The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Vaughan Williams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

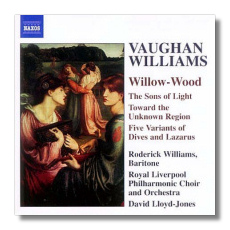

Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Toward the Unknown Region (Song for Chorus & Orchestra)

- Willow-Wood (Cantata for Baritone & Orchestra)

- The Voice out of the Whirlwind (Motet for Chorus & Orchestra)

- Five Variants of Dives & Lazarus for Strings & Harp

- The Sons of Light (Cantata for Chorus & Orchestra)

Roderick Williams, baritone

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra & Choir/David Lloyd-Jones

Naxos 8.557798 61:51

Summary for the Busy Executive: Where have these works been all your life?

Willow-Wood, a cantata on poems by D. G. Rossetti, provides the big news here, as it receives its first recording. It is probably also very close to its first modern performances since the 1909 orchestral première. For Vaughan Williams headbangers like me, the issuance, editing, and publication of the composer's pre-Ravel music constitutes a cause for celebration. We get a fuller picture both of the composer's artistic journey and of his range.

Vaughan Williams had a stern conscience. He ruthlessly suppressed early works he thought "uncharacteristic" of him. He inherited the criterion "characteristic" from his beloved teacher Parry. For both, it took on an ethical connotation, an aesthetic equivalent of the Socratic "Know thyself." He also tended to lose interest in work he had already written, reserving his enthusiasm for his current projects. Still, his manuscripts, including the early ones still extant, found their way to the British Museum, and lately, with the approval of the composer's widow, the amazing Ursula Vaughan Williams, they have undergone scholarly editing, performance, and recording. Hyperion's two-CD set of "The Early Chamber Music" proved that many of these works, far from the stumbles you might have expected, actually proved not only fully professional, but powerful in their own right. Their only fault is that they don't sound like the Vaughan Williams who finally emerged from his apprenticeship.

Willow-Wood comes originally from 1903, a version for baritone and piano. He later orchestrated it and added a women's chorus. Then, despite some good reviews, he forgot about it until slightly before his death, close to half-a-century after its composition, when he (not too aggressively) tried to get a publisher for it. The cantata sets a sonnet sequence from Rossetti's House of Life, which the composer also went to for his 1903 song cycle of the same name. I've always felt that Vaughan Williams' choice of texts at this point in his career represented finding his way to his musical self. After all, neither Rossetti nor Whitman (or even the later Housman) were all that often set at the time. One might wonder what the composer thought he could get from them. I think it a fair bet that he, like Parry and Stanford before him, believed that if he could "crack" great poetry, he'd have necessarily written a great song. Of course, it's false reasoning, and a lot hangs on the "if." After all, Brahms wrote great songs to terrible texts, as did Schubert, Mussorgsky, and Mahler. Rossetti unleashed VW's passionate, sensuous side. To some extent, time has dated the passion, a bit too hot-house. But, if you like Bantock and Delius, you stand a good chance of going for this. With the exception of "Silent Noon," to me a great song by any reasonable standard you care to apply, I'm not fond of the House of Life cycle, but Willow-Wood seems to me a considerable improvement. Perhaps some re-composition accompanied the orchestration. To me, it's VW's Tristan – a reminder that the composer loved that opera so much, he couldn't sleep after hearing it for the first time. There's a Tristan-ish chromaticism about it (dressed up in Ravelian colors) that will probably surprise many of Vaughan Williams' admirers. The composer never did anything like it again, although you can see a kind of update in later works like Riders to the Sea and the Sinfonia Antartica.

Of the two early major poetic influences on VW, Whitman proved the more lasting. Toward the Unknown Region (1905-06), begun later than the Sea Symphony and finished sooner, is, as far as I know, the first major orchestral work the composer acknowledged. Ultimately, it derives from something like Brahms' Alt-Rhapsodie or Schicksalslied, or, more immediately, Parry's Blest Pair of Sirens. It pours forth one long song on rhythmically-tricky verses. Indeed, the span of the musical paragraphs impresses me the most. Vaughan Williams fashions musical cogency to Whitman's ramble without, furthermore, resorting to padding or forcing into conventional four- or five-line song structure. It contains much of the "atmosphere" of later Vaughan Williams: the march of the finale to the "London" Symphony, the opening of the Fifth, for example. It may well have been this piece that caused Stanford during a performance to turn to Parry and remark, "Big stuff, eh, Hubert?" Parry replied, "Yes. There's no doubt about him, thank goodness."

