture, but within a musical environment that looked to Germany – in a sense, a kind of César Franck. Indeed, he once named Bach and Franck as his favorite composers. He had to work to accept Debussy and Ravel. Intellectually restless, he changed styles so many times that he resists pigeonholing. Bach, however, remains a strong influence in his work, but Schoenberg came to intrigue him. While never a strict serialist or even atonalist, he nevertheless adopted many of Schoenberg's ideas, as did some other tonal composers without abandoning tonality – John Adams, Richard Yardumian, Leonard Bernstein, Ben Weber, Kenneth Leighton, Olivier Messaien, Bernard Stevens, William Alwyn, and Benjamin Britten, to name only a few. Nevertheless, despite all his musical wandering, his music seems all of a piece. In characteristic tone, I'd liken his music to the Arthur Honegger symphonies – stern, monumental, but emotionally cooler. Never a prolific composer, like Stravinsky he turned out works of impeccable craftsmanship. He amassed a catalogue of respectable size by living long enough and working diligently.

Martin loved writing for the stage, although, as we should expect, he held unconventional ideas of theater. He tended to emphasize ritual and thus was drawn to oratorio (In terra pax, Pilate, Golgotha, and others), mystery plays, and French classicism.

In 1952, Martin began writing his opera Der Sturm, based on The Tempest by Shakespeare, and finished it in 1955. Instead of taking Shakespeare for his libretto, he chose instead A. W. Schlegel's German translation, in the composer's opinion a monument of German literature. Not that he didn't know enough English, for he had set five of Ariel's songs for a cappella choir in 1953 using the original texts – a touchstone of the choral repertory. The suite from the opera includes the overture and three of Prospero's speeches, sung by a baritone. The austere reserve of the suite struck me first. The overture depicts a tempest and its calm aftermath, but at a distance, if one compares it to Wagner's Flying Dutchman overture. Similarly, Prospero seems more a shamanist ritual mask than a flesh-and-blood duke (and father) who knows magic, especially beside Thomas Adés's portrait in his own Tempest opera or even Ralph Vaughan Williams's setting of Prospero's "The cloud-capp'd towers." I don't call Martin's approach wrong, merely different, given the subject matter – extremely anti-Romantic and anti-display.

The Six Monologues from Jedermann, also for baritone, set passages from Hugo von Hofmannsthal's adaptation of the Middle English play Everyman. Again, Martin emphasizes ritual. This is, after all, Everyman, not somebody with a driver's license. In Hofmannsthal's version, Death summons Everyman to appear before God to account for his life. He summons his servants to pack up all his gold. However, he finally realizes that he has pursued only money, and that cannot save him. He sees his life as worthless and not worth saving, which of course amounts to repentance and thus an appeal for salvation. It's not a lot of laughs (neither is the original), and the music would fit a particularly stern sermon – not fire-and-brimstone, but the cold burn of ice.

Martin wrote the Symphonie concertante for Twentieth-Century patron and conductor Paul Sacher, who commissioned work from many of the first-rank Modern composers, including a few of the big guns: Stravinsky, Hindemith, Bartók, Milhaud, and Martinů, as well as Martin. Sacher led not a symphony orchestra, but a large chamber ensemble, and Martin composed his score to suit. Originally, he orchestrated it for double-string ensemble, harp, harpsichord, and piano (in this form, called the Petite symphonie concertante). Later he scored it for full orchestra, the version we have here. I prefer the original because the original layout brings the architecture to the fore and because the sounds just interest me more. We have the strings bowed, struck, and plucked and the tonal ambiguities of the "continuo" instruments. The later full orchestration smoothes everything out and gives us, relatively speaking, a wad of sound.

In two movements, the form of each is both unusual and strong. The first movement resembles a passacaglia, but at two different speeds: a grave, stately introduction followed by an allegro, which takes the bass of the intro as its main idea. The second movement divides almost in half: an eloquent cantabile slow movement and a sprightly march on the main theme of the cantabile. The march builds in energy until the main idea becomes an heroic fanfare, and the piece concludes with a brilliant finish. This work has become, in both versions, one of Martin's most often played, and one can easily see why. High energy, both in rhythm and in color, and a rhetorical command that grabs a listener by the lapels.

The classic recording of both Der Sturm Suite and the Jedermann monologues comes from the composer himself with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as soloist, that of the Petite symphonie concertante either Ernest Ansermet or Leopold Stokowski. As far as I can tell, Sloane's recording of the full orchestration currently competes only with Matthias Bamert on Chandos. Fischer-Dieskau outshines baritone Thomas Oliemans, who nevertheless sings well in a Fischer-Dieskau light baritone. Bamert and Sloane come up about even as far as technical considerations go, although I think Sloane's reading ultimately more compelling. Still I don't sneeze at Bamert and can well imagine someone preferring his account. The MDG sound is superior.

Copyright © 2015, Steve Schwartz