The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, Lord Berners

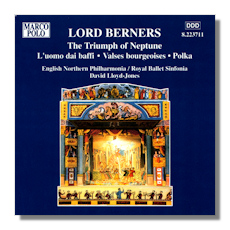

The Triumph of Neptune

- The Triumph of Neptune

- L'uomo dai baffi

- Valses bourgeoises (orch. Lane) *

- Polka* (orch. Lane)

Clive Bayley, bass

English Northern Philharmonia/David Lloyd-Jones

* Royal Ballet Sinfonia/David Lloyd-Jones

Marco Polo 8.223711 69:26

Summary for the Busy Executive: Fun and games.

One of the great eccentrics in music – so you can imagine just how loony he was – Lord Berners unfortunately survives as a character, rather than as a composer. He kept a specially-made piano in his Rolls-Royce, dyed the pigeons on his estate all sorts of surprising colors, and was famously ugly and a wit. It was he who said, "I am a quarter of an hour behind the handsomest man in Europe." Unfortunately for his reputation, he was also a serious artist in several media. He wrote, painted, and composed, all with distinction. He was the patron behind Walton and the Sitwells. Before he came into his money (and his title), he traveled extensively on the Continent as part of the British diplomatic service (a respectable calling for younger sons) and became involved with the Stravinsky-Diaghilev circles, both in Italy and in Paris. Most writers – although few have tackled this subject – tend to hail him as an antidote to the "insularity" of the British musical scene between the wars. However, the insularity charged to British composers largely doesn't exist (among the major composers at any rate) except as a polemical gambit by those who wanted to argue for certain postwar figures and could think of no other way. Vaughan Williams, Walton, Holst, Tippett, Britten, Berkeley, Brian, Rubbra – not to mention Arnold and Alwyn, among others – were all well aware of new musical currents. The really great ones simply tried not to imitate. If Vaughan Williams, for example, had been less "insular," he might have become Arthur Lourie or perhaps Alexandre Tansman.

Among the artistic movements of his time, Berners felt closest to dada and especially to surrealism. Writers have called him the English Satie, and Virgil Thomson considered him a brother. However, his music really has little to do with either Satie or Thomson, except that it's usually stripped down to essentials and modestly elegant in scope. This shouldn't surprise anyone. All three composers use simple means but remain strongly individual. Thomson's simplicity deliberately invokes the pioneer and the Great Plains as well as the formal strength of Cubism. Behind all of Satie's jokes stands a very solemn mystic. It's much harder to get a fix on Berners, mainly, I suspect, because his artistic personality lacks the strength of the other two and also because his musical output was much smaller. His music, although beautifully worked, has little point. It closes off rather than leads anywhere. Put it beside Walton's Facade or any of a number of works by Poulenc, and it tends to bleach out. And yet, it delights, perhaps the most important thing about it, with its own very individual harmonic sense. Berners also provided scores to a few films, most notably a really fine one for Cavalcanti's Nicholas Nickleby, although it's far more Romantic than his concert music.

Berners wrote The Triumph of Neptune for Diaghilev. He found his "themes" in the "penny-plain and tuppence-colored" postcards of the 19th century and in British pantomime. It counts as one of his longer works, and it contains one splendid joke – a spoof of "The Last Rose of Summer," sung by a gentleman in his bath. The CD advertises the complete score, and certainly contains more numbers than the usual suite (at one time available with Barry Wordsworth conducting on EMI). One would say more accurately that it presents all the numbers whose music has survived. Time has not been kind to Berners. Very few scholars have shown an interest in him, so it may take rather a long time for the ground to be thoroughly picked over. At any rate, enjoy wonderful tunes and infectious rhythms in the meantime.

L'uomo dai baffi (the man with the moustache) from 1918 sounds a bit more astringent, far closer to the "modern" music of its time, but also less individual than the Triumph, sharing certain tropes with Stravinsky's Pièces faciles. Still, Berners even at this time shows the concision and clarity that is his hallmark. He gets off a joke on Beethoven's Fifth, but it's rather isolated. Once he tells it, he does little with it other than repeat.

Philip Lane, the producer and sleeve-note writer for this CD, contributes two of his own orchestrations of some Berners four-hand piano music, as well as the "Polka" originally written for a Christmas pantomime. His orchestral sound captures the mixture of cheekiness and sendups of pomposity that Berners shows throughout Triumph, at any rate.

David Lloyd-Jones and the English Northern Philharmonia play with style and enjoyment, exactly what the music needs. The recorded sound has too much echo for my taste, but I can live with it.

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz