The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- D. Scarlatti Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

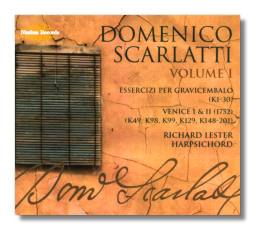

Domenico Scarlatti

Complete Sonatas Volume 1

- Essercizi per Gravicembalo K 1-30

- Venice I & II (1752)

- Sonata K 49

- Sonata K 98

- Sonata K 99

- Sonata K 129

- 53 Sonatas K 148-201

Richard Lester, harpsichord

Nimbus NI1725

'Domenico Scarlatti was without doubt the most original keyboard composer of his time.' So wrote Ralph Kirkpatrick, Scarlatti's biographer and cataloguer of his works. Born in Naples in 1685 – like Handel and Bach – Scarlatti developed comparatively late as a composer… on his appointment as chapel music master to the Portuguese royal family, specifically as teacher to the nine-year-old daughter of King João V, Maria Barbara. When she and her family moved – to Seville on her marriage; northward to Madrid; elsewhere in Spain on royal 'progresses' – so did Scarlatti.

It was in Andalusia that the Italian composer was able to hear and absorb the rhythms and color of Flamenco, folk music and the tunes of what Charles Burney called 'carriers, muleteers and common people'. Although we don't know very much more about Scarlatti's life in Spain, except that he was married twice and had nine children, it's thought that he wrote the majority of his magnificent keyboard sonatas late – between 1738 and 1756. These constituted fifteen volumes of thirty sonatas each… Volume X has four extra, so they amount to over 550 in all.

On Scarlatti's death in 1757 the by now Queen Maria Barbara bequeathed the bound volumes to the castrato Farinelli; some time after the death of the latter in 1782 they came to be housed in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice. Thereafter referred to as the 'Venice manuscripts', these are the chief source for this recording. It's how the volume names of this splendid Nimbus set are 'Venice I', 'Venice II' etc.

What will make this series by Richard Lester the first (and currently the only) truly complete recording of Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas is the inclusion in Volume 7 of works extra to the heretofore accepted fifteen-Volume corpus, works authenticated by W. Dean Sutcliffe, author of The Keyboard Works of Domenico Scarlatti; he also supplied some manuscripts. Such manuscripts in Scarlatti's own hand are rare. Lester also points out that, although the Kirkpatrick numbers are used throughout this project, the chronology of the sets follows Maria Barbara's manuscripts.

Lester also used Maria Barbara's detailed inventory of the instruments (seven harpsichords and five pianofortes, of which two were converted into harpsichords) in her possession: they were presumably well-suited to her tutor's compositions. There is a puzzle, though: none of them had a compass of more than 56 keys whereas many of Scarlatti's sonatas demand a full five-octave range. Two instruments are actually used in this set. They are copies – by Michael Cole of Cheltenham, Gloucestershire (UK) – of a 1785 instrument by the Portuguese maker, Joachim José; and of a two-manual English harpsichord, by Stephen Wessell.

This first volume consists of six CDs, Kirkpatricks 1 – 30; 49, 98, 99, 129; and 148 through 201. Ninety pieces in all. It might at first seem daunting to think of almost 6½ hours of what – to the uninitiated – could be a little foolishly dismissed as similar-sounding harpsichord music. But just sit down and listen! Each sonata has its own little (some not so little) world; its own palette of bright and deep colors; its own internal logic shot through with now subtle, now insistent rhythm; its own beauty, challenges and satisfying sound picture. The Essercizi (K1 – 30) act as an introduction to the rest of the opus, but are in no way inferior to the other sonatas; all have this variety, one from the next.

This is not to say that all the sonatas are purely, or even principally, figurative; though some are. Dance, however, is everywhere – almost everywhere; the spirit and the letter of a whole host of dances. From almost the first few (K5, K6, K10, K15, K17, K26 and K28) sonatas the rough, exuberant rhythms and harmonics of the fandango hold the listener in their grip. K17 and K26 even sound like the very Iberian taconeo (heel stamping); listen too to K160, K161, K167 and Ks169 through 174 for clear dance influences. Similarly, such sonatas as K9 and K25 are redolent of the melancholic, as heard often in Spanish folk song. To listen to one after another is to appreciate the genius of Scarlatti in evoking so much in such a short time (few of these sonatas are more than five minutes long); never overplaying the drama, sophisticated tonality or melodic inventiveness; and yet conveying great beauty very persuasively.

Other sonatas in the late K150s (K157 in particular) are examples of ways in which Scarlatti superimposes one rhythm on another with dramatic and satisfying effect. This is more complex than classical dance and repays careful attention. By CDs 5 and 6 the degree of technical difficulty has increased: significant virtuosity is required – Lester has it in reserve – and has the great judgement as well to make the most of the odd surprises (K49 and K191, for example) without the result being showy or self-conscious. And one way of appreciating this is indeed to sit down and work your way through several (all?) CDs at once. Then the richness of the sheer variety and inventiveness is evident. The way in which Lester adapts his approach and execution to the atmosphere of each sonata and group of sonatas is inspiring; he never looks for artificial decoration, or forced emotiveness. His style and execution are relaxed and natural, yet full of energy – all in exactly the right amounts. This is no mean achievement. Indeed Lester's approach is that of someone who both loves and is still in awe of this music. That's not to say it's 'unfinished' playing; rather, that he presents each sonata to us as a study in freshness and enthusiasm… both his and Scarlatti's. It really is the most pleasing playing and could make or break the whole experience. It makes it.

Richard Lester's reputation is to some extent also being made by this massive project. Among his teachers were Bernard Roberts and George Malcolm; it was at Dartington Summer School that Lester's enthusiasm for the Scarlatti sonatas was sparked, by Valenti, and an earlier single volume from the same repertoire was released to great critical acclaim. Contributing to various publications in the area and holding several academic and performance positions in the United Kingdom, Lester's accomplishment with this huge undertaking for Nimbus seems likely to be his point of no return. It's a joy to observe.

Other competitor Scarlatti keyboard sonata series are that by Scott Ross, which is truly one of a kind, though over 20 years old now; it's superb and broke a lot of new ground at the time. The CD-by-CD series by Ottavio Dantone on Stradivarius has much to recommend it. Then there is the Naxos one disc at a a time series using different pianists: debate rages as to whether the piano is really an acceptable alternative to the harpsichord. Given the color and timbre of the latter alone, it's easy to say that the harpsichord 'has it'! After listening to the vigor, excitement yet meticulous detail with which Richard Lester plays in this first volume of this Nimbus series, he too (and his series) appear to 'have it' – wholeheartedly recommended.

Copyright © 2007, Mark Sealey