The 5 Variants comes from 1939, Vaughan Williams' contribution to the New York World's Fair (Bliss's Piano Concerto was another work which enjoyed a life beyond that occasion). It's not exactly variations, but riffs on five different folk variants of the tune "Dives and Lazarus," first collected by the indefatigable Cecil Sharp. Still, VW had known it previously (as a child, in fact) in a variant – the Christmas carol "Come all ye faithful Christians." The lines between variants and sections tend to blur, to give us a long meditation on the tune. For me, it's one of VW's best works, so full of craft that you forget about craft and concentrate on the psychic journey it takes you on. Vaughan Williams often got accused, particularly from the Fifties on, of taking the easy way out, of falling back on a manner, rather than rethinking his art. Anyone who thinks this a simple rewrite of In the Fen Country or the Tallis Fantasia simply isn't listening.

I heard the motet The Voice out of the Whirlwind in its original 1947 version for choir and organ. I didn't think much of it then. This did indeed strike me as a simple rewrite of part of his great ballet Job. My coolness could very likely have derived from the performance. The composer orchestrated the piece in 1951, the version here. In its orchestral dress, it's almost as overwhelming as the ballet.

The cantata The Sons of Light also comes from 1951. Vaughan Williams responded to a commission from the Schools Music Association. The composer, an enthusiast of amateur music-making, rightly judged the musical health of a country by its amateurs. He practiced what he preached. His own Leith Hill Festival brought together amateurs on a large scale. His experience with amateurs gave him a comprehensive sense of their capabilities. Consequently, he hardly ever sounds as if he writes down to their level. Only when you compare this work to something like the Sea Symphony or Dona nobis pacem do you get a sense of how much more difficult he could have made The Sons of Light. The score sets a remarkable text by Ursula Vaughan Williams which gracefully and wittily runs through Christian, Classical, and astrological myths of creation. The verse has an Auden-like polish. The composer must have rejoiced to get a text like this. I've never seen anything by his widow that wasn't astonishingly first-rate, but it's almost always been libretti for the composer. I've come across only her biography of the composer, but I'd love to read a book of her poetry or a novel, if she's got 'em.

Musically, the work anticipates VW's Christmas cantata Hodie of 1954, especially that work's "March of the Three Kings," with the composer's interest in new orchestral sounds, particularly from the tuned percussion. We even hear little shards of Willow-Wood, but in a much cleaner frame and a far more sophisticated context. I first heard the work on a Lyrita LP, which I don't believe the company ever re-issued on CD. I liked it then. I like it now. It may not be a major score – certainly it's not as ambitious as Hodie – but it's a solid one. Again, the long spans the composer builds, particularly in the first and second movements ("Darkness and Light," "The Song of the Zodiac"), impress me most and point to the considerable symphonist.

The performances, unfortunately, vary. Toward the Unknown Region gets a good reading, but it falls short of Boult's on EMI. The choir lets Lloyd-Jones down. The sopranos sound a little strident and young, and the blend and tone overall needs improvement. Roderick Williams, on the other hand, does beautifully as the soloist in Willow-Wood. He has a light, clear, flexible baritone, perfect for the subtle shadings of phrase the poetry and the music demand. The Variants, probably the best-known piece on the disc, get a fairly flat reading, unfortunately. The string tone is thin, and I miss the sweep of the music. Better you should go with Hickox, of the accounts currently available, on either EMI or Chandos. The different labels couple different things. If I prefer the EMI, it's because there's more really good "obscure" VW on the program. Best of all would be David Willcocks on an old EMI LP. I have no idea if it ever got transferred to compact disc. The Sons of Light comes off well, in a vigorous performance, I think as good, if not as suave, as Willcocks's account on Lyrita.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz