The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Johann Sebastian Bach

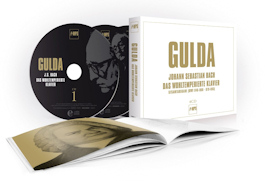

Das wohltemperierte Klavier, BWV 846-893

Friedrich Gulda, piano

MPS 0300650MSW 4CDs 283:55

Austrian Friedrich Gulda was born in 1930. Here from MPS is a four-CD set of his recordings of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier made in April 1972 and May 1973. Originally issued on five LPs (Philips Classics LP 412794-1) the obviously meticulously-remastered original tapes sound every bit as well as could be expected. BWV 846 to 872 occupy the first and most of the second CDs. The second Book (BWV 870-893) takes up the final six tracks of the second CD and all of the third and fourth CDs. It must count as one of the most searching, technically accomplished and overall satisfying recordings not on period instruments now available. At a bargain price, this is not a set to miss.

The first quality to strike listeners will be Gulda's poise. He plays with a grace, delicacy and discernment that gently but irresistibly pull us in to the music – as if we had to strain to catch every drop of gold from Bach's creation. There's nothing underplayed. Nothing too taut or too soft for comfort, of course. Rather, Gulda distills the relationship between melody (long, unfolding fronds of tune and extension matched perfectly with inevitable, self-contained cells of notes) and tonality: the harmonics of the keys which Das Wohltemperierte Klavier famously explores. We can easily take in even the extended passages (such as those towards the end of the BWV 866 (B flat Major) Prelude, Book 1, number 21 [CD.2 tr.11]) without having to compress Bach's design. Gulda makes the music his own – but only while it's "on loan" from Bach.

There is nothing weak, tentative or retreating in this approach. Listen, for instance, to the majesty which Gulda reveals in the BWV 853 (E flat minor) Prelude and Fugue, Book 1, number 8 [CD.1 tr.16]. Bach knows exactly where the music is going. He has total confidence, though, that any apparent digression – harmonic or melodic – is not primarily for contrast. Rather, it's there in order to contribute to our experience and understanding. Gulda is perfectly in accord with this; he never suggests that progression through the music is anything other than inevitable. But it's equally infused with life, with spontaneity and vitality – one of this interpretation's greatest achievements. The onset of the conclusion of the BWV 855 (E minor Prelude) and transition to its fugue, Book 1, number 10 [CD.1 tr.s19, 20] is a good example of this mix of control and exuberance. We're at first surprised by the slight change in dynamic and tempo. But the playing seems to be in the only way possible, and of the only music possible.

Gulda must have felt that Bach needed no extra dramatics, no gimmicks, no imposition of a player's personality or even exposition of pianistic skills. The notes were enough. We are in his debt for this. The result is that we feel drawn to keep returning to the music time and again in order to deepen a response to its essence. There is very little surface; nor anything superficial.

Gulda always evokes a reaction from the listener. Maybe it's because so many of these short works (at eight-and-a-half minutes BWV 869 (the B minor fugue, Book 1, number 24) is the longest) are played as though the pianist were discovering the music himself for the first time. This is a risk: each prelude and fugue relies on two attributes for color and impact. Firstly, on superb technique. Secondly on the performer's conception of structure – both internally and in relation to (all) the other preludes and fugues – particularly harmonically. Gulda provides both of these in plenty.

At the same time, though, nothing must be overdriven or become purely mathematical or mechanical. Gulda does not fail here, either. There is depth, richness, breadth and emotion. His is not a romantic interpretation; for there is precision and focus as well as nuance. He seems to "claim" each work and offer it to us from a position of fondness, closeness to Bach, and belief in the composer's monumental achievement.

Gulda's favorite composer was Mozart. Indeed the pianist said that he wished to die on the birthday of Mozart (January 27). So he did: in 2000. These performances of Bach's music are in some ways played as Gulda played Mozart. He brings a beguiling simplicity which barely conceals infinite complexity. Such depth is always transparent, though. It conveys simultaneously the open-endedness and yet the finality of such great profundity as Bach offers in his melodies and counterpoint. To this Gulda adds a crystalline lightness; a faith that there is always something beyond the music. It's in many ways an ideal balance.

Gulda recorded each Book of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier in a single session; and over a year apart. In fact there is a distinct tonal difference of the piano's sound between Books I and II, the latter sounding less "ethereal". This is no detriment: in each case Gulda was enthusiastic about the MPS studios. He felt that their absence of resonance, the microphone placing which he asked for (directly above the Steinway's strings) and this option to accentuate the integrity across each set of 24 had its own strengths. After more than 40 years we can say that he was right. This is a splendid performance and one which all lovers of Bach will want to own and come to know, no matter how many other interpretations they have.

The acoustic of the MPS studio, then, in the relatively small city of Villingen, in the Schwarzwald-Baar district of southern Baden-Württemberg in Germany, is dry, and contained. Rightly, it's not one pressed into serving spectacle and overtly conscious performances. At the same time, the remastering does everything appropriate to emphasize the intimacy and intensity of the music – and of this interpretation in particular. The piano is very close; every note, even the sense of some "mechanics", can be heard clearly and with the immediacy needed. It should be said that there are a very few places on CD 3, e.g. tracks 7 and 8, where a "tinniness" is perceptible. Barely – but enough to remind us that these are 40+ year-old tapes. Various of those responsible for and/or involved in the performance and production – including Gulda himself – contribute to an illuminating set of short essays in the bound in booklet. This is a classic set of performances which is warmly recommended in every way.

Copyright © 2015, Mark Sealey